Arie Amaya-Akkermans is a writer, art critic and independent researcher based in Italy. His work focuses on the history of archaeology, contemporary art and the politics of memory in the Middle East.

A towering figure in Lebanon's art scene whose influence extended throughout modern Arab art, 96-year-old Lebanese painter Yvette Achkar died on the morning of May 12, according to an announcement by her family. Although regarded as a prolific pioneer in postwar abstract painting who exhibited her work in Lebanon for some 50 years, there have been few obituaries since her death. This is not simply the case of an artist who might have been forgotten. Aside from expected obstacles, such as the absence of historical archives in Lebanon, the precarious position of women in modern art or the overvaluation of postwar conceptual art, there were particular difficulties unique to Achkar in her long artistic career. Not only was she a deeply private person who left very little behind in the form of a commentary to her hermetic, signature style, but she also rejected labels such as abstract or woman painter.

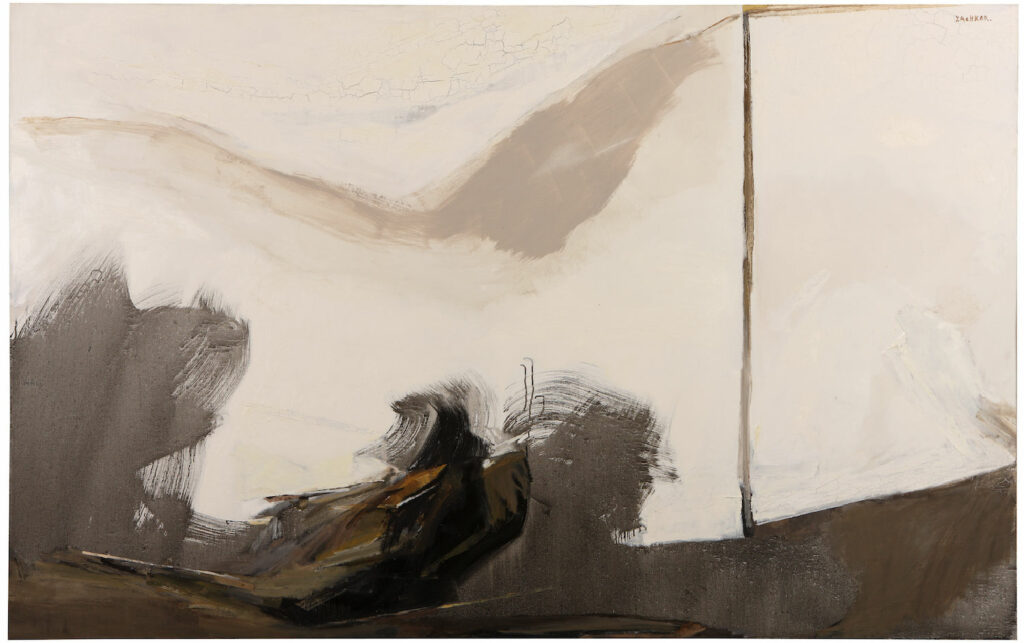

Her iconic canvases are monumental color fields in bright pastel colors, with heavy centers of gravity that seem suspended or crushed by the weight of the surface. In her later work, the center began to disintegrate into a thin line, perhaps an allusion to mortality and the shrinking of time. Once you have seen Achkar's work, you recognize it anywhere, and it is difficult to forget. But the interpretation of the work is a much more complicated affair. When I began writing about her paintings after a visit to her Mount Lebanon studio in 2014, despite consulting five decades of newspaper articles and interviews, my ideas seemed to go nowhere. There was so much to say, but no way to decipher the artist's imagery. It took me a decade to complete a modest overview of her career and formulate a few basic ideas about what she might have wanted to say. Less than two months later, Achkar passed away.

Now, it is all too clear: Achkar would be one of the last abstract painters in Lebanon and the wider region whose work was directly connected to the turbulent history of 20th-century European abstraction. Her work is intricately linked both to the meteoric rise in Paris in the 1950s of a new movement of abstract art that went global, and to the politics of non-objective art that defined the Cold War era. Born in Brazil in 1928 to Lebanese parents, Achkar and her family moved to Beirut when she was ten years old. In 1947, she was one of the first students to enroll at Beirut's newly opened Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts, where her classmates included artists Shafic Abboud and Jean Khalifé, who would become fellow luminaries in Lebanon's art world. She was taught by Italian painter Fernando Manetti and French painter Georges Cyr, who were both prominent figures in the development of modern art in Lebanon.

Achkar would be one of the last abstract painters in Lebanon and the wider region whose work was directly connected to the turbulent history of 20th-century European abstraction.

- Arie Amaya-Akkermans

Like Abboud and many of the other most distinguished Lebanese artists of the 20th century, such as Omar Onsi, Moustafa Farroukh and Elie Kanaan, Achkar would spend formative years in Paris during the decade following the end of World War II. Paris was bustling with emigré artists from the Global South, who would later bring different schools and styles of abstraction back home, inaugurating rich, hybrid traditions that in many cases would be difficult to trace back to the source.

Indeed, the political history of abstract art in the Arab world is hard to codify. Many partial explanations for abstraction emerged under the influence of Arab nationalism, arguing for a kind of nativist understanding that drew on everything from Islamic art to Byzantine icons to medieval Arab mathematics. But these interpretations, while rightly opposed to the traditional Eurocentric view that all abstraction comes from the West, operate under a misunderstanding between abstract painting as a modern art movement and abstraction in any form of representational art—a cultural and anthropological process across history, going all the way back to the prehistoric art of the Ice Age, when early modern humans discovered symbolic forms. The latter abstraction wasn't invented in the Europe of the 20th century, but it also didn't emerge in the Islamic Golden Age. In other words, the argument over when abstract art really emerged misses the point because abstraction is not a historical period, but an ongoing process.

Nevertheless, the iconography of modern art encouraged both the Eurocentric and the Arab nationalist and nativist interpretations. Many Lebanese artists heavily influenced by Cubists like Jean Metzinger and Fernand Léger would return home and develop reinterpretations of regional traditions, set against European templates. In the case of Achkar, this oversimplification wasn't possible. She painted in Cubist style for a short period, before moving on to develop her highly personal style around 1970, characterized by long and irregular stripes of vibrant colors in the manner of European Expressionism, but in a painterly atmosphere closer to American Color Field painting.

In my mind, it is the only serious attempt by any artist anywhere to build on the early foundations of Synthetic Cubism laid by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso in 1912-1913. In the 1910s, Braque and Picasso invented the revolutionary technique of papiér collé, using large stripes of paper interlocked in a painting, to produce the effect of a non-objective space, abolishing the representation of objects altogether. But Braque, whom Achkar always mentioned as a central influence, and Picasso both quickly moved on from this foundational period of their art (in his later years, Braque returned to semi-figurative Cubism, while Picasso devoted himself to Surrealism).

Achkar's mature paintings are an attempt to apply Synthetic Cubism to the already deconstructed color field. "It is like layers of paper placed on top of each other in quantity, you tear them off one by one, to arrive at the primordial which is the self," she said in 1989, in her typically enigmatic way, of her painting process and, perhaps, as a hint of her devotion to Synthetic Cubism. "Remove everything that is superficial to arrive at the center, and the center is once again, the notion of a circle, that is to say life, and fear will say death."

The rise of formal abstraction in Paris in the 1950s, both in its expressionist and minimalist versions, and its subsequent journeys to the postcolonial world, however, weren't simply the triumph of the avant-garde over academic realism or impressionism. It was in large part due to the cultural imperialism of the United States during the Cold War, spearheaded by the Museum of Modern Art, and in Paris, specifically, by the art initiatives of the Marshall Plan. This part of the Marshall Plan's aim wasn't simply to make a case for American cultural hegemony through influential traveling exhibitions, but to counter the growing influence of Soviet Socialist Realism, including in the Middle East. In parallel to the "School of Paris," an umbrella term in many Global South countries for home-grown abstract expressionist movements that trained in Parisian studios between 1950 and 1980, many influential artists from Syria, Lebanon and Iraq were trained in the Soviet Union.

In spite of her own silence—and being overlooked by much of the art world—Achkar still has so much to say about art and the turbulent 20th century

- Arie Amaya-Akkermans

But the internal conception of abstraction as a challenge to representational art was much more ambitious than the Cold War gave it credit for. Abstract painting gained a new life in the peripheries of the West, not only as a tool to bypass censorship, but also as a cosmopolitan language beyond the borders of Europe. An entire generation of women painters rose in Lebanon—from Yvette Achkar to Helen Khal, Etel Adnan and Nadia Saikali, the only surviving painter of this generation—who never abandoned that cosmopolitanism. For all its mysterious opacity, within Achkar's work was an uncompromising and life-long storytelling of Lebanon's own tragic fate. Achkar lived in Lebanon throughout the cruel years of the Lebanese Civil War, continuing to paint. In the 1980s, her iconic pastel tones turned to dark reds and blacks, surrounding a frightening emptiness.

By then, global abstraction had lost its political power as a counterweight of Socialist Realism, which was also moribund in the waning years of the Cold War. For many more decades, even though she kept producing compelling new work in Lebanon, Achkar was never the subject of a monograph or an institutional exhibition. She has been bypassed in major shows devoted to prominent women in abstraction, such as MoMA's "Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction," in 2017—a glaring omission from a show about artists who had "sought an international language that might transcend national and regional narratives." She was also not included in a major exhibition last year at London's Whitechapel Gallery, "Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970," which billed itself as promoting "an overlooked generation" of 80 artists from around the world. Her inclusion in the traveling exhibition "Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World 1950s-1980s," organized by Sharjah's Barjeel Foundation beginning in 2020, was a small step in the right direction.

In an interview with L'Orient-Le Jour in Beirut in 2018, she described painting as "a delicious moment, when you're alone listening to yourself." In spite of her own silence—and being overlooked by much of the art world—Achkar still has so much to say about art and the turbulent 20th century. Her work should speak into the future, a reminder of chaotic and uncertain times, like our own.