Farah Abdessamad is a French-Tunisian essayist and critic.

"Food and intoxication. Scented wood is burning. Home?"

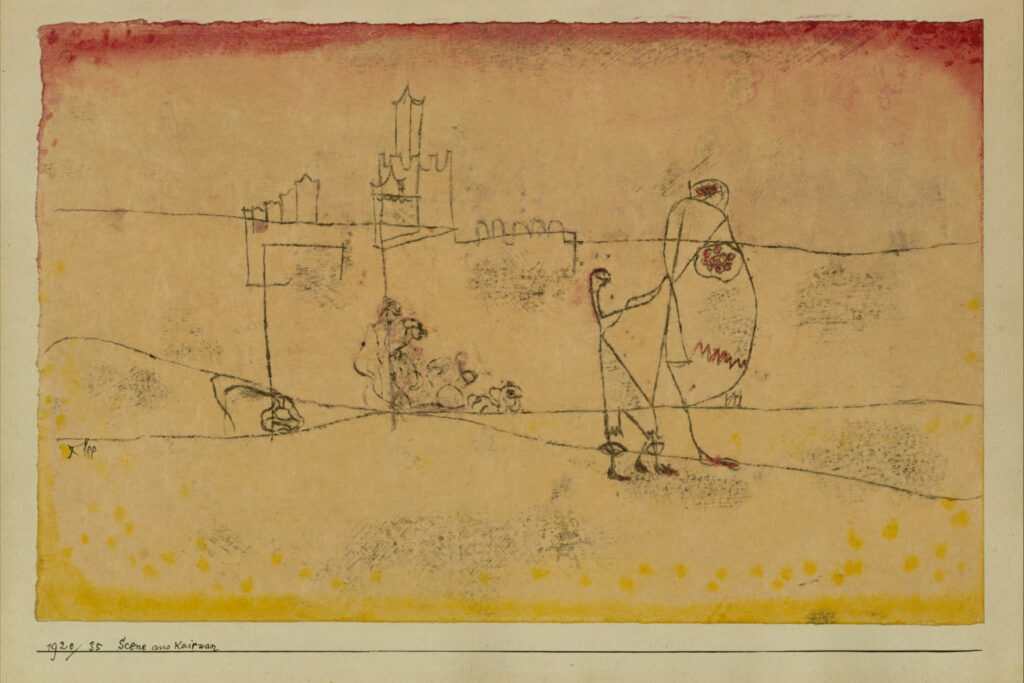

April 1914. Three days after this epiphany in Kairouan, Swiss-born German painter Paul Klee left Tunisia as a transformed man, a changed artist who had discovered the boundless potential of color and inner expression. Before Kairouan, Klee had visited Tunis, Ezzahra—a suburban, coastal town close to Tunis and my family's home—and Hammamet. He traveled there with fellow artists August Macke and Louis Moillet, his "friends of the brush."

In Klee's post-Tunisia period, I've noticed the persistence of a sun, of a circle that wants to exist for itself. A clear, red circle appears in Cacodemonic (1916); Full Moon (1919); With the Setting Sun (1919); Bird Wandering Off (1921), with its pyramidal motifs; Fire in the Evening (1929), which takes the shape of a red square; and more.

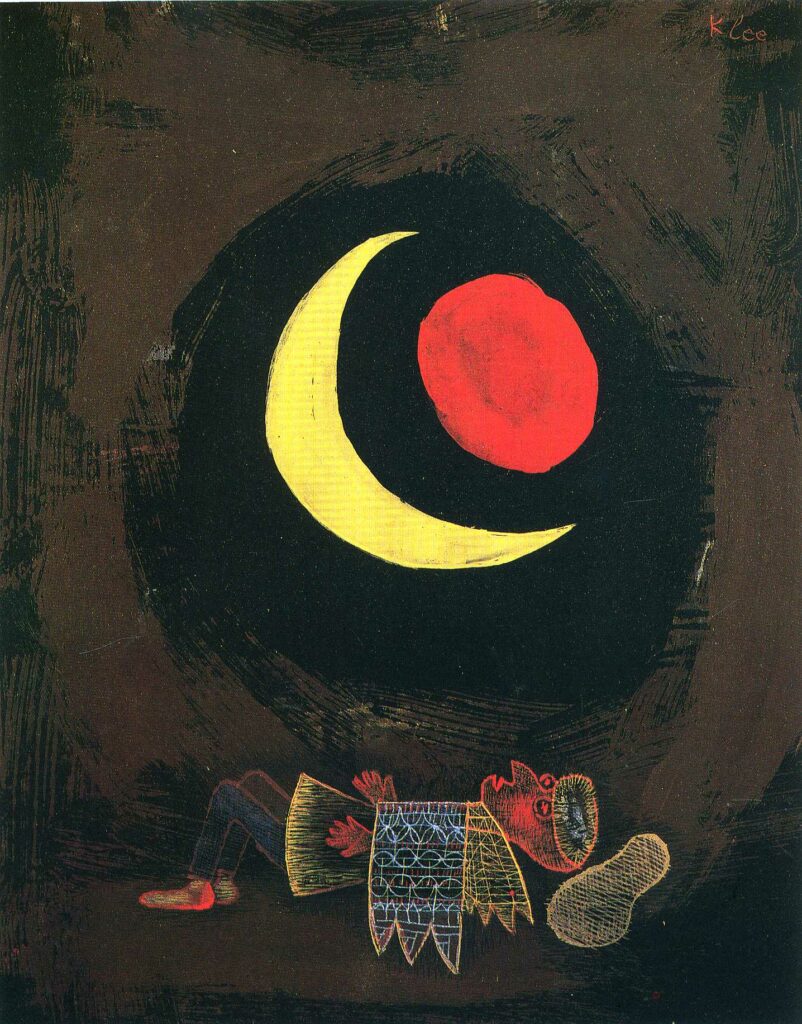

I remembered this connection when I came across the allegoric scene of Strong Dream, painted in 1929 shortly after Klee's trip to Egypt. There, he saw the pyramids, temples and tombs of Giza, and traveled south to Luxor, Karnak and Aswan. The red circle is not the same as other, similar-looking yellow shapes that also populate some of Klee's paintings.

Strong Dream takes my breath away. It exudes an atmosphere of suspension and the presence of loud, vivid symbols. In the artwork, a person is lying down, head against a bean-shaped pillow. This person is painted as a colorful, unfilled outline of negative space. Their eyes are open; they look above to a yellow crescent moon hugging a red circle—the boldest of reds. The oversized crescent and the circle emerge out of a black envelope. Their skin includes the same red. It becomes a surface that "lives" or "connects" with celestial shapes.

This red circle could be the Sun. Yet more than a solar light, it's fire. And in this vision, the sleeper likely never slept. They saw a new star and it's stirring their soul. They're questioning reality and the meaning of their own existence because the sky is our flesh; it's home. And when it changes, we change a little, too.

Stars are human friends—hundreds of them were named by Islamic astronomers, consigned for many in Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's 10th-century astronomy text, The Book of Fixed Stars. The property of stars is to guide, both artistically and practically. I think—I know—that Strong Dream is about the human discovery of Mars, as I came to consider it under a new light during the pandemic when it became certain that soon, a new history of Arabs in space would be written.

Three days after his epiphany in Kairouan, Swiss-born German painter Paul Klee left Tunisia as a transformed man, a changed artist who had discovered the boundless potential of color and inner expression.

- Farah Abdessamad

Although planets are not exactly stars, like them Mars is first a mirror of our past. In the early Late Bronze Age, more than 3,000 years before us, Mars had been recorded in human affairs. The star-planet featured in the embellishments of Pharaoh Seti I's tomb in ancient Egypt. It was represented as an avatar of the zoomorphic god Horus, the miracle child of Isis and Osiris who avenged his father for the injustices he experienced. Mars symbolizes justice.

Further East, the Mesopotamians associated the planet with their war deity, Nergal, a fire-god that embodied the closeness of the burning sun, the hunter, the destructive heat of harsh summer when crops dry out and perish. Nergal oversaw sunsets. As such, he co-ruled the underworld and judged the souls.

In 1971, NASA's Mariner 9 reached Mars—the first spacecraft to orbit another planet, its mission to map the surface in thousands of photographs. With those images, the U.S. Geological Survey named and numbered 30 cartographic quadrangles for easier navigation on Mars—using the diminutive of MC for Mars Chart. The reverential birthing of the Martian "regions" conveyed nothing of the 1970s. They leaned on Western classicism and pseudo-gravitas, as if it had already been conquered by one culture over others.

Like the ancient travelers Strabo or Ibn Battuta, I took a virtual stroll along Mars' features to acquaint myself with these names before they become a new normal. Several MCs relate to physical features, such as ancient rivers or mountains. Most MCs, though, relate to existing regions of the ancient Mediterranean world. It's odd. I'm stepping back into a mythological past while seeking to grasp a human future.

For instance, MC-13, Syrtis Major, or the "Great Sirte," is located Earth-side on the coastline of modern-day Libya: the Gulf of Sirte. MC-9 Tharsis is named after the ancient city of Thartessos in Andalusia. Tharsis was associated with forging, a detail that echoes with the Martian region's numerous volcanoes.

And of interest to me when scrutinizing this new atlas of possibilities was MC-12, Arabia. I longed for an evidence of familiarity or a legacy. What does Arabia look like on Mars, and would it be as intimately strange as I think I wanted it to be? On a Mercator projection, the area seems to host craters of various depths and sizes against an orange-rusty background. At first glance, it's as if a Western-supported coalition had bombarded Jordan's Wadi Rum, or armed drones had swarmed over Egypt's Sinai Peninsula. When I tried to focus on the photos, they vaguely evoked the Harrat Khaybar, the stratovolcano fields of western Arabia, or the shape of viscous drops of corrosive acid leaking over an iron shield. In other words, I saw destruction and inhospitality, rocks and dust, and sediments. I imagined a new home of Bedouins and Nabateans navigating a primordial vista in long-stretched walks leading them to mountains, caves and nooks, facing desert storms. I realized then that MC-12 is a no-place, an uncanny glass dream of earthling projections.

Poetically, the "Lake of Phoenix" (MC-17, Phoenicis Lacus) recalls the mythical bird of Arabian origins. The quadrangle is home to a 20-kilometer-high mountain and a dazzling geological phenomenon called the "Labyrinth of Night" (Noctis Labyrinthus), a chiaroscuro, shingles-like rash on the skin of Mars, reminiscent of the movement and depth I had seen in Klee's Crystal Gradation (1921).

Mars' exogeology is rich and it expresses itself through a bizarre, antiquated linguistic realm. Latin is the imposed language of extraterrestrial life. It is in the albedo features, which reflect the brightness on Mars' surface coming from the Sun's light, observed by the planet's earliest astronomers. And Latin is in the catenae, the chains of craters resulting from the collapse of former lava tunnels. No sign of Arabic, the language of stars. It's defunct, and I'm not sure how to mourn this.

Paul Klee felt the power of the sublime in Tunisia, and it left him in an altered state.

- Farah Abdessamad

Paul Klee had written in his diary in 1916, a year of war and loss, "and to work my way out of ruins, I had to fly. And I flew. I remain in this ruined world only in memory, as one occasionally does in retrospect. Thus I am 'abstract with memories.'" The sleeper of Klee's Strong Dream has wings. Stars hover above his mid-section belly—they feed each other; they need each other. He's both an astronaut and intronaut.

Klee felt the power of the sublime in Tunisia, and it left him in an altered state. His diary recalls how he immediately left Kairouan, for how strong of an impact the short stay had on him. "Today I had to be alone; what I had experienced was too powerful. I had to leave to regain my senses," he wrote.

Kairouan, the first Arab city in North Africa founded by the Umayyad dynasty around 670, was a major education center for Sunni scholarship during the Islamic Golden Age. It was also the political capital of Ifriqiyah, until it transferred to Tunis in the 12th century. Some qualify Kairouan as the fourth holiest city in Islam after Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem. For this reason, Kairouan was closed to non-believers until 1881, when the conquering French struck a deal with the local authorities: no bloodshed in exchange for full access to the city. As a result, foreign visitors could tour mosques and other significant locations against local sentiments. Foreigners rushed, attracted to an orientalist appeal and the advent of photography. On film, the images they took home betrayed the sanctity of places that were not supposed to be divulged—least not to profane eyes, such as the medina's Great Mosque and the Mosque of the Three Doors, two of the oldest Islamic monuments in the world.

Among the sites that Klee must have seen in Tunisia were the tombs of marabouts, holy men (sometimes women) and leaders of Sufi zaouias. The veneration of marabouts and their following likely have their roots in pre-Islamic beliefs. Often ascetic and wandering, marabouts are considered to possess extraordinary abilities, or baraka, a divine gift, stemming from a particular connection with God, and in other words, the cosmos. Tunisia shares this Sufi tradition with many other countries on the continent and beyond.

Red, found on the entrance door of these qobas, as the domed structures are known, also defines our national flag, in which a crescent hugs a star (eerily similar to the iconography of Klee's Strong Dream). Klee saw and experienced color in North Africa. His red may pay tribute to the delicious visual stain of chechias, the traditional felt hats of my ancestors that my father also keeps, or the harissa paste that burns our tongue and feeds us. Color is an image and feeling under his brush, and red murmurs the gravitational pull of a spiritual home, the one we dream about. Red is what remains alive in memory; it's the perfect grammar of abstraction.

In February 2021, the first Arab probe sent by the United Arab Emirates reached Mars' orbit. It's called Hope—as a sign that we've likely given up on finding any on Earth for our kin. And just days ago, astronaut Sultan Al Neyadi, from Al Ain, completed a spacewalk outside the International Space Station—the first Arab to walk in space. And one day possibly, we'll speak Latin on the red planet.

Far from the medieval observatories of Baghdad, Constantinople and Damascus, I listened to audio from Mars on my laptop, from NASA's Perseverance Rover. It's surprisingly accessible. I heard something, a breeze, a muffle sound. It carries an exo-heartbeat, a proof of faraway life. In those scratches maybe, the imaginary steps of semi-nomads setting camp in MC-12, Arabia. The record of a storm and a dream.

![Security forces loyal to the interim Syrian government stand guard at a checkpoint previously held by supporters of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, in the town of Hmeimim, in the coastal province of Latakia, on March 11, 2025. Syria's new authorities announced on March 10, the end of an operation against loyalists of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, after a war monitor reported more than 1,000 civilians killed in the worst violence since his overthrow. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the overwhelming majority of the 1,068 civilians killed since March 6, were members of the Alawite minority who were executed by the security forces or allied groups. (Photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR / AFP) / “The erroneous mention[s] appearing in the metadata of this photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR has been modified in AFP systems in the following manner: [Hmeimim] instead of [Ayn Shiqaq]. Please immediately remove the erroneous mention[s] from all your online services and delete it (them) from your servers. If you have been authorized by AFP to distribute it (them) to third parties, please ensure that the same actions are carried out by them. Failure to promptly comply with these instructions will entail liability on your part for any continued or post notification usage. Therefore we thank you very much for all your attention and prompt action. We are sorry for the inconvenience this notification may cause and remain at your disposal for any further information you may require.”](https://dawnmena.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/syria-22039885951-360x180.jpg)