Salman Alodah, prominent scholar

Summary

Salman Alodah is one of the most popular scholars in Saudi Arabia and the Muslim world. He has advocated for reforms in Islamic discourse and campaigned for political participation, especially in Saudi Arabia. His books include 'A Budding Heart (Autobiography)', 'Questions on Revolution' and 'Questions on Violence'.

Alodah has long faced persecution by successive Saudi governments for his criticism. The General Investigation forces (al-Mabahith al-Ammah) detained him from September 1994 until July 1999 without trial over his criticisms of the Saudi government. Saudi State Security forces next arrested him in September 2017. The state prosecutor brought charges against him one year later, in September 2018, at the Specialized Criminal Court, seeking the death penalty on 37 charges related to Alodah's peaceful speech advocating reforms. His trial is ongoing.

State Security interrogators have mistreated Salman Alodah in detention and deprived him of sleep and necessary medications. He is still in solitary confinement. On October 22, 2017, at the Saudi border with Bahrain, a passports officer informed two of his family members that the Royal Court had banned all 19 members of the Alodah family from traveling. They are still banned.

Methodology

DAWN researchers include the son of Salman Alodah, Abdullah Alaoudh, who is a DAWN Researcher. He provided information, court memoranda, and other legal documents for this investigation, in addition to published sources that we consider to be reliable. DAWN researchers also interviewed three people involved in the case on May 1, 2020, June 28, 2020 and August 28, 2020, including a lawyer close to cases at the Specialized Criminal Court. Details of these interviews are withheld to protect the security of our sources.

The information and documents were obtained in August 2020.

We are not publishing most of the legal documents related to this case to protect the security of others.

Personal Background

Salman bin Fahd bin Abdullah Alodah, a Saudi citizen, was born on February 1, 1957. He is married and has 18 children. He is descended from the al-Jubur tribal sub-faction of the well-known Bani Khalid Tribe in the northern Arabian Peninsula.

Alodah's father is Fahd Alodah, and his mother is Norah al-Luhaidan.

Alodah was born and raised in al-Basr, a suburb of Buraydah City in Saudi Arabia, before moving to Buraydah to study. From an early age, he was involved in Islamic and intellectual study.

He studied in the "Hawizah/al-Andalus" school and the Scientific (Sharia) Institute in Buraydah. He memorized the Qur'an, reading under sheikhs such as Saleh al-Bulaihi and Muhammad bin Saleh al-Mansour in traditional learning circles.

He attended the College of Arabic Language and the College of Sharia at the University of Imam Muhammad bin Saud in al-Qassim. After graduating in 1979, he became a teacher at the Scientific Institute in Buraydah.

In 1983, he became a lecturer at the University of Imam Muhammad bin Saud in al-Qassim. In 1987, he obtained a Master's degree from the Department of Sunnah and Sciences from the College of Principles of Religion at the University of Imam Muhammad bin Saud in al-Qassim. He started pursuing his PhD in 1991 but his imprisonment in 1994 interrupted his study.

He worked as a lecturer at the College of Sharia until October 2, 1993, when he was fired for criticizing the Saudi government.

He was arrested in September 1994 and detained for five years.

In 1999, he was released and again began working on his PhD. He obtained a Doctorate in Sharia on March 5, 2004 from al-Jinan University in Lebanon.

Professional Background

Alodah's books include Questions on Revolution; Questions on Violence; My Enemies, I Thank you!, and other publications. The closest to his heart is his autobiography: A Budding Heart (Autobiography). Most of his books have been translated into English and other languages. Alodah participated in media programs and had his own shows on the Middle East Broadcasting Center MBC.

Alodah co-founded the Committee for the Defense of Legitimate Rights and participated in two historic petitions in the 1990s: the Memorandum of Advice and the Letter of Demands, in which petitioners called for a policy of shura (political participation) in the Kingdom.

The General Investigation forces (a secret police force focusing on political cases that was incorporated into the Presidency of State Security in 2017) first arrested Alodah in September 1994, along with a large group of leaders of Islamic Awakening movement (al-Sahwa al-Islamiyya), a movement of then-young Muslim scholars and preachers who called for peaceful change in society and government. The government brought no charges or legal proceedings against them and presented no evidence of any crimes, but detained them without charge in al-Haer Prison in Riyadh for five years.

Alodah was released in April 1999 and started his own organization called "Islam Today."

In 2011, Alodah publicly supported the Egyptian Revolution. As a result, the Saudi government took his MBC show, al-Hayat Kalimah (Life is a Word), off the air. During the Arab Spring, he urged the Saudi government to tackle issues of oppression, poverty, political detention, corruption, lack of political participation, and accountability to prevent a revolution in the country. He wrote a book titled "Questions on Revolution" that argued for democracy in Islam.

On Twitter, he became one of the most influential individuals in the Middle East, with more than 13 million followers by 2016.

He was a key advocate of the Petition Toward the State of Rights and Institutions signed by thousands of Saudis in 2011 demanding a transformation toward a constitutional monarchy with elections, basic liberties and democracy. In the same year, the Ministry of Interior (under an instruction from the Royal Court) banned Alodah from travel outside the Kingdom.

In 2013, Alodah published a statement to the Saudi government, demanding the release of prisoners of conscience.

Remarkably, Alodah had in the past won two libel cases against two government publishers in Saudi Arabia. In 2010, after a five-year long battle against al-Watan Newspaper, Alodah won his case against al-Watan newspaper, one of the largest government-controlled newspapers in Saudi Arabia, on the grounds of defamation. Alodah brought his case when the paper attributed to Alodah lenient positions on violence. Alodah vehemently denied this and filed the suit that he won.

In January 2017, Alodah won another libel case against Alarabiya, a Saudi-government controlled satellite station, on grounds that it aired false accusations of extremism against him. In both cases, the media outlets had to remove their false stories and publish apologies on front pages and clarifications that reflected Alodah's real positions. Al-Watan also had to pay a few thousand dollars that Alodah donated to a journalist training organization.

Time and Circumstances of Arrest

In June 2017, days before then deputy crown prince Muhammed bin Salman became crown prince, an official from the Ministry of Interior banned Alodah from travel, and told him that the Royal Court had ordered the ban.

Following the Saudi-Qatar crisis that erupted in June 2017, Alodah tweeted on September 9, 2017: "May Allah harmonize between their hearts for the benefit of their peoples."

On September 10, 2017, unidentified officers from the Presidency of State Security came to Alodah's house in Riyadh. They refused to show their badges, searched the house, and took Alodah away.

Two days later, State Security announced in relation to Alodah's detention that the government had discovered an "intelligence cell that was conspiring with a foreign government." After Alodah's arrest, State Security forces also arrested several intellectuals, activists, scholars, poets, and public figures as part of a nationwide crackdown against independent public persons in the country.

Alodah was detained in Dhahban prison where he remained until approximately October 2019. During his detention in Dhahban prison, he was periodically taken to al-Haer prison for hearings in his case, sometimes staying there for a few days each time. In late 2019, he was transferred to al-Haer prison, where he remains.

Charges

All of the charges against Alodah pertain to his peaceful political expressions critical of the government and association with like-minded persons, all of which are protected as fundamental human rights.

Attorney General Saud al-Mojeb, and his deputy in court, Mohammed bin Ibraheem al-Subait, asked for the death penalty against Alodah on these 37 charges:

- "Inducing corruption on earth;"

- Calling for change in the Saudi government;

- Calling for and inciting revolution in Saudi Arabia and support for the revolutions in other Arab countries;

- Joining groups and religious unions that go against the "traditions of the country's recognized scholars";

- "Swaying public opinion, inciting sedition, instigating society and the families of prisoners by demanding the release of prisoners on media platforms";

- Interfering in the affairs of a neighboring country.

- Joining the "Muslim Brotherhood";

- Praising the "Muslim Brotherhood";

- Joining the European Council for Fatwa and Research,

- Objecting to the boycott of Qatar;

- Inciting against the State and its institutions by joining a group of activists who are against the Saudi leadership;

- Publicly objecting on the radio to the Kingdom's granting exile in 2011 to the former Tunisian president Zeid El Abedine Bin Ali;

- Calling for and encouraging people to give financial donations to the Syrian revolution;

- Accepting an invitation from the Libyan government in 2010 to help negotiate the release of Islamist prisoners detained in Libya during a "national reconcilliation" between the Libyan government and political prisoners;

- Visiting Qatar on multiple occasions, including in 2015;

- Sowing sedition and stirring public opinion by posting a defamatory statement on the internet which incites the public against the State;

- Preparing, sending, and storing videos and other materials that could affect public order;

- Funding the Renaissance Forum, a public workshop organized by academics and youth in Bahrain, Qatar and Kuwait about civil society, religion, and other topics;

- Receiving text messages that reflect antagonism to the Kingdom and are critical of its policies;

- Exchanging emails with a group of people and promoting "false information" about the Kingdom's relationship with Qatar and a visit of a Saudi prince to Israel;

- Describing the Kingdom's authorities as tyrannical;

- Inciting against the State by calling for bypassing the 'Shura Counsel' to apply pressure on the decision makers through "illegitimate means";

- Expressing cynicism and sarcasm about the government's achievements;

- Harassing and defaming on Twitter an official body in charge of coordinating (public) speeches by condemning the cancellation of one of his lectures and threatening to publish its contents on social media;

- Defaming on Twitter an official body of the state;

- Condoning the sit-ins organized by families of detainees, an event that took place in Buraydah in 2011;

- Inciting people to put pressure on officials through "mob tactics" and sit-ins, and undermining governmental entities. Stirring public emotions by announcing the names of women arrested for social media posts and praising them;

- Condemning patriotism and allegiance to the government and country, stating that imprisonment is the price for freedom and justice;

- Inciting against security entities and complaining about them;

- Claiming that the Saudi leadership monopolizes wealth;

- Communicating with a person prohibited from traveling for security reasons, describing him as a role model and praising him;

- Praising the Turkish experience [in reference to Turkey's electoral and multi-party democratic system];

- Breaking his earlier vows to stay away from "areas of suspicion";

- Urging the public not to work for the General Investigations Directorate (now, the Presidency of State Security);

- Verbally attacking a member of the General Investigations Directorate and calling him names;

- Possessing a banned book ("Secular Extremism in Combating Islam"); and

- Calling for the release of a person accused of terrorism.

Trial and Legal Proceedings

September 4, 2018:

Judges Abdulaziz bin Medawi al-Jaber and Abdulaziz al-Harthy of the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh, which hears cases involving "state security" and "terrorism," held the first session of the trial against Alodah on September 4, 2018. The trial was held secretly; the family only learned about the hearing shortly before it occurred when a representative of the Specialized Criminal Court called the family to inform them. The judicial committee overseeing the case is headed by Abdulaziz bin Medawi al-Jaber.

Attorney General Saud al-Mojeb, and his deputy in court, Mohammed bin Ibraheem al-Subait, asked for the death penalty against Alodah on 37 charges under general and vague charges referenced in the Anti-Cybercrime and Counter-Terrorism laws. Articles 6 and 13 of the Anti-Cybercrime Law prohibit preparing, producing, or publishing any material that threatens the "public order, religious values, public morals, and privacy…." Article 1(a) of the Counter-Terrorism Law defines the crime of terrorism as including acts that "disturb public order" and "endanger national unity."

The Counter-Terrorism Law explicitly excludes the protections of Saudi Arabia's Law of Criminal Procedure of 2013, which otherwise limits pretrial detention to six months . Article 5 of the Counter-Terrorism law explicitly allows for indefinite pretrial detention at the discretion of the prosecutor.

During the trial, the government presented the following information as evidence of the charges against him:

- Hundreds of tweets in which Alodah criticized government projects, called for reforms, and demanded the release of prisoners; and

- Alodah's admission that he attended many conferences inside and outside Saudi Arabia, that he felt oppressed by the Saudi government and that he gave interviews to many TV channels during the Arab Spring in which he was critical of some Arab governments.

October 30, 2018:

Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy postponed the session at the request of Attorney General al-Mojeb.

February 3, 2019:

Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy postponed the session at the request of Attorney General al-Mojeb.

March 6, 2019:

Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy proceeded with this session without the presence of Alodah because State Security forces decided not to bring him to court for unstated reasons. Attorney General Al-Mojeb reiterated his demand for the death penalty and presented more tweets and posts by Alodah in which he crticized the Saudi government.

May, 1, 2019:

Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy postponed the session at the request of Attorney General al-Mojeb.

July 28, 2019:

Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy postponed the session again at the request of Attorney General al-Mojeb.

October 30, 2019:

After one year of detention without trial, Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy suddenly accelerated the session at the request of the Attorney General, and demanded a final defense from Alodah, promising a ruling on the case in the following session.

September 19, 2019:

Attorney General Saud al-Mojeb and his deputy in court, Mohammed bin Ibraheem al-Subait, asked for more time to prepare their closing statement.

November 27, 2019:

Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy decided to postpone the session again.

After the postponed session in November, Judges al-Jaber and al-Harthy scheduled October 18, 2020 to be the first session of the trial in 2020, with no explanation for delaying his trial and continuing his imprisonment without trial for an additional year

Alodah has now been detained for two years without trial.

Detention Conditions

Beginning in January 2018, Alodah's family received reports of mistreatment and of Alodah's deteriorating health. On January 17, 2018, a source with direct knowledge of Dhahban Prison where Alodah was being held told Alodah's son, Abdullah, that his father was very ill. On February 13, 2018, Alodah's family visited him for the first time, after he had been held incommunicado for five months.

During the visit, he reported mistreatment. He said during the first three to five months of his detention, while in Dhahban prison, guards shackled his feet with chains and blindfolded him when moving him between interrogation rooms and his cell. Interrogators interrogated him for more than 24 hours continuously on several occasions, not allowing him to sleep. On one occasion, when Alodah was handcuffed, the guards threw a plastic bag of food at him without removing his handcuffs. Alodah had to open the bag and remove the food with his mouth, causing damage to his teeth. Prison officials denied him necessary medication until January 2018.

Following this prolonged mistreatment, in mid January 2018 he was hospitalized for a few days for dangerously high blood pressure.

Alodah was mistreated in Haer prison as well. During his confinement there where he was brought for trial hearings, he was held in a tiny cell, approximately two meters by two meters (six feet by six feet), with no bathroom, for up to a day. During the transfers between Dhahban and Haer prisons, he was blindfolded, handcuffed, lifted in the air and thrown into the back of a transfer vehicle. He was not secured in a seat, and was thrown around the back of the vehicle as it traveled, hitting its ceiling and floor.

Once he was transferred to Haer in late 2019, he continued to be held in solitary confinement. From mid-May, 2020 to mid-September 2020, he has been held incommunicado, and deprived of contact with the outside world.

Impact on Family

On October 22, 2017, two children of Alodah attempted to travel outside Saudi Arabia. The Saudi Immigration officer denied them exit and informed them that they were banned from travel outside Saudi Arabia by an order from the Royal Court. No reason was given for the order and no specifications were provided. A total of 19 members of the family are currently banned from travelling. They inquired about their travel ban to the Presidency of State Security in early 2018, to no avail.

Repercussions against his son, Abdullah Alaoudh

In October 2017, Abdullah tried to renew his Saudi passport at the Saudi Embassy in Washington D.C., but officials there told him that his "services were suspended" in the Kingdom. This meant that the government had flagged his name and he could not complete any paperwork.

On November 7, 2017, the Saudi Foreign Ministry sent Abdullah Alaoudh an email confirming that his passport renewal request "has been cancelled" and that they "cannot complete the process of passport renewal due to the "freeze of services" imposed on him. He was offered a "pass" that authorized him only to return to Saudi Arabia.

Repercussions against his brother, Khalid Alodah

After Alodah's arrest in 2017, his brother Khalid expressed concerns on Twitter. Security forces arrested Khalid on September 12, 2017, a few hours after he tweeted. He is currently held in al-Turfiyyah Prison in suburb Buraydah City and on trial for charges of alleged "sympathy to the Muslim Brotherhood."

Violation of Rights

Saudi Arabia's persecution of Alodah violates international law. In particular, Alodah has suffered egregious breaches of his right to a fair trial, his right to be free from arbitrary detention, his right to freedom of speech and free association, and his right to be free from torture. These rights are protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights ('Universal Declaration'), which all members of the United Nations, including Saudi Arabia, are obliged to uphold. Further, Saudi Arabia is a signatory to the Arab Charter on Human Rights ('Arab Charter') and to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment ('Convention Against Torture').

Right to Freedom of Speech

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees each individual the right to freedom of expression. The right encompasses speech which is critical of the government and the political system the government espouses. Governments cannot, under article 19, restrict the right of citizens to engage in political discussion and debate (see, A/HRC/RES/12/16). Alodah's criticism of the Saudi government falls within this category of speech.

In spite of the protected nature of Alodah's speech under international law, the charges against him indicate he is being prosecuted for his speech, beliefs, and affiliations. The allegations in his indictment range from praising women arrested "for security issues," opposing the boycott of Qatar, calling for change in the Saudi government, and describing the Kingdom's authorities as tyrannical. Saudi Arabia's explicit punishment of Alodah for his political speech irrefutably breaches article 19 of the Universal Declaration.

Similarly, Alodah has suffered a breach of his right to peaceful assembly and association under article 20 of the Universal Declaration and article 28 of the Arab Charter. Nevertheless, the Saudi authorities' indictment of Alodah includes unsubstantiated allegations that he has links to the Muslim Brotherhood, visited Libya in 2010, held "meetings with the attendance of thinkers and educated people," and joined the "International Union of Muslim Scholars."

Abhorrently, Saudi Arabia seeks to make use of the death penalty in Mr. Alodah's case. Use of this form of penalty to punish free speech is unjustifiable. Article 10 and 11 of the Arab Charter expressly limit the imposition of the death penalty "only for the most serious crimes" and "under no circumstances… for a political offence." Treating the expression of dissenting views as a capital crime constitutes a manifest human rights violation.

Right to a Fair Trial

Article 10 of the Universal Declaration grants individuals the right to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal. Article 13(1) of the Arab Charter on Human Rights provides that "everyone has the right to a fair trial that affords adequate guarantees before a competent independent and impartial court." From this perspective, the prosecution of Alodah is gravely concerning; particularly in light of the imposition of the death penalty, which calls for intensified, scrupulous attention to the fairness of the judicial proceedings.

The structure of justice under the Saudi Arabian regime reveals marked defects in regards to the fairness of judicial proceedings. The Specialized Criminal Court, the Court that is trying Alodah, is not an independent and impartial tribunal for the purposes of international law, with the Committee against Torture finding that the Court is insufficiently independent of the Ministry of the Interior (see, CAT/C/SAU/CO/2, at para. 17). Without access to an independent tribunal, the decision on Alodah's punishment is fundamentally invalid.

Further, the 37 charges placed before Alodah exemplify the vague nature of the criminal law applied to Alodah's case. The expansive definition of "terrorism" deployed by the Saudi authorities has been criticized internationally; the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has found the laws to"bring within their fold the innocent and the suspect alike" (see, Opinion 10/2018, para. 56). The Committee against Torture has expressed its concern over the Penal Law for Crimes of Terrorism and its Financing, one of the few laws invoked to prosecute Alodah. The Committee notes that the law, adopted in 2014, "contains an extremely broad definition of terrorism that would enable the criminalization of acts of peaceful expression considered as 'endangering national unity' or undermining 'the reputation or position of the state.'" These concerns have been validated in Alodah's case. The prosecutor has sought the ultimate criminal penalty on the basis of an indictment that spans four pages.

Individuals charged with a criminal offence have the right to be informed promptly and in detail of the charges against them (see, General Comment No. 32, para. 31). Alodah was not told of the charges being brought against him until the beginning of his trial. The Saudi authorities arrested him without presenting badges or a warrant. They denied him access to a lawyer until his trial began a year later. This complete lack of due process constitutes a violation of Alodah's right to a fair trial. Saudi Arabia neither granted him the presumption of innocence required in criminal proceedings, nor the information necessary to mount an adequate defense.

Arbitrary Detention

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention has established categories of cases where a deprivation of liberty is arbitrary under the definition of article 9 of the Universal Declaration:

- When it is clearly impossible to invoke any legal basis justifying the deprivation of liberty.

- When the deprivation of liberty results from the deprivation of the exercise of the rights and freedoms granted by certain other rights in the Declaration or the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, including the right to freedom of speech.

- When the right to fair trial has been so gravely breached that it gives the deprivation of liberty an arbitrary character.

- [Not Applicable in this Case]

- When the deprivation of liberty constitutes a violation of international law on the grounds of discrimination, including discrimination as to political opinion, that aims towards or can result in the ignoring of equality of human beings.

Alodah's imprisonment falls under the definitions of Categories I, II, III, and V above. Consequently, his detention is arbitrary per article 9 of the Universal Declaration.

The Working Group has consistently found that for a detention to have a legal basis, a warrant must be produced to the accused at the time of arrest (see, Opinion No.10/2018, para. 46). Furthermore, authorities must inform the accused of the reasons for their arrest or the charges against them at the time of the arrest (see, A/HRC/30/37, para. 12). This was again denied in Alodah's case.

Freedom from Torture

Article 5 of the Universal Declaration prohibits torture absolutely. The Convention against Torture, the Arab Charter, and customary international law all proscribe torture, which is defined by Article 1 of the Convention against Torture as "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person" to obtain information, to punish actual or alleged acts, to intimidate, or to discriminate. In addition, the Convention against Torture equally prohibits the imposition of cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment in Article 16.

Alodah was held in solitary confinement after his arrest, from September 2017 to September 2018, without charge or trial.). He was hospitalized in January 2018. Alodah's son, Abdullah Alaoudh, wrote that his father had been blindfolded, handcuffed, deprived of sleep and medical assistance, and interrogated throughout the day and night. These descriptions raise credible claims that Alodah suffered cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment in prison that could potentially amount to torture.

The concern that Alodah was tortured is especially important when considering that the indictment refers to "interrogation admission" as the major source of evidence against the accused.

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia's treatment of Alodah constitutes a grave breach of his rights under international law. Several United Nations actors, including the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom and expression, and the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, have written to the government of Saudi Arabia to express their belief that Alodah has suffered a breach of his rights under the Universal Declaration. The letter calls for his immediate release, along with the release of all other peaceful activists currently detained.

Officials Involved in Prosecution and Detention

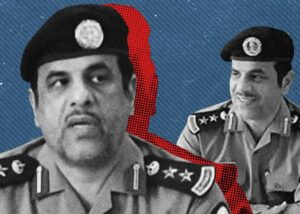

1- Major General Salah al-Jutaili, Director of the Legal Department at the Presidency of State Security

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

[PHOTO NOT AVAILABLE. IF YOU HAVE PHOTOS AVAILABLE, PLEASE EMAIL SAUDIINFO@DAWNMENA.ORG]:

As head of the legal department, Maj. Gen. Salah al-Jutaili oversees and authorizes prosecutions, interrogations, house searches, and arrests by State Security personnel; he also oversees the treatment of prisoners prosecuted by State Security. Under his supervision, the Presidency of State Security has been responsible for unjust arrests, interrogations, and prosecutions, as well as the deliberate mistreatment of detainees prosecuted by the Presidency of State Security in prison, including prolonged incommunicado detention, the deprivation of family visits and calls, and adequate food and medical care.

According to a former colleague of al-Jutaili whom DAWN interviewed on June 28, 2020, al-Jutaili has overseen Alodah's interrogations and prosecution, and has authorized his mistreatment in prison. .

2- Brigadier-General Adel al-Subhi, Warden of Dhahban Prison in Jeddah

Brig. Gen. Adel al-Subhi is the warden of the Dhahban Prison responsible for the treatment of those confined there. In 2017 and 2018, while in Dahban, Alodah was mistreated, deprived of sleep, deprived of needed medication and held in prolonged solitary confinement without justification.

3- Colonel Saad al-Salloum, Warden of al-Haer Prison (General Intelligence Directorate Prison in al-Haer)

3- Colonel Saad al-Salloum, Warden of al-Haer Prison (General Intelligence Directorate Prison in al-Haer)

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Al-Salloum bears overall responsibility for the treatment of prisoners in al-Haer Prison. As warden, he oversaw Salman Alodah's mistreatment since 2018, including his prolonged solitary confinement with no justification. From mid-May to mid-September 2020, Alodah was held in incommunicado confinement in al-Haer Prison.

4- Saud al-Mojeb, Attorney General of Saudi Arabia

4- Saud al-Mojeb, Attorney General of Saudi Arabia

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

King Salman appointed Saud al-Mojeb as the new attorney general, just four days before the major political reshuffle in which he named Mohammad bin Salman crown prince in June 2017. Prior to assuming his current position, al-Mojeb served first as a judge and then as a member of the Supreme Judicial Council. His experience almost exclusively involved personal status (family law) cases. He also serves as a member of the controversial National Anti-Corruption Commission, headed by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

As attorney general, al-Mojeb bears overall responsibility for prosecuting Alodah for his peaceful speech and activism, which are protected by international human rights law. Al-Mojeb kept him in arbitrary and pretrial detention for one year when he was held without access to lawyers and without being charged with a crime.

5- Abdul Aziz bin Safar al-Adhiani Al-Beniusi al-Harthi, Judge at the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh

5- Abdul Aziz bin Safar al-Adhiani Al-Beniusi al-Harthi, Judge at the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Judge Abdulaziz al-Harthy was born in Taif city in Saudi Arabia. In 2012, al-Harthy obtained a master's degree from Imam Muhammad bin Saud University, according to records in King Fahad National Library. In May 2020, al-Harthy obtained a PhD in comparative jurisprudence from the Judicial High Institute at Imam Muhammad bin Saud Islamic University, an institute that trains judges in Saudi Arabia.

Al-Harthy serves on the judicial committee of Salman Alodah's case at the Specialized Criminal Court.

At multiple hearings, al-Harthi did not once allow Alodah's lawyer to speak in court. Al-Harthi also interrupted Alodah, requesting him not to speak to defend himself. At one hearing, in an unprecedented move, the Court proceeded in hearing Alodah's case in Alodah's absence while he was in jail.

6- Abdulaziz bin Medawi al-Jaber, Judge at the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh

6- Abdulaziz bin Medawi al-Jaber, Judge at the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Born in Abha in the south of Saudi Arabia, al-Jaber studied at the Scientific Institute in Abha, according to an extensive (five-episode) interview with his family broadcasted on al-Majd TV in 2010.

He graduated with a bachelor's and master's in jurisprudence. On April 13, 2013, al-Jaber obtained his PhD from the Islamic University of Madinah.

According to the Saudi news outlet Sabq, he represented the Ministry of Justice as part of a Saudi judicial delegation that traveled to Europe and the US.

Al-Jaber sat as a judge for the General Court in Yadamah governorate in Najran, in the south of Saudi Arabia, before receiving a promotion to President of the General Court of Yadamah governorate until August 2008, according to Riyadh Newspaper. He also sat as a judge at the Criminal Court in Jeddah Governorate, and has served as the Assistant Head of the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh since 2018, according to Sabq.

In 2011, Judge Abdulaziz bin Medawi al-Jaber presided over the cases of Yusuf al-Ahmad, Abd al-Rahman al-Sayyid, Abd al-Majeed al-Muhanna, and other conservative scholars and activists who demanded the implementation of the Criminal Procedure Law in the Kingdom, according to the campaign statement of Yousef al-Ahmed in 2011. Al-Jaber sentenced al-Ahmed to five years in prison.

In an unfair trial, Judge al-Jaber sentenced 15 individuals from the Shiite minority to death allegedly for spying for the Iranian government. They were executed on December 6, 2016.

According to the Saudi lawyer and Director of the European Saudi Organization for Human Rights (ESOHR), Ali Adubisi, Judge al-Jaber sentenced a minor, Abdullah al-Zaher from the Shiite minority to death in October 2014. Authorities arrested him at the age of 15 in March 2012 during public protests in the city of Qatif in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia.

At one hearing, Judge al-Jaber proceeded in Alodah's case without his presence, unlawful under Saudi Arabia's procedural law and court practices.

Local Saudi Coverage

A few months after the arrests of Alodah and others in September 2017, Alodah's son, Abdullah, in January 2018, indicated that his father had been held incommunicado and that the family was worried about his health. During this incommunicado detention, Abdulaziz Kasem, a journalist aligned with the Saudi government and its security apparatuses, wrote an article attempting to claim that Alodah was comfortable and happy in prison and satisfied with his imprisonment. The Presidency of State Security and Dhahban Prison Administration headed by Brig. Gen. Adel al-Subhi allowed Kasem to visit Alodah in Dhahban Prison on January 31, 2018, before Alodah's family was allowed to visit him.

Kasem wrote a piece describing Alodah as a scholar living in a comfortable "garden" in Dhahban prison "enjoying his time". Kasem said that Saudi political prisons are like "places for leisure and relaxation."

Kasem also conveyed a message that he claimed was from Alodah to his son, Abdullah, to stop advocating and campaigning for him. "Just focus on your study. You do not know anything about what happens here," Kasem claimed Alodah told his son. When Kasem asked Alodah about his health, he claimed Alodah said he missed some medications on one occasion and was rushed to the hospital, but turned out fine and healthy. Kasem also claimed that Alodah accepted the government decision to jail him, saying "if the government wants to keep me in jail, that's fine in order to preserve the public interest."

When Alodah's family was able to visit him in Dhahban Prison for the first time in February 2018, Alodah contradicted all of Kasem's claims. Alodah explained that his hospitalization was due to mistreatment and denial of medications.

This also contradicted the family's account during the visits.

Abdullah bin Bejad Alotaibi similarly wrote an attack piece on Alodah. In a column on September 16, 2017 in al-Sharq al-Awsat, also aligned with the Saudi government, claiming that people arrested in the crackdown, including Alodah, were "agents" of foregin governments and described them as "an intelligence cell." His article was republished by Alarabiya.

Sky News, owned by an Emirati Royal, also reported on what it called an uncovered "intelligence cell", referring to Alodah's arrests among those arrested in the September 2017 crackdown. The Saudi newspaper, al-Jazirah (not to be confused with Qatar-based Al-Jazeera News), published an article by Saad bin Abdullah al-Quaiee on September 15, 2017 in which he called those detained including Alodah, "agents of a foreign government" and warned against other "sleeper cells" of foreign governments.

International Reactions

On January 2, 2018, United Nations experts released a statement decrying the arrest of "leading human rights defenders [who were] held since September [that] include reformist Salman [Alodah,] an influential religious figure who has urged greater respect for human rights within Sharia."

A few days after the arrests, Amnesty International released a report condemning the government's actions and mentioning Alodah.

On September 15, 2017, Human Rights Watch denounced the arrests against Alodah.

On January 7, 2018, Human Rights Watch released a report about Alodah's continuous arbitrary detention.

Amnesty International released a report about Alodah's hospitalization after five months in solitary confinement.

Later in January 2018, two prominent British lawyers asked the UN Human Rights Council to suspend Saudi Arabia from the UN body because of the continued Saudi mistreatment of intellectuals, scholars, activists, and public figures. They referred to Alodah's case as an "arbitrary detention" exercised "in breach of both Saudi and international law."

The 2019 Country Report on Human Rights Practices, published by the U.S. Department of State, mentioned Alodah as an example of one of the Kingdom's human rights violations.

On June 6, 2019, the Geneva Council for Rights and Liberties delivered an "urgent appeal" to the UN Special Rapporteur, asking that the Human Rights Council (HRC) place pressure on the government to halt the arbitrary execution of Alodah and other human rights advocates in Saudi Arabia.

On March 5, 2020, the MENA Rights Group, along with ALQST and the Right Livelihood Award Foundation, delivered an oral statement before the UN HRC, arguing that the imprisonment and prosecution of Alodah was meant to stifle freedom of speech in Saudi Arabia.