Gianluca Costantini is an Italian artist, cartoonist, illustrator and activist. He has contributed to numerous publications and is the author of several graphic novels. He collaborates with organizations such as the Committee to Protect Journalists, ActionAid, and SOS Méditerranée. In 2019, he received the Art and Human Rights Award from Amnesty International.

Journalists are supposed to be protected under international law. The Geneva Conventions were updated in 1977, following the Vietnam War, to expressly declare that journalists covering armed conflicts must be considered civilians and protected as such. Without journalists, we would not know the full scope of war—from the counter-narrative of the Spanish Civil War and the various horrors of World War II, to what was really happening on the ground in Vietnam and, later, in Iraq.

Every time a journalist is killed in war, a piece of truth is taken away from us.

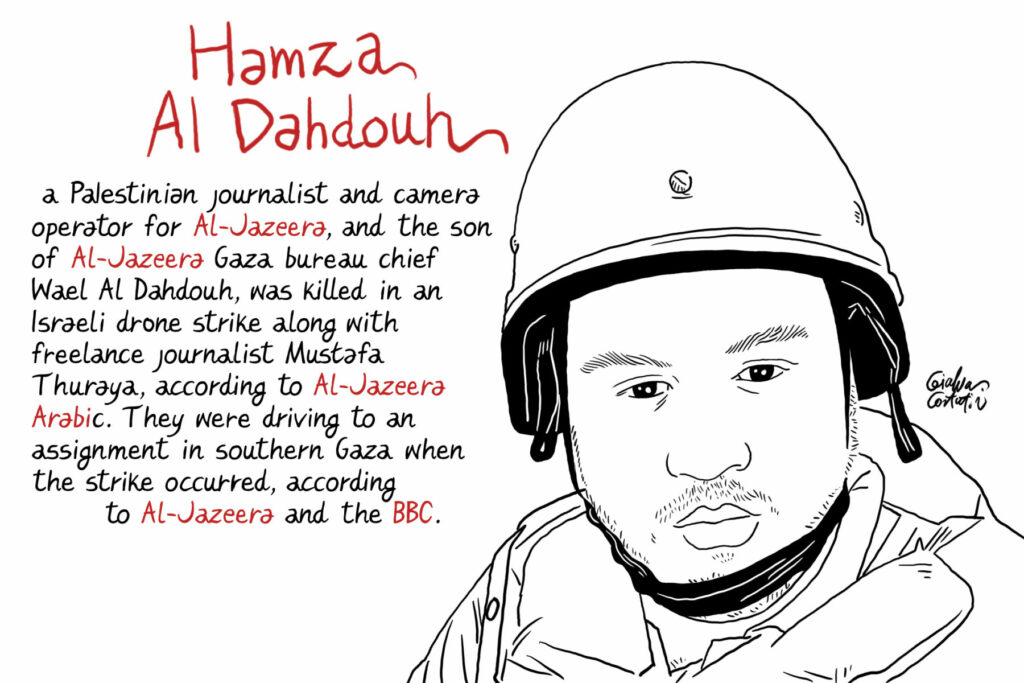

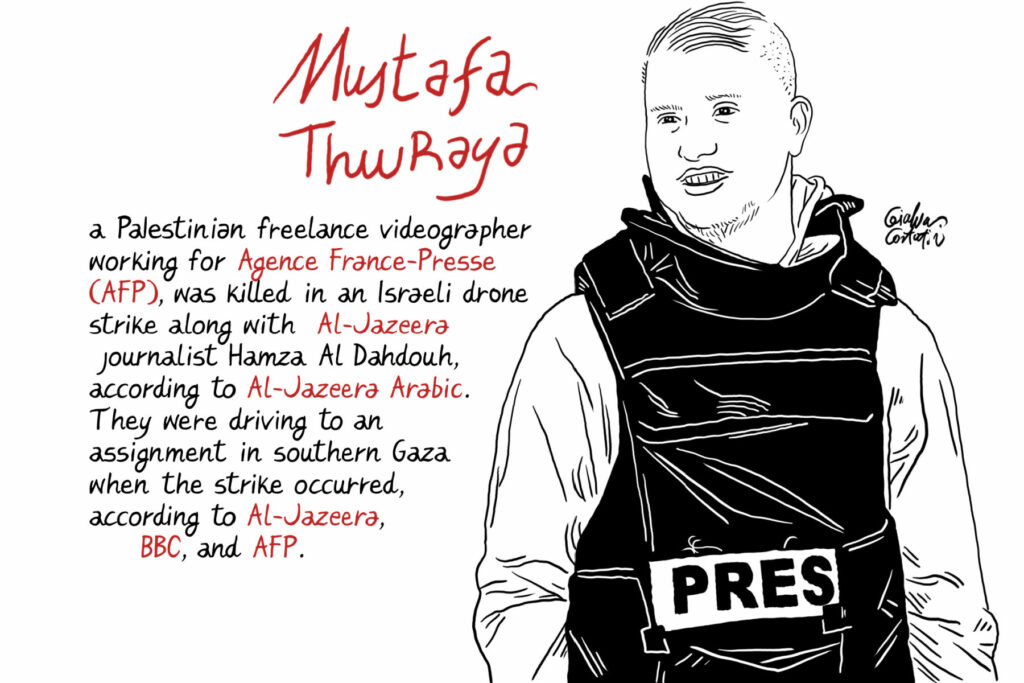

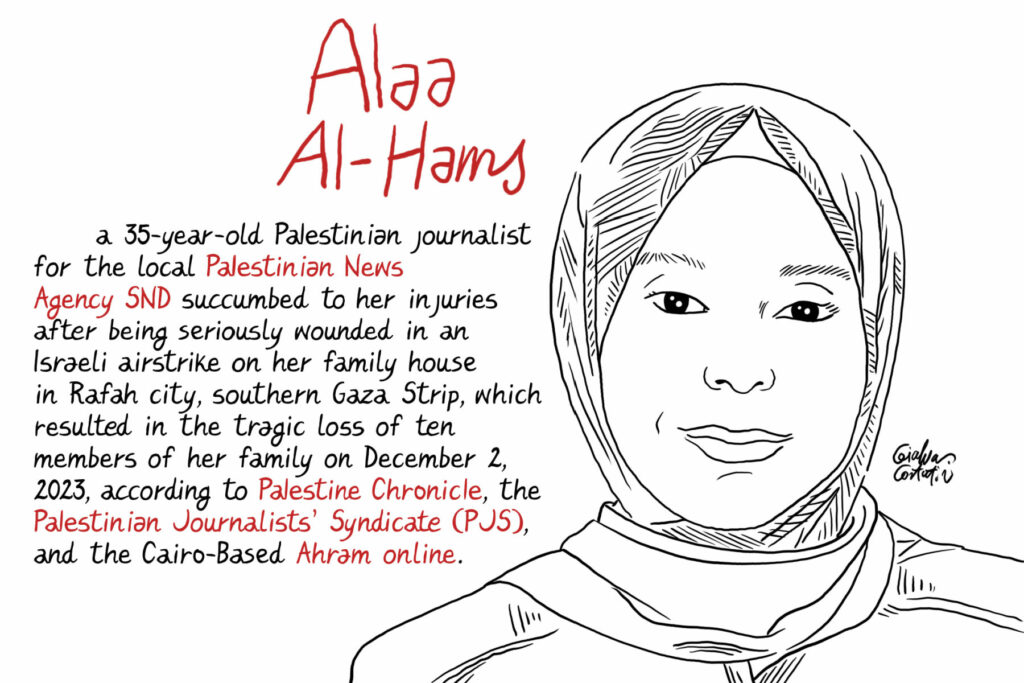

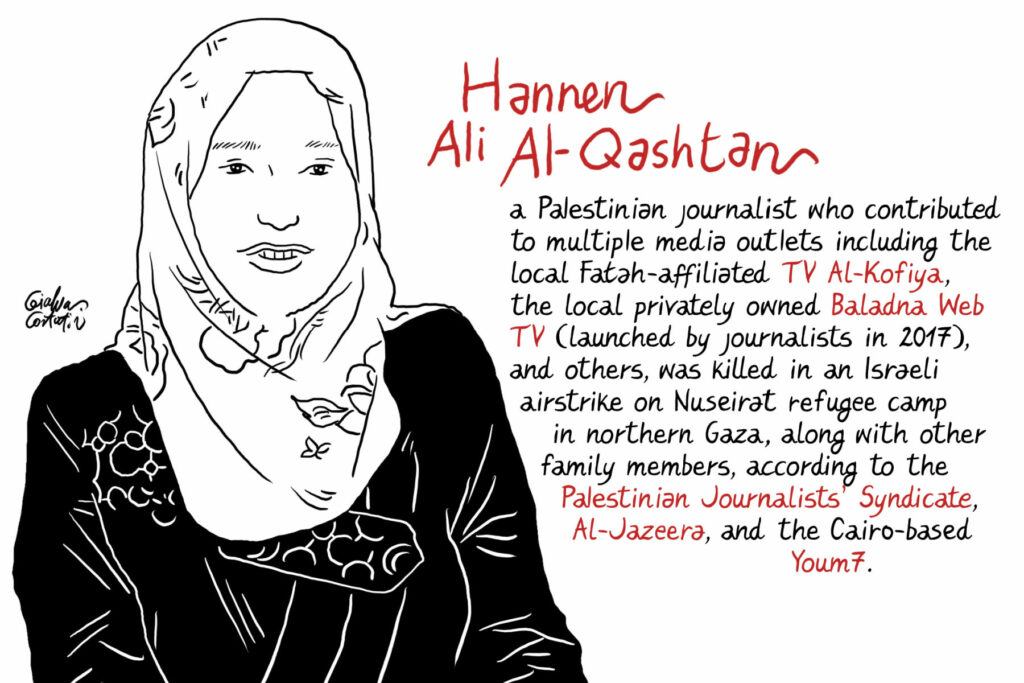

Israel's ongoing war in Gaza has taken an unprecedented toll on journalists, among its other devastation. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 108 journalists have been killed since Israel declared war on Hamas following its attack into southern Israel on Oct. 7—103 of them Palestinian, two Israeli and three Lebanese. This represents the deadliest period for journalists since 1992, when CPJ began collecting this data.

"The Israel-Gaza war is the most dangerous situation for journalists we have ever seen, and these figures show that clearly," Sherif Mansour, CPJ's Middle East and North Africa program coordinator, said in December, less than three months into the war. "The Israeli army has killed more journalists in 10 weeks than any other army or entity has in any single year. And with every journalist killed, the war becomes harder to document and to understand."

Additionally, there are reports of threats against Palestinian journalists and their families by Israeli forces, alongside widespread media censorship imposed by the Israeli government, which has also shut down Al Jazeera's operations in the country.

How did this happen? And how can there be any hope of retrospectively understanding what transpired in Gaza in these months of bloodshed if journalists are physically eliminated, without recognizing that this undermines the very possibility of truth?

How can there be any hope of retrospectively understanding what transpired in Gaza in these months of bloodshed if journalists are physically eliminated, without recognizing that this undermines the very possibility of truth?

- Gianluca Costantini

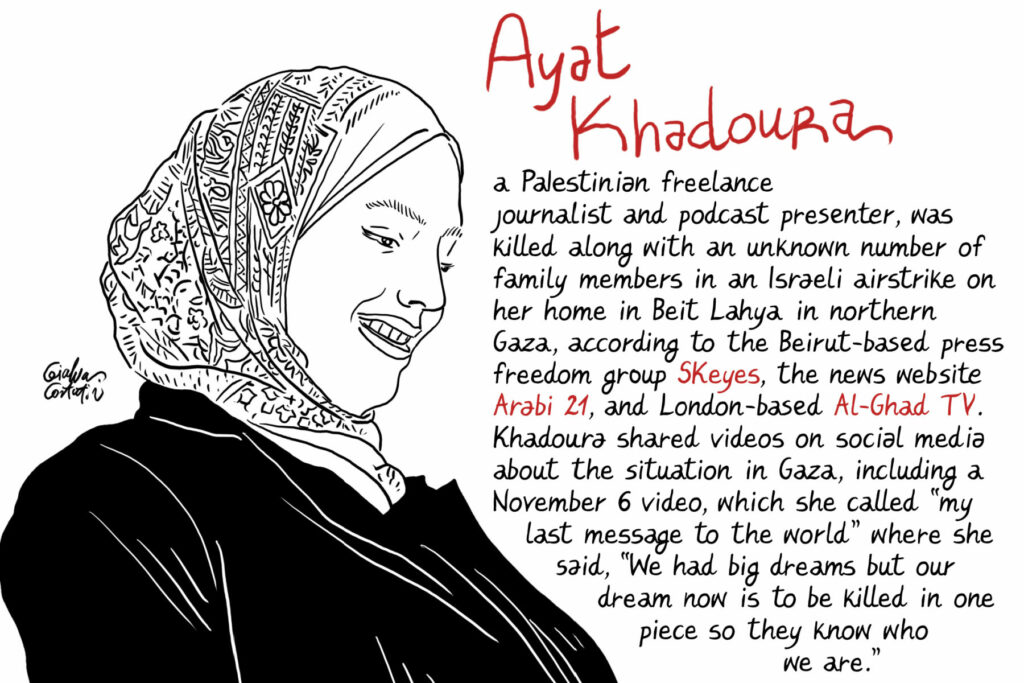

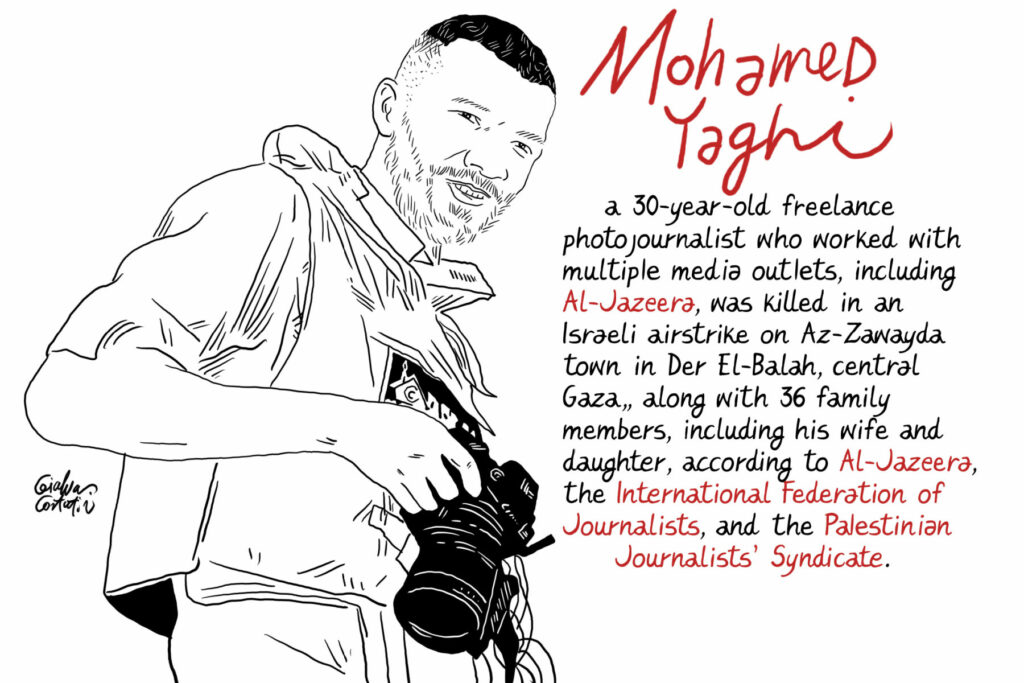

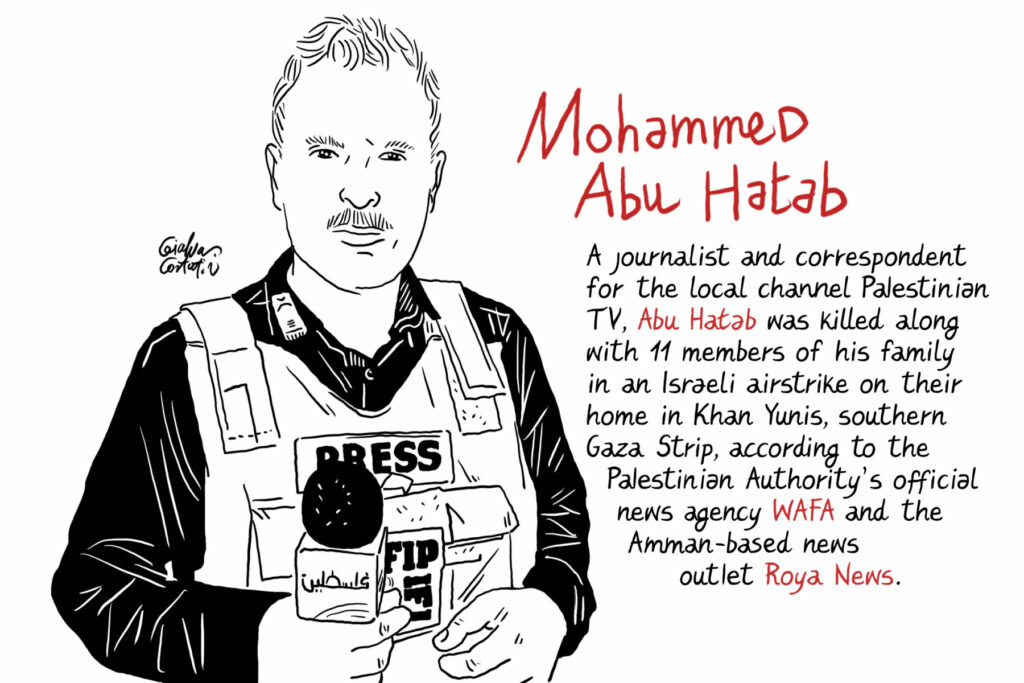

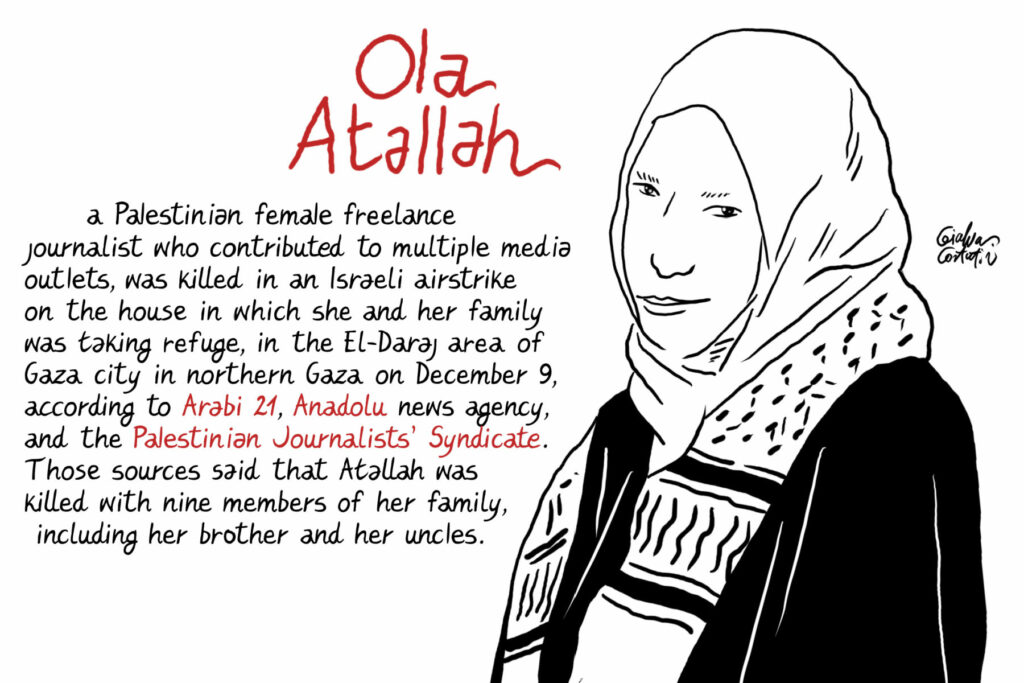

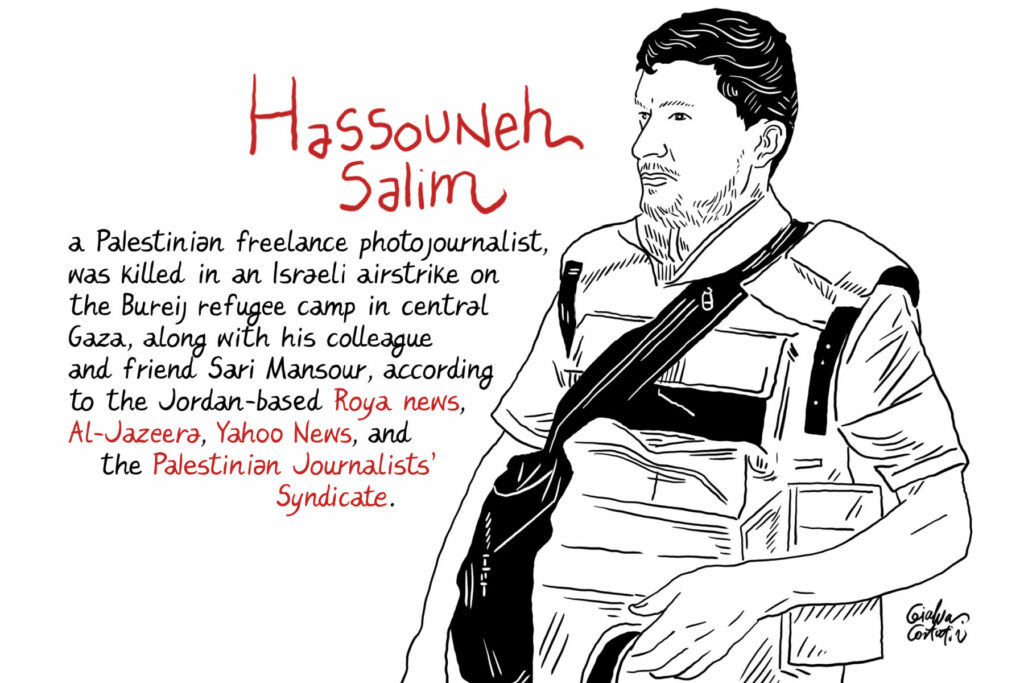

My commitment as an artist and political activist to depicting victims of human rights abuses around the world—helping to raise their voices by drawing them—does not aim to restore what has been taken away; that is impossible. Instead, it is a votive offering, a gesture of care for the memory of those who are no longer with us and who had chosen the task of bearing witness as their mission on this earth. It is a contemporary nekyia, seeking to foster dialogue between the living and the dead.

The portraits have already been used in anti-war protests in Atlanta and Seattle, as often happens with much of my political art. The drawings become part of the protests, held in the hands of citizens demonstrating in distant places to demand truth and justice, to seek answers—and in this case, to call for a cease-fire in Gaza. But also, the purpose of my drawings of these journalists is to not forget them.

As Elpenor asked Odysseus: "I beg you, my lord, remember me. When you sail from there, do not leave me behind, unwept, unburied, and turn away, lest I prove a source of divine anger against you. Burn me, with whatever armor I own, and heap up a mound for me on the grey sea's shore, in memory of a man of no fortune, that I may be known by those yet to be."

Maybe we don't want to be the object of divine anger, either, and we need to build a memorial for those yet to be. Drawing these journalists starts by carefully selecting a photo from which to create a portrait—not an easy thing to do, as many journalists and media professionals are not in this work for themselves, but to document others. My drawings of these journalists are a form of extreme gratitude, a collective ritual of atonement, a steadfast desire aimed at not letting go of the face of our loved ones, even if we have never met them, even if we will never know them now.

It is a work in progress that closely follows the map of the massacre recorded by CPJ, citing sources and serving as an explicit political warning. Until Gaza, no war had claimed the lives of so many journalists in such a short time.

Until Gaza, no war had claimed the lives of so many journalists in such a short time.

- Gianluca Costantini