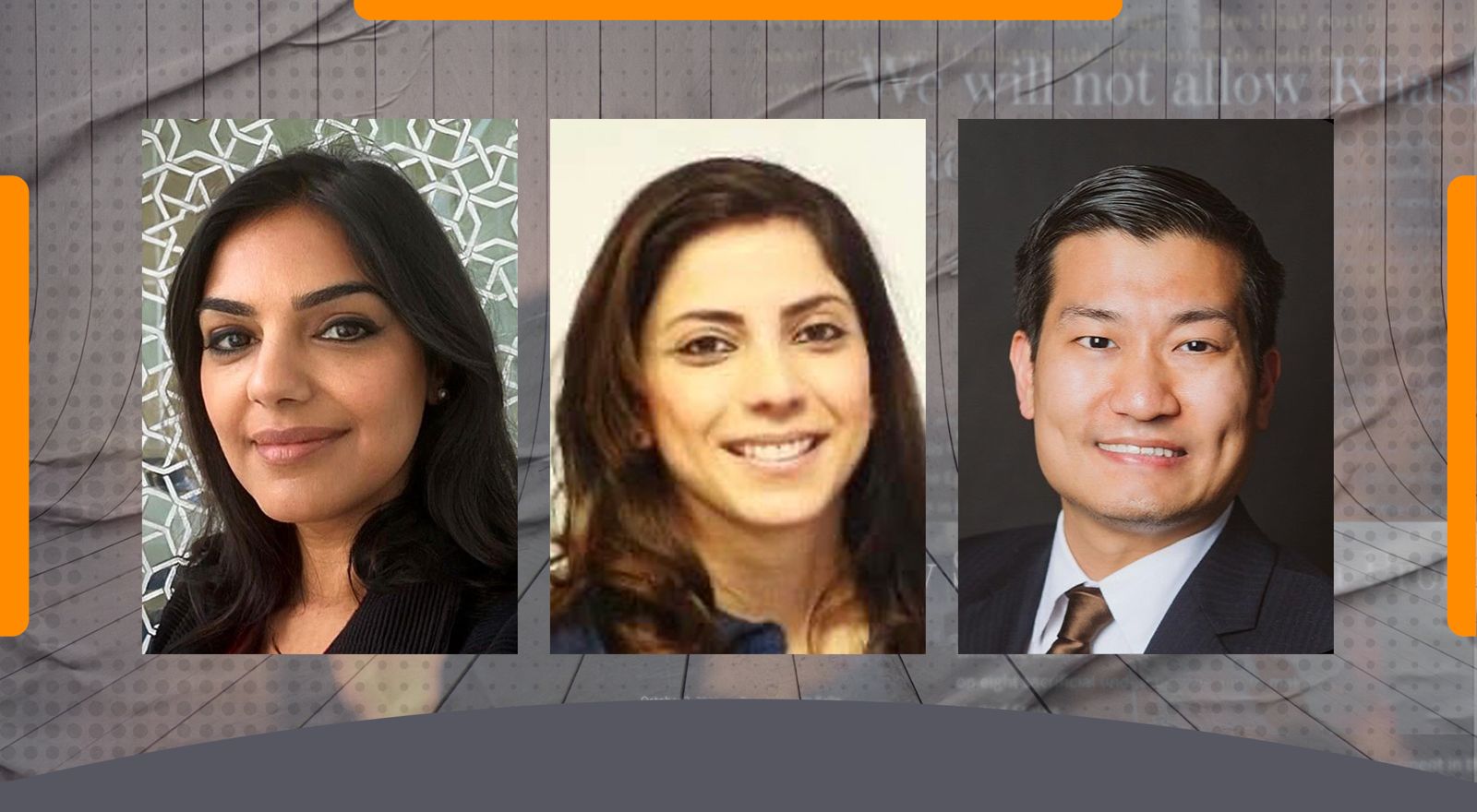

Dalia Fahmy is an associate professor of political science at Long Island University and a visiting scholar at the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights at Rutgers University. She is also a non-resident fellow at DAWN.

The brutal deaths of Mahsa Amini last year at the hands of Iran's morality police and of Neda Agha-Soltan during Iran's Green Revolution 13 years earlier reflect a pattern of violent political repression throughout the Middle East specifically targeting women. When authoritarian regimes are confronted with public protest and social unrest, they often respond by violently attacking women. This gendered nature of authoritarian violence is seen as an effective form of social control for two reasons: It aims to render normally patriarchal societies impotent in defense of their female family members and to create a subclass in women who are seen as suspect citizens rather than agents of change.

For years, especially under President Hassan Rouhani, there was a fragile equilibrium in Iran over the mandatory wearing of the hijab. Women covered themselves in public, often with a loosely draped scarf. In the more affluent northern districts of Tehran and some residential areas in other cities, women even wore their scarves casually over their shoulders. By and large, they were allowed to exercise this freedom without undue interference from the authorities. But Rouhani's hard-line successor, Ebrahim Raisi, ended any such leniency, calling for the strict enforcement of the hijab law and warning that "the enemies of Iran and Islam" were targeting the "religious foundations and values of the society." Suddenly, the morality police—the Gasht-e Ershad or Guidance Patrol—resurfaced, zealously attempting to impose strict hijab standards on the streets.

It was this ill-considered decree from Raisi that triggered Amini's arrest for a perceived dress code violation, her subsequent abuse and death while in custody, and the eruption of widespread protests. It was the sign of an out-of-touch regime that believed it could no longer tolerate even the slightest hint of opposition or dissent.

When authoritarian regimes are confronted with public protest and social unrest, they often respond by violently attacking women.

- Dalia Fahmy

The regime may have believed that it could swiftly quell these demonstrations, as it had before, as Iranians have protested against the skyrocketing cost of living, unpaid wages and electoral irregularities over the past several years. On each occasion, riot police were promptly dispatched, leading to a cycle of arrests and repression. The crowds eventually dispersed, and the protests subsided.

Of course, after Amini's death last year, the regime underestimated the tenacity of the demonstrators and the enduring resonance of their rallying cry: "Woman, Life, Freedom!" The protesters' demands extended beyond mere economic grievances, encompassing demands for fundamental rights for women and an impassioned call to transform Iran and reclaim individual freedoms that have long been stifled under the Islamic Republic.

Many protesters still rallied around the memory of Neda Agha-Soltan, who became a symbol of the Green Revolution in 2009. She was killed in Tehran, shot in the upper chest as she stood outside her car on the edge of a protest following Iran's disputed presidential election. Like Raisi, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had also pledged to strictly enforce previously loosened restrictions on the hijab. During the months of mass protests in 2009, thousands of women were arrested or intimidated because they did not adhere precisely to a rigid Islamic dress code in public. This has been the lasting image of Iran's waves of protests since 2009: police and security forces attacking women, symbolized by the fate of both Agha-Soltan and Amini.

State-gendered violence should be acknowledged for what it is: an assault on the core principles of freedom, equality and human rights, and the key to the endurance of these regimes.

- Dalia Fahmy

This pattern of gendered state violence extends throughout the region. On the eve of Egypt's popular uprising in 2011, 24-year-old Asmaa Mahfouz—one of the founders of the April 6 youth movement—posted a video on YouTube calling on Egyptians to take to Cairo's Tahrir Square on Jan. 25 to reclaim their honor and dignity. Mahfouz's video has been credited with helping spark the Egyptian uprising that ended the 30-year reign of President Hosni Mubarak. The simple chant of "one hand!"—that all Egyptians should unite for a democratic Egypt—was to usher in a new era for women, or so they hoped.

Instead, the uprising has led to nearly 13 years of contentious politics and a new dictatorship under Abdel Fattah al-Sisi for the past decade. The very group instrumental for the uprising's initial success—women—have been marginalized ever since. In Tahrir Square, it seemed during those 18 days, women were finally equal with men, which showed that the culture of fear in Egypt toward the state was ending. The state responded with appalling violence toward women, many of whom were beaten and sexually assaulted by the security forces—not only during the uprising, but after Mubarak's fall, when Egypt's generals assumed power. This still reverberates in Egypt under Sisi today.

In Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, activist and political prisoner Loujain al-Hathloul, who led the campaign to end the ban on women driving in the kingdom, is still living under a travel ban. After she was effectively kidnapped from the United Arab Emirates in 2018 and forcibly returned to Saudi Arabia, she was sentenced to prison in 2020 under a sweeping counterterrorism law. Since released but unable to leave Saudi Arabia, she has continued to be vocal about the torture she and other women were subjected to in prison for their activism. So much for Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman "liberating" or "empowering" Saudi women.

All these examples underscore the striking parallel between male coercion within patriarchal societies and authoritarian state power structures in the region. In both cases, dissenters are ruthlessly silenced, and perpetrators enjoy a disturbing level of impunity. This creates a divisive hierarchy, where men are placed above women, and the state reigns supreme over all. These are not just a series of isolated incidents but a calculated strategy employed by autocratic and absolute rulers, who deliberately stoke the flames of intolerance and misogyny by singling out women in public life as a means of exerting ultimate social control. The common thread here is the deliberate targeting of women as a means of consolidating power. By undermining gender equality, authoritarians are not only suppressing half their population but also weakening the very foundations of their societies.

This strategy is as old as authoritarianism itself. Dictators are adept at using fear to divide and distract, and so they exploit patriarchy. Since state-gendered violence is an effective tool in ultimate social control, the murders of protesters, activists and women who are symbols of change, like Neda Agha-Soltan and Mahsa Amini in Iran, will continue as long as authoritarian regimes continue to thrive in the region. State-gendered violence should be acknowledged for what it is: an assault on the core principles of freedom, equality and human rights, and the key to the endurance of these regimes.