Juan Cole is the Richard P. Mitchell Collegiate Professor of History at the University of Michigan. He is also a non-resident fellow at DAWN and a non-resident fellow at the Center for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies in Doha.

In 1917, the British Cabinet had been convinced by London Zionists, proponents of turning Judaism into a form of nationalism that sought to colonize a territory, to issue the Balfour Declaration to Lord Rothschild. "His Majesty's Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people," the declaration stated, "and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country." It was a ridiculous pledge, since no such home for the Jewish people (even if the British then thought about it more as a community center than a new nation-state) could have avoided injuring the rights of the indigenous Palestinians.

The British rulers of hundreds of millions of Asians and Africans thought nothing about moving people around to suit their imperial interests, and even at one point considered transporting millions of Punjabis to Iraq to relieve what they saw as India's dangerous population pressure. In 1915, two years before the tragic Balfour Declaration, 683,389 Arabic-speaking natives dwelled in the territory that the British would call Palestine, about 81,000 of them Christians and the rest Muslims. There were only 38,752 Jews, most of them recent immigrants from Russia and Europe permitted to come into these provinces by the Ottoman sultan, some as pilgrims or retirees.

The British in Palestine created a province of Gaza, separating it from the Bedouin-dominated area of Beersheba and the Negev, and permitted its notable families to administer it, though some refused to cooperate with the foreigners and others were distracted by local clan-based political faction-fighting. The war-time food crisis passed, probably helped more by the "highly fertile" land of Gaza than by laissez-faire British economic policies. Still, growing landlessness and poverty kept much of the population on the edge.

The influx of Jewish immigrants into Palestine, whom the indigenous viewed as illegal aliens sponsored by an illegitimate colonialism, created tensions. People in Gaza, as in the rest of Palestine, demonstrated annually against the Balfour Declaration. The Jews who colonized Palestine (their words) established a Jewish National Fund to buy land, which it forbade ever after to be sold to a non-Jew. The Palestinian population, in a largely agricultural country, doubled from 1915 to 1947, with multiple children splitting up the family farm in each generation, which had the effect of turning many Palestinian proprietors into very small farmers or landless laborers. At the same time, Jewish immigrants took 6 percent of the best land off the market. A riot against Jews in 1928 in Jerusalem had echoes in Gaza, where the 54 Jews who lived there were threatened by a mob. The former mayor, Said Shawa, and his clan intervened to protect the Jews.

Some mayors in the 1930s, as historian Jean-Pierre Filiu details in his book Gaza: A History, undertook improvements, establishing a new hospital, a park and a fancy neighborhood near the beach. Filiu says that the French tourist magazine, Le Guide Bleu, in 1932 praised Gaza City's lively markets, its antiquities such as the ancient mosque, and its good communications, since it lay on the rail link from Haifa to the Suez Canal. It put Gaza City's population at 17,480, more than four times larger than Khan Younis. Deir al-Balah and Rafah were small.

A French tourist magazine in 1932 praised Gaza City's lively markets, its antiquities, such as the ancient mosque, and its good communications, since it lay on the rail link from Haifa to the Suez Canal.

- Juan Cole

The pledge of the Balfour Declaration took on a significance beyond the relatively small Zionist movement in the 1920s and 1930s, with the rise of virulent European fascist movements that made Jew-hatred a centerpiece of their projects. Polish anti-Jewish measures and the antipathy to immigration in the United States caused Jews seeking to emigrate to go to British Mandate Palestine. The Jewish population there had swelled to about 175,000 by 1931. By 1939 it had nearly tripled to over 457,000. These Jewish immigrants were refugees from an unprecedented paroxysm of murderous European racism, not for the most part committed Zionists with a program for settler colonialism. Once in Palestine, and given the horrors of the 1940s, however, some of them became available for mobilization by the ideological Zionists. This enormous influx of displaced Europeans created conflicts with indigenous Palestinians.

Notables and townspeople in Gaza joined in the strikes and demonstrations of 1936-1939, the "Great Revolt," which protested British colonial rule and the policy of allowing in thousands of European Jews. The uprising was begun by Ezzeddin al-Qassam, whom the British killed late in 1935, making him a martyr. Militias proliferated among Palestinians and immigrant Jews. The British military allied with the Haganah, one of the local Jewish militias, in putting down the revolt. Nevertheless, in May 1939, the Colonial Office under Malcolm MacDonald put forward a White Paper that laid out a plan to halt Jewish immigration and to create a Palestinian state by 1949 that would contain a Jewish minority.

Instead, the British after World War II announced that they would abruptly depart Palestine. The Zionist militias took advantage of this looming power vacuum, undertaking attacks on British and Palestinian targets in hopes of reversing the MacDonald White Paper. The Mandate fell into civil war. A shockingly unbalanced and anti-Palestinian U.N. General Assembly advisory plan for partition issued in late 1947 made things worse. The partition plan raised the hopes of the ambitious Zionists that they could defy expectations that they would become a model minority in an independent Palestine and instead establish a state for themselves on a territory far greater than the 6 percent they had managed to purchase and settle.

As the civil war unfolded, the commanders on the ground were emboldened and began deliberately chasing out the Palestinian population. Historian Joel Beinin, reviewing the findings of Israeli historian Benny Morris, observed that in July of 1948, the Arab Affairs director of the leftist Zionist Mapam party, Aharon Cohen, received a copy of a report from military intelligence. It explained why 240,000 Palestinian Arabs had fled from the regions awarded to the Jews by the 1947 U.N. General Assembly partition proposal and another 150,000 left the Jerusalem region and territories suggested for the Arab state. As Beinin wrote: "Cohen was upset to read the report's conclusion that 70 percent of these Arabs had fled due to 'direct, hostile Jewish operations against Arab settlements' by Zionist militias, or the 'effect of our hostile operations on nearby (Arab) settlements.'" The left-wing Mapam politicians had not aimed for this ethnic cleansing, but politicians by then were not in control of events on the ground.

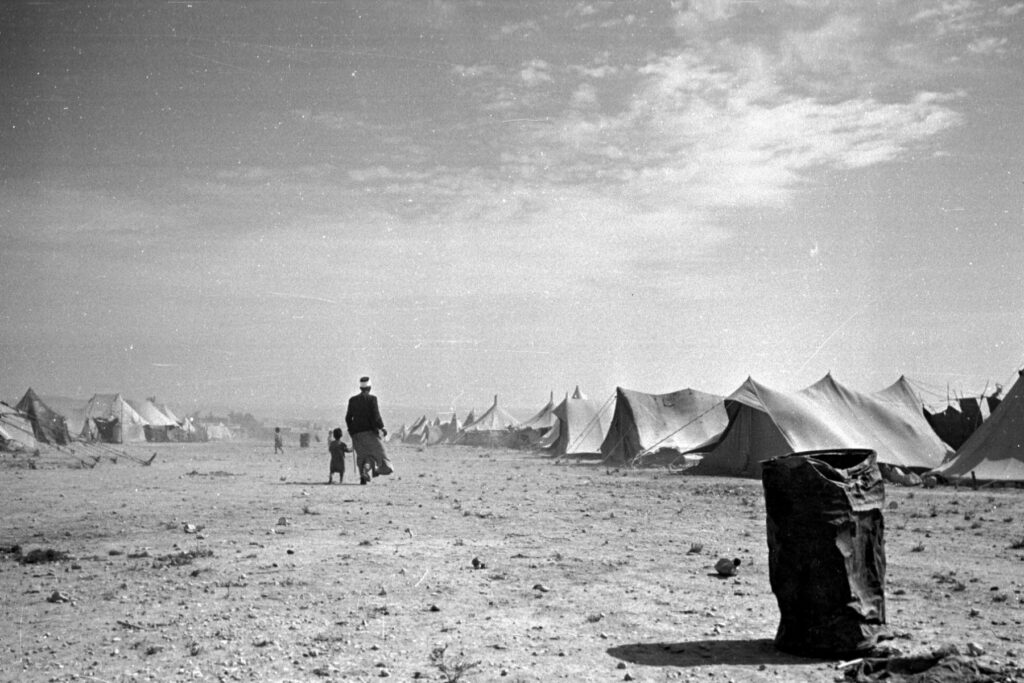

Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon, with a little help from Iraq, came into the war, though often with relatively small forces. The sheer number of troops on each side was roughly equal. The green Arab troops, however, were no match for the well-organized Zionist forces, some of whom had served in the anti-Nazi resistance or in the British Army, and who obtained good weaponry from Czechoslovakia. Jordan seemed mainly interested in grabbing the West Bank for itself and did not otherwise pose much of a challenge to the Zionists. The bureaucrats of the corrupt Egyptian government sold off equipment on the black market that should have gone to soldiers at the front. By the time of the 1949 Armistice, some 750,000 Palestinians had been ousted from what became Israel. In the south, around 250,000 of them were expelled to Gaza, where they swamped the 80,000 locals, becoming 70 percent of the population in what now was referred to as the Gaza "Strip," five miles wide and 28 miles long. They never received any compensation for the property they lost or for having been made permanent refugees

By the time of the 1949 Armistice, some 750,000 Palestinians had been ousted from what became Israel. In the south, around 250,000 of them were expelled to Gaza. They never received any compensation for the property they lost or for having been made permanent refugees.

- Juan Cole

Egypt served as the caretaker for the Palestinians of Gaza for the succeeding decades. The Strip suffered from being cut off from its agricultural hinterland, which was usurped by the Israelis, and from its traditional trading markets in what became Israel and the West Bank, a separation that contained the origins of its long-term food insecurity. Egypt co-administered the territory, the population of which had been rendered stateless, with the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees.

During the 1967 Six Day War, which Israel's leadership launched in hopes of humiliating Egypt and vastly expanding its territory, Tel Aviv's armies captured Gaza, the West Bank, the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. By the 1970s, powerful elements of the Zionist establishment in Israel had decided to attempt to colonize the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT). In Gaza, Israeli economic policies, including restrictions on water use, began a process of "de-development."

While Egypt recovered the Sinai Peninsula with the 1979 Camp David Accords, the latter functioned as a separate peace. With the largest, best-armed and most capable Arab army out of the game, Israel could do as it pleased with the Palestinians in the OPT, and its hard-liners pleased to colonize them and annex their land. Some Israeli governments at some points, as with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1993 or Prime Minister Ehud Barak in 1999-2000, showed a willingness to compromise and to seriously consider a Palestinian state (though a very weak one that Israel could be sure to dominate). Their wiser instincts were overruled, however, by the rising Israeli right wing, embodied at first in the Likud Party.

The rise in political power of conservative Jews from the Middle East (mizrahim), many of whose families had been expelled by mobs after the dispossession of the Palestinians in 1948, shifted the country to the right. So too did the arrival in the 1990s of 1 million Russian and other immigrant Jews from the old East Bloc, many of whom were hungry for living space and resources and opposed relinquishing the West Bank and Gaza.

Inside Gaza under Israeli occupation, a hothouse atmosphere of resistance grew up. Large numbers of people gave their loyalty to the umbrella group of secular and leftist parties, the Palestine Liberation Organization, which had many grassroots organizers and which sponsored institutions such as Gaza's al-Azhar University (a secular school not related to the Egyptian seminary). The PLO, led by the Fatah party, recognized Israel in 1993. Palestinians in Gaza were and are religiously and politically diverse.

Hamas's narrow victory in the 2006 elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council has created an image of fundamentalism as more hegemonic in Gaza than it is, in part because of winner-take-all electoral rules that led to disproportionate outcomes. Aaron N. Bondar observed of the 2006 elections: "There were 170,021 votes for Hamas (Change and Reform) candidates in North Gaza and 146,818 votes for Fatah candidate; a total of 390,194 votes were cast. Hamas, despite receiving only 44 percent of the vote, gained 100 percent of the seats."

The Muslim Brotherhood, a fundamentalist organization dedicated to political Islam and founded in Egypt in 1928, had established a small branch in Gaza in 1936. It was a decidedly minority taste for most Palestinians. Palestinian politics has often had a secular, nationalist or leftist overtone. Practicing Muslims among Palestinians were usually moderate traditionalists rather than fundamentalists, and mystical Sufi orders remain active in Gaza. The Brotherhood gradually built a following, however, by constructing a network of mosques, clinics, soup kitchens in desperately poor Gaza, supplementing the work of UNRWA and other aid organizations.

A group drawn from the Brotherhood formed the core of the radical Hamas organization, founded in 1987. In response to Israeli strikes on Gaza and Tel Aviv's strangling of its economy, the Hamas paramilitary, known as the Ezzeddin al-Qassam Brigades (after the Palestinian resistance leader killed by the British in 1935), began conducting reprisal attacks on Israel in the 1990s. The non-state militia was straightforwardly committed to violence as a form of resistance, and it made no distinction between military and civilian targets. Hamas played a part in torpedoing the 1993 Oslo Accords, which it viewed as fatal to its maximalist (and wholly unrealistic) demands for an overthrow of Israel, with a series of high-profile attacks on civilians. In response to provocations and attacks by the government of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, including the de-development of the Gaza economy, it engaged in another round of terrorist operations from 2000, killing hundreds of Israelis, though Israelis killed far more Palestinians with air strikes.

Hamas was, however, capable of concluding and honoring a truce with the Israelis for a year or more at a time (sometimes it was the Israelis who violated such understandings). The extended family unit of the Palestinians is the Hamulah or clan, and Hamulahs make up a republic of cousins bound by loyalty, honor and feuding with other clans. The impoverishment of these clans made it easier for Hamas to penetrate and tame them. It has been argued that Hamas subdued the Hamulahs in part through violence and in part through mobilizing them into an informal judicial system for settling conflicts. Where even one member of a Hamulah joined Hamas and was subsequently killed by the Israelis, that person's male relatives—brothers, uncles and cousins—would feel a responsibility to declare a blood feud and take revenge on Israel.

Successive Israeli governments also used Hamas for their own purposes, to keep the Palestinians politically divided and to weaken the PLO, and to represent themselves as defending the Israeli public from (largely ineffectual) Hamas rockets. The Israeli economic boycott devastated the small Palestinian middle class in Gaza, the only force that potentially had the resources to resist Hamas, and some proportion of which favored the secular-minded PLO.

*

Editor's note: This essay is adapted from Juan Cole's new book, Gaza Yet Stands.