President al-Sisi promised, but has failed to deliver civilian rule, a healthy economy, an end to war, and protections of rights.

عربي

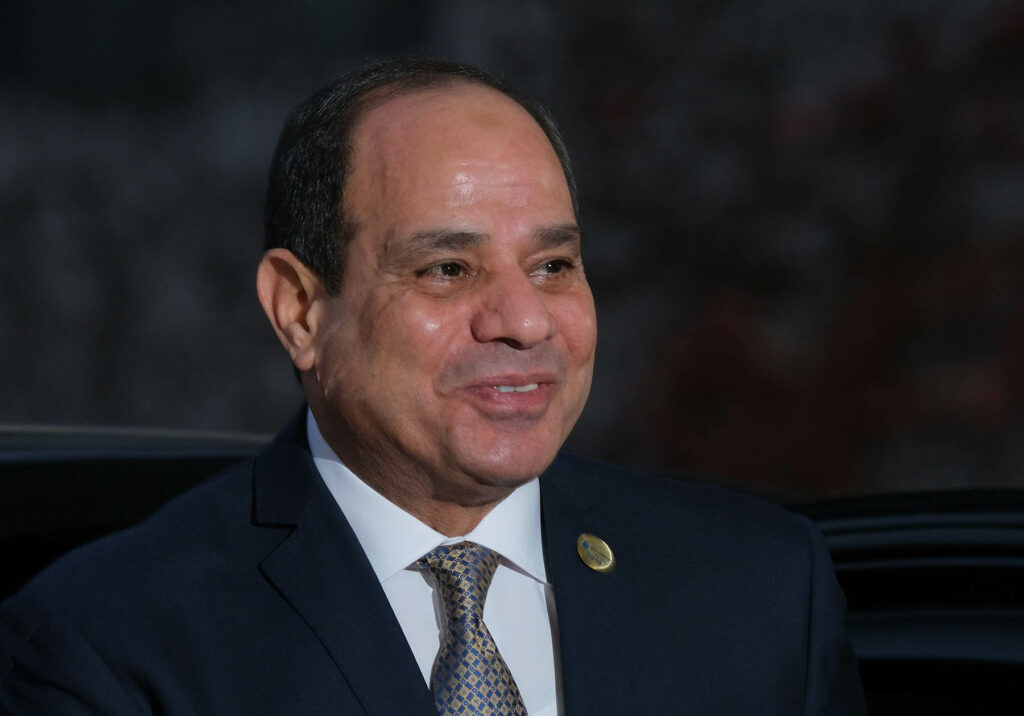

Eight years ago this month, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, then Defense Minister, announced the removal of the country's first elected president, Mohamed Morsi, and suspended the country's constitution.

Al-Sisi promised to ensure civilian rule with no military role in the government or the economy; a better quality of life for Egyptians; an end to the war in Sinai; and better freedoms and protections for all.

But a close look at Egypt eight years on shows a dark reality of broken promises, with Egyptians living under near total military control of their government and economy, seemingly endless war and destruction in Sinai, and unprecedented crackdowns on freedoms and civil society. Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN) has reviewed eight of President al-Sisi's commitments and evaluated his record eight years later.

- Unprecedented Military Control over Government, No Civilian Oversight

The military establishment has long propagated a narrative to legitimize its role as the only institution capable of ensuring stability and order, placing itself above other state institutions as the guardian of the constitution and political stability. Article 200 of Egypt's 2014 constitution states that the military safeguards the constitution and democracy, protecting the state, rights, and freedoms of individuals. Al-Sisi justified the 2013 military coup by arguing that the constitution gives the military the authority to remove President Morsi and to ban the Muslim Brotherhood because it threatened political stability and the constitutional order.

When al-Sisi overthrew Egypt's elected government, he promised not to run for president, and appointed a civilian, Adly Mansour, as interim president. He also assured Egyptians and the international community that Egypt would remain a civilian controlled country. However, on March 26, 2014, less than a year after removing Morsi, al-Sisi announced his candidacy for the presidency. Al-Sisi won the presidential election, setting the stage for an increased role for the military in Egyptian politics.

Rather than limiting the role of the military, al-Sisi has expanded its participation in all civilian public functions at the national and local levels, extending military control over every province in the country, and authorizing the military to carry out basic policing and judicial functions. He has relied on a rubber stamp parliament to approve numerous laws that have dramatically expanded the power of the military and provided immunity to its personnel.

Perhaps most notably, in July 2020, al-Sisi ratified a law amending the Popular Defense Law and the Military Education Law (Nos. 165/2020 and 46/1973) that mandates the Minister of Defense to appoint a military counselor in each province in Egypt to oversee and execute local public policies. The law also gives military counselors the right to attend a province's executive council meetings. Al-Sisi even suggested that the army should appoint an officer to each village in Egypt to oversee development efforts.

Despite its increased role in politics and governance, the military is now immune from any oversight or accountability by parliament or any other state institution. Further, civilian institutions have no control over the military's budget. The 2012 constitution granted the military full control over its budget without any parliamentary oversight, but the 2014 constitution went even further, requiring the National Defense Council to approve any discussion of military affairs by the parliament.

This lack of oversight continued in Egypt's 2019 constitution, as Article 203 does not allow any civilian body to review or approve the military budget. The details of how the army spends its budget and allocates its resources are not included in the public budget for parliamentary review. Only an aggregate total military budget is allowed to appear in public records.

Al-Sisi promised to save Egypt from perceived oppression under the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Morsi presidency, but he has legislated and implemented far worse oppression than any government in Egypt's modern history.

Al-Sisi has also immunized military officials from prosecution for crimes, including mass killings of protesters in 2013. In July 2018, parliament issued the law on the "Treatment of Senior Commanders of the Armed Forces" (No. 161/2018) granting high-ranking military personnel protection and diplomatic immunity against criminal prosecution, including international prosecution, related to any act they committed between July 3, 2013 and June 8, 2014.

The government passed this law in light of specific concerns of international actions to indict security forces involved in serious human rights abuses and crimes against humanity before and after al-Sisi's military coup, including the Rabaa massacre of 1,100 protesters, as well as other killings of protesters. Under Egyptian law, no legal investigation or judicial action can be taken against any military personnel unless the Supreme Council of Armed Forces, a military body, grants permission.

Likewise, in October 2014, al-Sisi issued an executive decree that places vital state facilities, such as electricity, gas, and oil facilities, railroads, roads, bridges, and universities, under military court jurisdiction for two years. Public prosecutors were directed to refer any crimes related to those facilities to military courts. The decree aimed to deter any protests, which had escalated after the ouster of Morsi. About 820 civilians were referred to a military prosecutor in two months after the issuance of the decree. It is unclear whether this law remains in effect.

Media outlets have been one of the primary targets that al-Sisi government officials have sought to control and use as propaganda for the government.

Source: Getty Images

In April and May 2020, taking advantage of the coronavirus pandemic, the House of Representatives passed amendments to Emergency Law (No. 162/1958), effectively extending all civilian policing functions to the military by mandating security and military personnel authority to execute the president's orders with the same rights and duties of judicial arrest officers, and authorizing military prosecutors to investigate crimes referred to it by military forces.

Military trials do not allow individuals to appeal court verdicts. Al-Sisi renewed the Emergency Law for the 17th time on July 12, 2021. The new extension began on July 23, 2021, suggesting that the misuse of this law will continue indefinitely.

- Al-Sisi and the Military Have Expanded Control over Egypt's Economy, with Vast Ownership of Businesses throughout the Country

Under al-Sisi, the military's ownership, power, and control over the economy has dramatically increased, leading to a hybrid economy with military personnel now largely managing and administering major state-run projects and reaping the public's profits. In December 2016, al-Sisi claimed that the military owned only two percent of Egypt's economy but in fact, no one knows its actual ownership, with estimates varying between 3% and 20%. The military oversees roughly a quarter of all government housing and public infrastructure spending of approximately 370 billion EGP (about $6 billion).

In September 2019, Colonel Tamer Al-Rifai, a former military spokesperson, said that the military is operating 2,300 projects employing about 5 million civilians. The military also has undertaken the direct distribution of affordable or no cost state-funded goods, such as food, thus enhancing its public perception as a charity provider. More recently, al-Sisi even urged companies owned by the military—itself a public entity owned by the Egyptian people—to enter the stock market "to give Egyptians the opportunity to own shares in them."

At the same time, the scale and power of the National Service Projects Organization (NSPO), the economic arm of Egypt's armed forces that owns and operates several infrastructure, construction, agriculture, food, and dairy projects, has greatly expanded, stifling private sector companies through unfair competition practices. Companies owned by the military are typically exempt from tax and customs duties, including value-added tax or customs on goods, equipment, machinery, services, and raw materials needed for armament or defense and national security.

Military companies, including the NSPO, are also exempt from public auditing and civilian oversight pursuant to amendments to the Government Contracting Law (No. 182/2018) passed by al-Sisi's government in 2018. Moreover, al-Sisi has issued a host of executive decrees granting the military privileged economic status, including allowing the Egyptian Armed Forces to establish for-profit economic enterprises on lands owned by the state and allocating land to the army in the New Capital under construction east of Cairo on the Cairo-Suez Road.

Moreover, al-Sisi granted himself full control of the Tahya Misr Fund (TMF), effectively a massive slush fund with reported assets of at least 8 billion EGP ($510 million) over which he has total control and to which major private business owners are "encouraged" and pressured to donate as a show of loyalty to the government. Al-Sisi established the TMF on July 1, 2014 with the stated goal of allowing the public to donate to public development projects to improve the country's socioeconomic conditions.

The Establishment of TMF Law (No. 84/2015) authorizes the Prime Minister to manage the fund, but allows the President to specify how and for what purposes its funds are used. Existing government regulations on the management and allocation of public funds are inapplicable to the TMF, and it is exempt from public accountability regulations.

On June 15, 2021, al-Sisi approved amendments to the TMF Law (No. 68/2021), which exempt the TMF from all current or future taxes, customs, or government fees. There is no transparency about who has donated to the fund, how much they have donated, how the funds are spent, or how they will be spent in the future.

- Al-Sisi has Grown the Economy for the Military, but the Egyptian People Remain Impoverished

President al-Sisi promised to save the Egyptian economy and even claimed an "economic miracle" under his rule, with the economic growth rate increasing to 5% annually between 2016 and 2019. (The growth rate fell to 3.5% in 2020 largely due to the COVID pandemic.)

However, most Egyptians have not enjoyed the benefits of this growth. Under al-Sisi's rule, the poverty rate of $3.20/day for lower-middle income countries has dramatically increased to 28.9% in 2018, up from 18.1% in 2015. A greater percentage of Egyptians, 3.8%, now live below the international poverty line of $1.90/day.

Instead of expanding the social safety net to include impoverished Egyptians, the government has implemented IMF-imposed austerity measures, including cutting fuel subsidies, limiting public sector wages, and devaluing the currency. In addition, the government imposed a flat value-added tax currently of 14%. Like all of these measures, this regressive tax places a disproportionate burden on Egypt's poor and middle classes.

The IMF program has not helped improve the quality of life in Egypt, nor has it helped address the country's national debt. The gross national debt as a share of GDP has increased, from 84% in 2013 to 90.2% in 2020. Some economic projections conclude that Egypt's national debt will reach $557.7 billion by 2026. In contrast, the country's GDP was only $363.1 billion in 2020. Moreover, since 2015, real wages in Egypt have witnessed a significant decrease each year: falling 1.7% in 2015, 2.8% in 2016, 9.8% in 2017, 13% in 2019, and 5.8% in 2020. While military and political elites remain largely insulated from these economic struggles, the Egyptian people do not, and it is becoming increasingly difficult for Egyptians to meet basic daily needs such as food and shelter.

- Al-Sisi Promised Enhanced Freedoms, But Expanded Restrictions on Civil Society

Al-Sisi promised to save Egypt from perceived oppression under the Muslim Brotherhood-affiliated Morsi presidency, but he has legislated and implemented far worse oppression than any government in Egypt's modern history. Al-Sisi claimed that the Muslim Brotherhood refused to abide by the constitution and govern lawfully, but he has issued draconian laws that eviscerate the rights guaranteed in the constitution, including renewing the country's emergency laws every three months since April 2017. The al-Sisi government also has committed serious violations of human rights, including wide-scale arrests, unjust prosecutions, torture, and extrajudicial killings throughout the country. Al-Sisi often justifies these acts as necessary to maintain order and stability, while in fact they have created an atmosphere of fear and political repression.

Al-Sisi used the security deterioration following the military coup against Morsi to issue several draconian executive orders and laws to control the public sphere. Transition authorities issued approximately 380 laws and executive orders in the absence of a sitting parliament between July 3, 2013 and January 2016. The constitution passed in 2014 required a new parliament to approve, amend, or annul these transitional laws and orders.

When the new parliament finally convened in January 2016, the Speaker of Parliament Ali Abdel Aal said that the lawmakers would review all 380 laws and executive orders within ten days. Ultimately, the parliament approved nearly all these laws and orders without review, even though many of these laws were controversial as they set new restrictions on citizen's basic rights and freedoms, and gave the president more powers.

In August 2015, al-Sisi approved the Anti-Terrorism Law (No. 94/2015), which grants security officers and prosecutors extremely wide latitude to prosecute political expression as crimes of terrorism. As documented by DAWN and other international organizations, the Supreme State Security Prosecution (SSSP) has relied on the Anti-Terrorism Law to in nearly every case it has prosecuted. These prosecutions typically target peaceful political activists or individuals without political affiliation.

The charges have primarily included "publishing and disseminating false news and information," "communicating with foreign entities to harm state security," and "joining and funding a terrorist organization" (usually the Muslim Brotherhood, which the government labeled as a terrorist organizations in 2013). Along with the Anti-Terrorism Law, the security and prosecutorial authorities have adopted a systematic practice of indefinite detention of political detainees, using permissive pretrial detention rules that permit detention without charge for up to two years, and bringing new copy-paste charges when the pretrial detention period expires.

Similarly, the Public Protest Law (No. 107/2013) restricts the rights of citizens to peacefully assemble and protest. Passed in November 2013, only a few months after al-Sisi's coup took power, the law gives security officials the right to cancel or postpone a demonstration, change the location, and alter the activity path based on "serious information or evidence" about dangers to security and peace that the security officials themselves present. Those who breach the law face a variety of financial penalties as well as prison sentences. The law also allows security forces to arbitrarily use batons and rubber bullets to disperse gatherings, rallies, and demonstrations that they perceive to be dangerous.

After the law was approved, the Ministry of Interior warned Egyptians of holding any demonstration in violation of the law. Under this law, the popular blogger and political activist Alaa Abd el Fattah was arrested for calling for protests without first gaining government permission. Likewise, the Ministry of Interior has violently dispersed protests and cited this law as legal justification for its actions.

Because of these repressive laws, there are today more than 65,000 Egyptians detained for their political association and speech. The al-Sisi government has had to open at least 34 new prisons since coming to power to keep pace. Human rights organizations have documented systematic and widespread torture and abuse of detainees, including likely crimes against humanity. Detainees have died in prisons due to deliberate medical neglect and deplorable physical conditions, such as detention without heat or hot water, being forced to sleep on bare floors, and being forced into deliberately overcrowded, tiny cells without natural light.

Finally, in September 2017, the Egyptian Parliament approved new amendments to the country's nationality law. These amendments expand the executive authority's discretionary power to withdraw nationality from Egyptian citizens. Affiliation to any foreign entity or working for foreign organizations that seek to "harm public order and destabilize the country" have become grounds for withdrawing nationality.

This amendment grants massive discretionary power to the executive to strip Egyptians of their citizenship. Under international law, it is generally unlawful for a government to strip an individual of his or her citizenship when doing so makes the affected individual stateless, particularly when the deprivation of nationality is arbitrary. Nonetheless, on December 21, 2020, the Egyptian Prime Minister issued a decision stripping 17 Egyptians of their citizenship.

Al-Sisi promised that women would be safer under his rule, while in fact gender discrimination, sexual harassment, and violence against women are systemic and pervasive.

- Al-Sisi Promised Greater Protection for Women, but the Repression and Abuse of Women Has Increased under his Government

Al-Sisi promised that women would be safer under his rule, while in fact gender discrimination, sexual harassment, and violence against women are systemic and pervasive. Under al-Sisi, women who come into contact with Egypt's criminal justice system often encounter sexual abuse, whether they are victims, witnesses, or simply interacting with the police on a different matter. Witnesses, as well as their relatives, are targeted and even arrested for reporting violence against women, including rape.

Despite these abuses, al-Sisi declared his respect for women and promised to empower them. Al-Sisi even declared 2017 the "Year of Women." Yet gender inequality, sexual abuse, and gender-based violence remain rampant. While the 2014 constitution prohibits any discrimination against women and emphasizes gender equality, reality (and data) shows a widening gender gap. For example, the 2021 Global Gender Gap Report ranked Egypt 129 out of 156 countries in its Global Gender Gap Index and 150 for women's economic participation. Within management positions, men make almost twice as much as women do for the same job (92%).

The statistics of violence against women in Egypt are staggering. A 2020 survey conducted by the National Council for Women and the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics documented that each year about 5.6 million women suffer violence from their husbands or fiancés. About 2.4 million women suffer serious injuries because of that violence and 1 million women leave the marital home due to domestic violence. About 200,000 women experience complications in pregnancy because of domestic violence, and at least 75,000 women report incidents of violence to the police. Alternative housing or shelters for domestic abuse survivors annually costs the state 585 million EGP (about $37 million).

Al-Sisi's government has targeted women for their peaceful political activism, subjecting them to horrific abuses. DAWN and others have documented these abuses and persecution, including the cases of Kholoud Said Amer, Solafa Magdy Sallam, and Hoda Abdel Moneim. There is no official number of female political detainees in Egyptian prisons, but human rights organizations conclude that at least 70 women were held in 2017 and that the number has increased since then.

Detained women have experienced torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, and sexual harassment, often alongside state-supported defamation campaigns. These violations occur during arrest, investigation, and imprisonment by police officers, prison guards, or even doctors employed by the state. Although there is no public data available, human rights groups and lawyers believe that these incidents happen frequently.

Egyptian and international human rights organizations have documented cases in which Egyptian authorities have continued to force or coerce women, especially those charged with political crimes, to undergo "virginity tests." Although an Egyptian Administrative Court ruled in 2011 that virginity tests "constitute a violation to women's bodies and an assault on their human dignity," the practice persists.

Under al-Sisi, women also face greater restrictions on their freedom in the public sphere. Women are prosecuted for using social media platforms and imprisoned on vague and baseless charges of violating "family values."

On June 21, an Egyptian court sentenced Haneen Hossam, a TikTok influencer, and her four associates to ten and six years in prison, respectively, for TikTok videos deemed offensive to the country's religious and family values. The same day, authorities detained seven other women for the same offense. Egyptian security forces also arrested Aya Ibrahim Yahya Mohamed after she posted a video on TikTok while wearing a police uniform. The SSSP accused Mohamed of joining a terrorist organization and misusing social media.

On July 12, the Egyptian House of Representatives approved a legislative amendment to toughen the penalty for sexual harassment, converting it from a misdemeanor to a felony, and increasing the minimum sentence to five years in prison. A perpetrator may receive a seven-year sentence if the harassment includes a weapon, more than one person is involved in the harassment, or the perpetrator is in a position of authority over the victim. These amendments are important steps towards deterring sexual harassment but they do not go far enough, as they do not provide sufficient protection for women against sexual harassment. Moreover, whether the al-Sisi government will enforce this amended law very much remains to be seen.

- Al-Sisi Promised to Defeat Armed Groups in Sinai, but his Secret War Rages On

Shortly after removing Morsi from office, al-Sisi promised to defeat the armed groups and end the ongoing insurgency in the Sinai Province. In October 2013, Major General Ahmed Wasfi, the Chief of Egypt's Second Army Division, declared that by the end of major military operations in Sinai, Egypt would be free of terrorism. Nearly eight years later, however, the war rages on, with scarce independent news coverage. Wasfi also claimed that no innocent citizen had been killed or injured during military operations, despite clear evidence that the government classifies civilians killed during military operations as "militants."

Egyptian armed forces began expanded military operations in the Sinai in September 2013. At the time, the armed forces faced between 800 and 1,200 armed fighters in Sinai. This number continued to grow despite the government's enhanced military approach, resulting in the killing of at least 2,500 armed fighters between September 2013 and 2017.

The National Council for Human Rights' 2021 report on the situation in Sinai stated that about 1,836 civilians were killed and 2,915 civilians were injured during military operations. All told, between 2013 and 2020, the government has reportedly destroyed 12,350 homes, and forcibly displaced over 100,000 residents.

Human rights groups have documented extensive violations of international humanitarian law and international human rights law by Egyptian military forces, including extrajudicial killings, wide-scale arrests and torture, rampant property destruction, and indiscriminate attacks. In 2019, Human Rights Watch documented that military and police personnel arrested more than 12,000 Sinai residents between July 2013 and December 2018. Security forces often placed detainees in solitary confinement, sometimes in appalling conditions, and detained children as young as 12 alongside adults.

At best, these nearly eight years of intense military operations have succeeded in containing the armed conflict in Sinai. The root causes of conflict remain unresolved and al-Sisi's government has perpetuated the conflict, rather than ending it. Non-state armed groups continue to carry out attacks against civilians and military personnel and security remains precarious.

Although counterterrorism support is a primary justification for U.S. military aid to Egypt, totaling about $1.3 billion per year, this aid at least indirectly contributes to ongoing abuses and the al-Sisi government's perpetual war in Sinai. Further, U.S. military aid is supposed to support Egypt's counterterrorism efforts, border control, and maritime security.

Egypt, however, has prioritized the purchase of weapons that have little use for counterterrorism operations, including fighter jets, amphibious assault/helicopter carrier ships, and upgrades to long-range missiles. These purchases contribute to al-Sisi's "failed war on terror, a war riddled with likely war crimes and crimes against humanity and made possible, at least in some part, by U.S. military aid.

- No Access to Information with al-Sisi as the Gatekeeper

Media outlets have been one of the primary targets that al-Sisi government officials have sought to control and use as propaganda for the government. In various public appearances, al-Sisi has boasted that the media fully supports the state's policies and praised Nasser-era ownership of media outlets. The military and other state security apparatus, especially intelligence agencies, have taken steps to ensure full control over media outlets, including taking ownership of several media and cultural institutions.

Notwithstanding the Egyptian Constitution's guarantees of freedom of and access to information, al-Sisi has used the legal authority granted to him by the Emergency Law to censor, confiscate, and even shut down media outlets. Al-Sisi also has used this law to restrict independent news and information in the country.

The media landscape also has witnessed dramatic structural change under al-Sisi, including the suspension or closure of nearly every independent newspaper in the country, the jailing of journalists deemed critical of the government, and the expanded government ownership of media companies. Journalists have faced prosecution and imprisonment under what media experts characterize as "Sisi's crusade" against the press. Between 2013 and 2020, the Egyptian government imprisoned at least 183 journalists, including 27 journalists in 2021. Several journalists have gone missing, often only to appear in court and then face lengthy pretrial detention. Reporters without Borders' 2021 World Press Freedom Index reflects the al-Sisi government's repressive approach and ranks Egypt 166 among 180 countries.

Under al-Sisi, the Egyptian military also has taken control of much of the media through proxy businesses with close ties to the security apparatus. These businesses have purchased existing media outlets, changed their editorial policies, and removed voices critical of the government. For example, in 2016, Ahmed Abou Hashima, a businessman known for his close ties to the security apparatus, bought a majority share of the Youm7 and Sout al-Ummah newspapers and the OnTv Network. In 2017, Eagle Capital, a company believed to have strong ties to Egyptian intelligence, bought Abou Hashima's shares of these media outlets.

Then, on January 20, 2019, Egyptian Media Group, owned by Eagle Capital, signed several agreements with the Supreme Council for Media Regulation, a governmental entity appointed by the president to oversee media outlets, to launch a new satellite TV channel for the Arab region. Eagle Capital owns or has significant shares in Egypt's major private TV networks, including CBC and OnTv, and newspapers, such as al Masry al Youm. Eagle Capital also owns United Media Services, a prominent production company. These and other murky financial dealings demonstrate how the al-Sisi government continues to shrink the media space in Egypt.

The government has also expanded monitoring and surveillance of content accessed on the Internet. The Cybercrime Law of June 2018 (No. 175/2018) requires Internet service providers to keep a record of their users' personal information and their online activities and to deliver this information to security authorities upon request.

The law also gives the government the authority to ban websites if it considers their content a threat to national security, but it does provide a clear definition of what constitutes a "national security threat." The Press and Media Outlets Law (No. 180/2018), also passed in 2018, expands these controls to individual accounts, websites, and blogs with 5,000 or more followers, which the law treats as media outlets. In May 2017, authorities banned hundreds of websites that they claimed to be a threat to national security. The number of banned websites has grown to about 512 as of April 2019, further demonstrating the al-Sisi government's intolerance of criticism and its consistently repressive approach to undermining a free press and the freedom of information.

- Expanded Control Over Universities, Curtailed Academic Freedom

Following the 2011 revolution, Egyptian university faculty members obtained the right to elect their university presidents and college deans. In 2014, however, al-Sisi issued a decision revoking this right, canceled the election of university presidents and college deans, and gave himself the authority to select each position from a list of three candidates nominated by the Ministry of Education. In January 2021, the Minister of Higher Education issued requirements for the selection of university presidents and college deans, modifying the selection process but still keeping the appointment of senior university officials under governmental control.

The al-Sisi government also has issued a number of administrative decisions and directives to limit academic freedom. For example, universities must obtain permission from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to hold an international conference, effectively making government approval necessary before inviting any speaker from outside the country. The al-Sisi government also prohibits universities and their faculties from entering into collaborations with foreign universities without permission from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and security authorities. University administrations frequently require faculty members to obtain permission from government security authorities before traveling abroad to attend academic conferences.

Egyptian security forces also have escalated their crackdown on academic freedom. Egyptian authorities target scholars by arresting them on vague charges of "spreading misinformation" and "joining a terrorist organization." Arrested scholars include political science professor Hazem Hosny, who was released on probation on February 23, 2021, and Ahmed Tohamy, a professor of comparative politics at Alexandria University.

The government also arrested Patrick Zaki and Ahmed Samir Santawy, both graduate students studying outside of Egypt. In both instances, the government arrested them when they returned home for brief family visits. Egyptian authorities detained and tortured Zaki, while on June 22, 2021, an Emergency State Security Court sentenced Santawy to four years in prison for comments he made on social media.