A DAWN Briefing Paper

Summary

On December 17, 2021, Saudi Arabia's Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) unveiled a master development plan for the Jeddah Central Project. Previously known as New Jeddah Downtown, the Jeddah Central Project is part of MBS' ambitious Vision 2030 plan. The Jeddah Central Project envisions demolishing existing neighborhoods of south Jeddah to transform it from a series of middle-class and working-class neighborhoods into a luxurious stretch of high-cost homes, upscale restaurants, and public venues to attract wealthy Saudis and expatriates. While the government is projected to spend over $20 billion on the high-end development project, it has seemingly allocated very little to compensate the 1.5 million Saudis who have lost or will lose their homes, livelihoods, and neighborhoods to the demolitions.

Demolitions began slowly in October 2021, but by December, Saudi authorities started demolishing large parts of several neighborhoods, forcibly evicting residents with very little notice and without consulting them in advance or providing them adequate compensation afterwards. Between October 2021 and May 2022, Saudi authorities demolished between 16 and 20 neighborhoods across 4,000 square kilometers. The speed and breadth of demolitions within Jeddah has been unprecedented in modern Saudi history, and the impact of these demolitions on Saudi citizens will be significant. A recently published map of the project shows that these demolitions, which are expected to be completed next month, will affect 1.5 million Saudis in 63 neighborhoods spread across 3 million square kilometers.

DAWN's research has found that the Saudi government's forced evictions violate international law, as these actions do not comply with internationally recognized legal safeguards to ensure and protect the rights of residents. The Saudi government has failed to exhaust proper alternatives to the evictions; follow due process, including providing advance notice and an opportunity to appeal; or offer prompt, adequate, and effective compensation. Further, the forced evictions also violate Saudi law, particularly the Law of Expropriation of Real Estate, which requires the government to exhaust all alternatives to expropriation, including for eminent domain, and provide fair compensation and appropriate and reasonable notice.

This briefing paper examines the Jeddah demolitions (هدم جدة) by providing a detailed chronology of the neighborhood demolitions and forced evictions, the international and Saudi legal framework governing these acts, and evidence demonstrating that the Saudi government failed to comply with its international and Saudi legal obligations in connection with its exercise of eminent domain in Jeddah. It relies on the testimony of five Saudi families affected by the government's actions, as well as government documents, videos and pictures shared with DAWN researchers, satellite imagery within the public domain, and published media articles. It also provides recommendations to the Saudi government and international and regional organizations to address the human rights violations and legal harms that many Saudi families affected by these demolitions and evictions have endured.

Recommendations

Saudi Arabian Government

- The Saudi government should provide adequate compensation to all residents whose homes, businesses, and property were damaged or destroyed, including paying full market price for all damaged or demolished buildings, both to Saudi citizens and to foreign nationals whose property it damaged, destroyed, or left uninhabitable.

- The Saudi government should cease all demolitions in and around Jeddah until it can ensure that development projects will adhere to international legal standards and Saudi law, including providing sufficient notice, an opportunity to appeal the decision, and prompt and adequate compensation for property.

- When providing compensation, the Saudi government should assess the value of property before demolition and ensure payment occurs within 60 days, as required by Saudi law.

International and Regional Organizations

- UN Habitat and the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing should investigate these forced evictions and conduct interviews with residents and former residents of these neighborhoods to establish an accurate factual record to assist those evicted receive adequate compensation, resettlement assistance, and support services.

- UN Habitat and the Special Rapporteur should collect information to inform the UN and its relevant country and regional offices of these forced evictions to develop policies to address and mitigate these harms.

- UN Habitat's Saudi Arabia office, which has $25 million worth of projects in 17 Saudi cities under a joint-development program with the Saudi Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, should suspend these projects until the Saudi government provides adequate compensation and resettlement support to those evicted and ensures that future development projects will adhere to international standards and best practices.

The negative public perception of the Jeddah demolitions are informed by earlier government actions, where Saudi officials used the pretext of public safety and development to target the country's minority Shia population, deploying military forces to destroy the 400-year-old Almosawarra neighborhood in the town of Awamiya in the Eastern Province in June 2017.

Background

Jeddah is the second largest city in Saudi Arabia with a population of about 4.5 million people. While a major center of trade, commerce, and culture, including a UNESCO-protected historical quarter, Jeddah also features socioeconomic inequality, an overcrowded urban center, and a shortage of housing for low- and even middle-class Saudis.

In October 2021, Saudi authorities began to demolish thousands of homes throughout numerous neighborhoods in south Jeddah as part of the plan to redevelop the area as part of the Jeddah Central Project. While public criticism of the Saudi government is rare and scarcely tolerated, Saudi citizens nonetheless demonstrated on various dates in February 2022 against these demolitions and forced evictions, which occurred predominantly in densely-populated neighborhoods including several working-class neighborhoods Saudi officials consider slums.

The need to improve and develop parts of Jeddah, especially within its underdeveloped south section, is a longstanding issue for the Saudi government. For years, city planners and government officials drafted different plans and projects, and while most remained little more than speculative possibilities, the government did implement some of these projects. Government bureaucracy and corruption contributed to low levels of implementation.

Although demolitions began in October, the government did not fully unveil the plan underlying these demolitions, the Jeddah Central Project, until mid-December 2021. The Jeddah Central Project, which forms part of MBS' ambitious Vision 2030 plan, envisions demolishing existing neighborhoods of south Jeddah to transform them into a luxurious stretch of high-cost homes, upscale restaurants, and public venues.

The speed and breadth of evictions and subsequent demolitions are unprecedented in modern Saudi history. The impact of these demolitions on Saudi citizens and foreign nationals, especially economic migrants, living and working in these neighborhoods has already been significant and will continue to be so. A recently published map of the project shows that these demolitions will affect as many as 1.5 million residents—about one-third of the city's population—across 63 neighborhoods. Saudi authorities plan to complete the demolitions by October 2022.

The negative public perception of the Jeddah demolitions are informed by earlier government actions, where Saudi officials used the pretext of public safety and development to target the country's minority Shia population, deploying military forces to destroy the 400-year-old Almosawarra neighborhood in the town of Awamiya in the Eastern Province in June 2017. In carrying out these acts, government forces killed at least twenty people and displaced thousands.

Bulldozers demolish buildings on March 14, 2022, as part of a $20 billion clearance and construction government project that stands to displace half-a-million people in Saudi Arabia's second city Jeddah. - The demolitions risk fuelling anti-government sentiment in the 30-plus neighbourhoods that have been targeted, many of which housed a mix of Saudis and foreigners from other Arab countries and Asia. Evicted residents had been living in the homes for up to 60 years, said ALan NGO. Some were driven out when their power and water was cut off, or threatened with jail for disobeying an eviction order, it added.

Source:AFP via Getty Images

In Almosawarra, Saudi authorities did not consult with residents beforehand and refused to offer adequate compensation afterwards. Before moving to destroy the neighborhood of about 30,000 people, the Saudi government cut electricity and prohibited the provision of aid to residents. It then deployed military forces to destroy the neighborhood. While effectively an attack against the country's minority Shia community, the government justified these actions as necessary for development, security, and to prevent terrorism, offering unfounded rationales such as the need to remove narrow Ottoman era streets and alleys that afforded terrorists "hiding spots."

Later the same year, in October, MBS announced his vision for Neom, a $500 billion high-tech city to be populated by tourists from around the world, tech companies and start-ups, and wealthy international investors. The planned 10,230-square-mile city—33 times the size of New York City—is a cornerstone of the Vision 2030 plan to diversify the Saudi economy away from its reliance on oil revenues. When construction began a few years later, in 2020, Saudi authorities displaced the entire Huwaitat tribe, which lived in Tabuk, a northwestern province. For hundreds of years, the tribe had occupied villages and towns, including a historical capital, Khuraybah, across the province. There is no evidence that the eviction of the Huwaitat tribe was a last resort as the law requires, nor is there any evidence that government officials offered adequate compensation for their land and personal property.

The Saudi government has presented the same types of arguments to justify the demolition and reconstruction of Jeddah's old neighborhoods. The government announced that these neighborhoods harbor outlaws and used dehumanizing language to refer to these neighborhoods' residents by referring to them as "illegal migrants," "drug dealers," and "criminals." The government also claimed Saudi citizens who are residents of Jeddah's demolished neighborhoods requested these demolitions so that their neighborhoods would be "cleaned" of such people.

For the Jeddah Central Project, the Saudi government also presented an economic rationale for demolishing these neighborhoods. According to Saudi authorities, this project, valued at 75 billion Saudi riyals ($20 billion), will develop 5.7 million square meters (61 million square feet) of land overlooking the Red Sea. It will include rebuilding more than 17,000 residential units and replacing many of the existing neighborhoods with an opera house, an oceanarium, a sports stadium, a marina, and a public beach. Saudi authorities expect that the project will add an additional 47 billion Saudi riyals ($12.5 billion) to the country's economy by 2030. Saudi officials cite similar economic development rationals when justifying the Neom project.

Methodology

DAWN researchers relied both on publicly available information and on private interviews they conducted with residents of the affected neighborhoods in Jeddah. Publicly available information included UN Habitat studies, academic research, government documents, and media reports.

Between January and June 2022, DAWN researchers spoke to members of five families affected by these demolitions. DAWN wrote to the Jeddah Municipality and to the state-sponsored Saudi Human Rights Commission on October 7, 2022 for comment, but did not receive a response. Private interviews with individuals of the affected neighborhoods include current residents, residents recently displaced by the Jeddah demolitions, and past residents. DAWN conducted numerous interviews on background, but few individuals were willing to provide information even as unnamed sources due to the considerable security risks. As one individual from Jeddah replied to a DAWN researcher on February 20, 2022: "I am honored, but engaging with the media under MBS is considered treason and [leads to] execution."

The following interviews are cited specifically within this briefing paper.

- Source A: Interview on March 2, 2022 and March 5, 2022. Source A was a previous resident of the al-Kandara neighborhood. Saudi authorities evicted Source A and demolished Source A's house during the last week of January 2022.

- Source B: Interview on January 18, 2022 and January 28, 2022. Source B was a resident of the Alhindawaya neighborhood.

- Source C: Interview on January 18, 2022 and January 28, 2022. Source C was a previous resident of the Alhindawaya neighborhood.

- Source D: Interview on March 16, 2022. Source D was a previous resident of the Alkarantina neighborhood.

- Source E: Interview on March 4, 2022 and March 5, 2022. Source E is a resident of the Alazizia Sha'biyyah neighborhood.

DAWN does not disclose the identity of its sources to protect the privacy and security of these individuals.

Chronology

In October 2021, residents of south Jeddah reported their surprise at seeing the word "eviction" spray painted on their homes and businesses. About a month later, in November 2021, Saleh Al-Turki, the mayor of Jeddah, announced that the city had "completed a draft scheme to develop slums in 32 neighborhoods" covering an area of over 214 million square meters (2.3 billion square feet). For comparison, 214 million square meters is about 82.6 square miles, while the entire city of Washington, DC is only 68.3 square miles. On December 17, 2021, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) announced a master plan for what he called the Jeddah Central Project as part of his Vision 2030.

Saudi authorities began demolishing large neighborhoods in Jeddah in December 2021, forcibly evicting residents without consulting them in advance, providing them adequate compensation afterwards, or taking their welfare into consideration. While the demolitions began in October, the bulk of the demolitions occurred from December 2021 through May 2022, destroying between 16 and 20 neighborhoods.

The first two Jeddah neighborhoods the Saudi authorities demolished were Ghulail (39,785 residents) and Petromin (30,044 residents) on October 23, 2021. According to the Jeddah Municipality, the nearly 70,000 residents of these neighborhoods received notification of the demolition on the same day that the demolitions began. The Saudi government also turned off the electricity and shut down other critical services for these neighborhoods on this day.

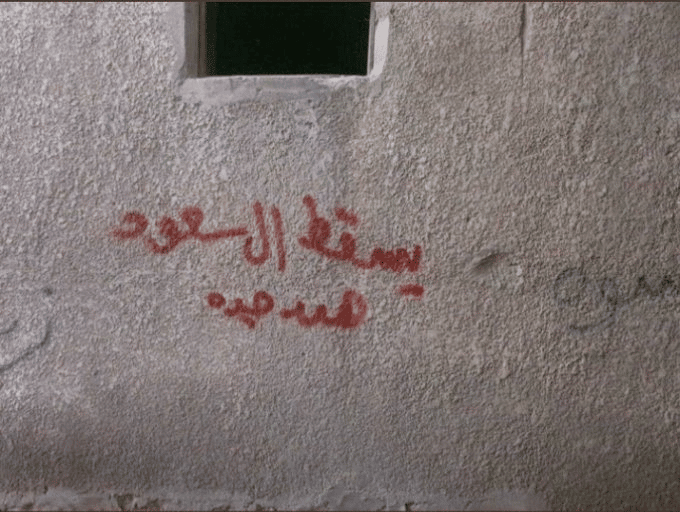

The next round of neighborhood demolitions occurred in December 2021, when the Saudi government razed the the following neighborhoods: Alqurayyat (10,850 residents) on December 6, Alkarantina (200,000 residents) on December 13, Alnuzla Alyamaniyah 1 (49,210 residents) on December 20, and Althaalba (10,745 residents) on December 27. In each instance, the Saudi government turned off the neighborhood's electricity two days before the demolitions began on December 4, 11, 18, and 25 respectively. Saudi authorities claimed that neighborhood residents received notification of the impending demolitions on November 1, but neighborhood residents countered this claim and insisted that they did not receive direct notification from the government and that the only notification that the government provided was the spray painting of "eviction" on their homes, businesses, and other neighborhood buildings. Many residents took to Twitter to complain that they were not provided alternative housing or compensation for their destroyed homes and businesses.

The third round of demolitions began on January 15, 2022, and included the Albalad neighborhood (50,715 residents) and Alsaheefa neighborhood (22,988 residents). The Saudi government claimed that neighborhood residents received notification on December 25, 2021, and that it turned off electricity and other basic services on January 8. Source E claimed that the government did not notify them directly and that the only notification they received was through the spray painting of the word "eviction" on their home and business. Source E also confirmed that they did not receive alternative housing or compensation.

The fourth round of demolitions began on January 29, 2022, and included the following neighborhoods: Alammariyah (11,579 residents), Alkandarah (29,973 residents), Alsabeel (23,974 residents), and Alhindawaya (44,385 residents). According to the Saudi government, neighborhood residents received notification on January 8, 2022, and the government turned off electricity and other basic services on January 22, 2022. Again, neighborhood residents claimed that the government did not provide direct notification and that the only notification they received was through the spray painting of "eviction" on their homes and businesses. Residents also said that they did not receive alternative housing or compensation.

The fifth round of demolitions began on February 12, 2022 and included Alnuzla Alyamaniyah 2 and 3 neighborhoods (49,210 residents) and Althaghr neighborhood (16,674 residents). The Saudi government claimed that it notified the residents on January 22, and turned off electricity and other services on February 5. Neighborhood residents again claimed that they did not receive notification other than the spray painting of "eviction" on their homes and businesses. Residents also reported that they were not provided alternative housing or compensation.

The sixth round of demolitions began on February 26 and included the Albaghdadiya neighborhood (19,930 residents) and Alsharqiyah neighborhood (19,235 residents). The Saudi government claimed it provided notification to residents on February 5, and that it turned off electricity and other services on February 19. Source A claimed that they did not receive notification other than the spray painting of "eviction" on their home and business, and nor did they receive alternative housing or compensation.

The seventh round of demolitions began on March 12 and included the Alnuzla neighborhood (7,973 residents), Alsalama neighborhood (2,345 residents), and Mada'en Alfahd 2 neighborhood (29,057 residents). The Saudi government claimed that it provided notification to these residents on February 19, and turned off electricity and other services on March 5. Source A confirmed that neighbor residents did not receive notification other than the spray painting of "eviction" on their homes and businesses and that they did not receive alternative housing or compensation.

The Jeddah demolitions resulted in forced evictions that violated international law. Relevant international legal provisions required the Saudi government to follow appropriate measures to ensure and protect the rights of residents, to exhaust proper alternatives, follow due process, and offer prompt, adequate, and effective compensation.

Forced Evictions under International Law

According the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, forced evictions constitute a gross violation of human rights including the right to life, the right to freedom from cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment, the right to security of the person, and the right to non-interference with privacy, home, and family found within the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Forced evictions violate the right to an adequate standard of living, including the right to adequate housing, food, water, and sanitation, and the right to health found within the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Forced evictions also violate the right to property found within the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on Development-Based Evictions and Displacement (Basic Principles) also provide important legal safeguards. The Basic Principles reaffirm the legal obligation of states to refrain from forced evictions under existing international law (paragraph 1) and state that evictions should not render individuals homeless (paragraph 43). Before evictions, the government should provide "appropriate notice to all potentially affected persons" (paragraph 37), and that after eviction, the government must provide "just compensation and sufficient alternative accommodation" immediately and without discrimiantion (paragraph 52).

UN Habitat defines a forced eviction as "the permanent or temporary removal against their will of individuals, families and/or communities from the homes and/or land which they occupy, without the provision of, and access to, appropriate forms of legal or other protection." It also outlines several elements that individually, or combination, help to define a forced eviction. These elements are:

- A permanent or temporary removal from housing, land, or both;

- The removal is carried out against the will of the occupants, with or without the use of force;

- It can be carried out without the provision of proper alternative housing and relocation, adequate compensation and/or access to productive land, when appropriate;

- It is carried out without the possibility of challenging either the decision or the process of eviction, without due process and disregarding the State's national and international obligations.

Policy Considerations

Forced evictions have a serious and long-term negative impact on people, especially the poor and other vulnerable populations, including those living in informal housing. They cause the loss not only of peoples' homes, but also the loss of neighborhoods, social bonds, and material possessions. Often, they result in the removal of access to vital services and sources of livelihoods. Forced evictions have a disproportionate impact on women, and combined with existing discrimination, they further disadvantage women and challenge their ability to own and inherit property. Forced evictions also can lead to increased risks of physical harm, again especially for women, due to homelessness and the loss of support and services.

Forced Evictions in Jeddah

The demolitions and the removal of residents from Jeddah's neighborhoods constitute forced evictions because they entail the removal of occupants against their will, while the government has failed to provide alternative housing, adequate compensation, or the possibility of challenging the government's decision.

From DAWN's interviews and other publicly available information, it is clear that many occupants did not wish to leave their neighborhoods. Sources A, B, and D agreed that some of these neighborhoods were underdeveloped and in need of government services, but they said a gradual reconstruction or development would have been the appropriate remedy, not mass demolitions and hasty evictions with almost no notice.

Sources A, B, C, D and E, in addition to other Saudis that spoke online, confirmed that they were not consulted about their removal, or any other aspects of the government's development plans, such as what constitutes appropriate compensation or relocation.

Sources A, B, and C said that the government ordered them to leave their buildings within 48 hours without consideration of their ability to do so within that period or the availability of alternative housing. Source E told DAWN that their building was marked for demolition six days before the government switched off electricity, forcing them to leave. Source D told DAWN that they found out of their impending removal when government employees marked their buildings for demolition and that they did not receive any direct contact or communication from Saudi government officials.

According to DAWN's interviews and publicly available information, the Saudi government has provided very little temporary or permanent housing for those they forcibly evicted. On January 31, 2022, the government announced that it had provided new housing facilities to 550 families whose homes had been demolished. It also reported that an additional 4,781 housing units would be ready for evicted families by the end of 2022, a tiny fraction of the replacement housing needed for the number of units destroyed. Later, in August 2022, the Saudi government announced that it would provide temporary housing and one year of rent for 14,156 families, while providing another 86,000 with unspecified services, food, water, and medicine. These provisions appear to provide basic protections for only about 5.7 percent of the estimated 1.5 million impacted residents.

Likewise, the Saudi government has provided very limited compensation to forcibly evicted families. In mid-February, the government began a process for forcibly evicted residents to collect compensation based on existing land deeds, while claiming that only 10 to 15 percent of the razed buildings were legally owned, thus setting the stage for very few evicted families to receive compensation. More recently, in June, the Saudi government announced that it would send checks totaling 1 billion Saudi riyals ($266 million) to forcibly evicted families. On June 6, Jeddah Mayor Saleh al-Turki confirmed this announcement, and said that the government had issued 1 billion Saudi riyals ($266 million) to compensate forcibly evicted families in the affected neighborhoods. The Saudi state-controlled television station al-Ekhbariya also interviewed one previous resident of the Ghulail neighborhood who said he was given just compensation after his neighborhood was demolished in October 2021.

While welcome developments, this temporary housing and limited compensation will only address a fraction of those evicted and does not meet international standards or Saudi legal requirements for notice or compensation. Moreover, foreign nationals, who make-up a significant portion of those affected, will not receive any compensation.

Government Violations of Saudi Law

In addition to violating international human rights law, the Saudi government violated Saudi law by forcibly evicting occupants in the manner that it did. The government violated several articles of the 2003 Law of Expropriation of Real Estate (Expropriation Law), which is the controlling legislation for evictions in Saudi Arabia.

Article 24 of the Expropriation Law provides individuals with the right to challenge an eviction decision within 60 days of the issuance of the decision. Sources A, B, C, D, and E told DAWN that the Saudi government did not inform them of the date of its decision to demolish their homes and evict them, and so they were unable to challenge the decision in court. This inability to legally challenge these decisions seems to constitute a pattern. For example, according to Source B, in January 2022, residents of Hayy al-Jame`a neighborhood attempted to meet with Khalid al-Faisal, the Governor of Mecca, whose jurisdiction includes Jeddah, but officials at the governorate turned them away and refused to engage on the matter.

Article 1 of the Expropriation Law requires the government to demonstrate that there is no alternative to evicting people from their homes. Based on all available public reporting, as well as DAWN's interviews with Jeddah residents, it does not appear that the government took the necessary steps to conclude that there was no alternative to these forced evictions. Even if such deliberations did occur, the government did not communicate them to affected Jeddah residents or make them publicly available in a reasonable manner. It is also unclear whether the government considered using available public lands to develop the entertainment venues and other projects that it proposed in these demolished residential neighborhoods.

Article 8 of the Expropriation Law stipulates that the government must offer compensation to an evicted resident within 90 days of approving an eviction, while Article 17 requires that residents be granted at least a 30-day notice before eviction. Again, according to the Jeddah residents that DAWN interviewed and public reporting, this has not happened, and in some cases, several months have passed since the evictions.

In sum, all available information and DAWN's interviews suggests that the Saudi government acted with complete disregard to the basic rights and well-being of Jeddah residents affected by these demolitions. While the government evicted Saudis and foreign nationals of various socioeconomic backgrounds from the demolished Jeddah neighborhoods, the poorest residents of Jeddah have suffered disproportionately. In fact, the Saudi authorities insisted that the demolished neighborhoods were underdeveloped (`ashwaee), had become centers of illegal activities such as drug trafficking, and were populated by illegal migrants. By the government's own admission, these neighborhoods and their residents were poor and marginalized. The government used this justification to legitimize its unlawful forced evictions, even though some of the demolished neighborhoods were relatively developed and were not considered slums.

Conclusion

The Jeddah demolitions resulted in forced evictions that violated international law. Relevant international legal provisions required the Saudi government to follow appropriate measures to ensure and protect the rights of residents, to exhaust proper alternatives, follow due process, and offer prompt, adequate, and effective compensation. According to the sources that DAWN interviewed, on background and specifically for this paper, as well as publicly available information and other reporting and documentation, the Saudi government failed to comply with all of these requirements.

These forced evictions also violate Saudi Law, particularly the 2003 Law of Expropriation of Real Estate, which requires the government to demonstrate there was no alternative to expropriating these lands, and that the government first exhausted the possibility of using state land to complete these projects before considering private property. The law also requires Saudi officials complete a specific assessment of the property to award compensation 60 days after the government approves the project. Saudi citizens must receive 60 days notice and if expropriation occurs, government compensation must be fair. Based on all public reporting and DAWN's multiple interviews, the government failed to meet any of these legal requirements.