Ex-US officials say, "Israel's campaign in Gaza and US support for it has been disastrous by every measure"

Nine former U.S. government officials who resigned in protest of U.S. policies during the Gaza conflict discussed the failures of the Biden administration's policy towards Israel during the Gaza conflict in a July 17, 2024, online event hosted by DAWN.

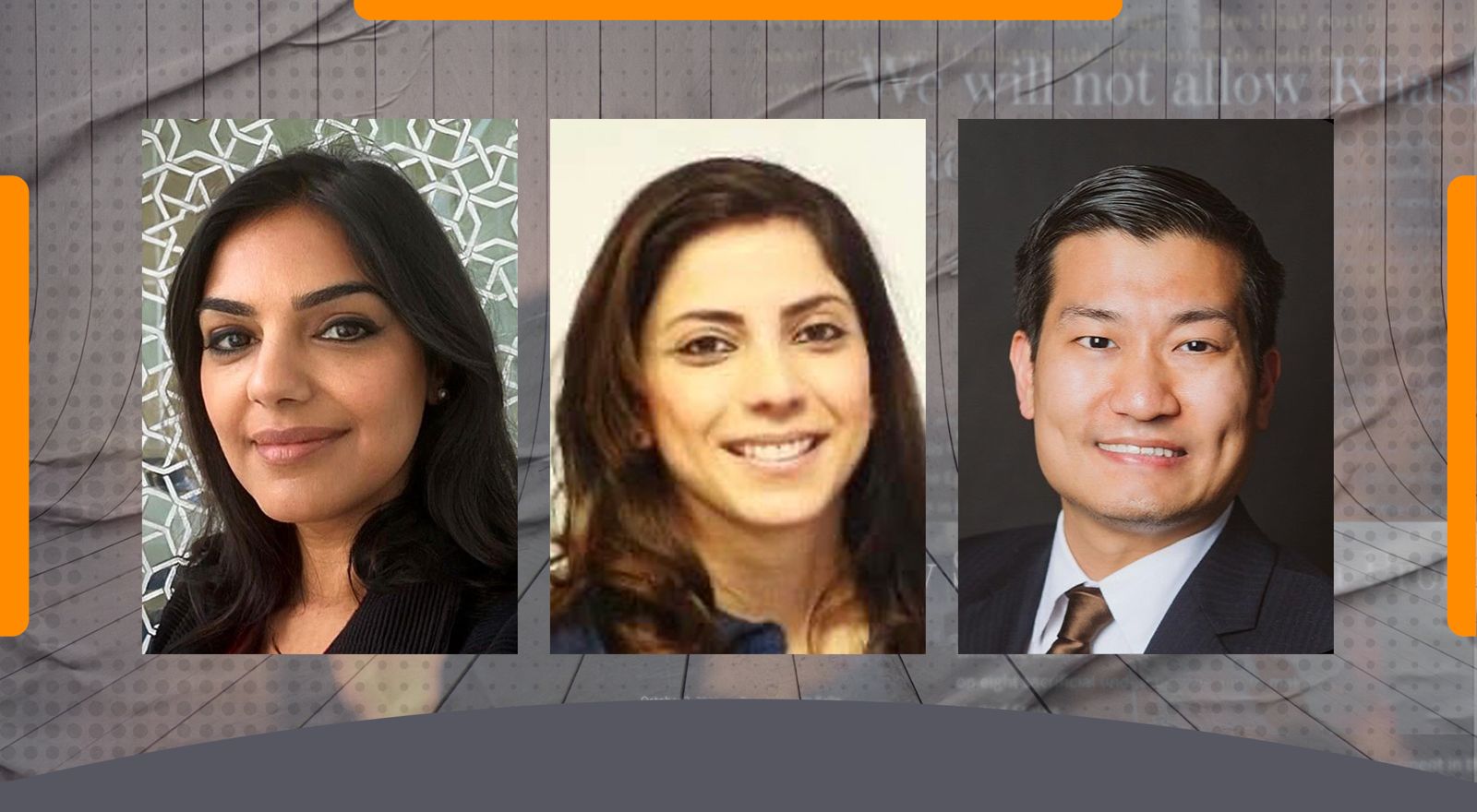

The distinguished panel included:

- Mohammed Abu Hashem (Resigned: Air Force)

- Stacy Gilbert (Resigned: Department of State)

- Lily Greenberg Call (Resigned: Department of Interior)

- Tariq Habash (Resigned: Department of Education)

- Maryam Hassanein (Resigned: Department of Interior)

- Harrison Mann (Resigned: Defense Intelligence Agency)

- Josh Paul (Resigned: Department of State)

- Annelle Sheline (Resigned: Department of State)

- Alex Smith (Resigned: US Agency for International Development)

Sarah Leah Whitson, the Executive Director of DAWN moderated the event.

The panelists explained their recent Joint Statement: "Service in Dissent," the reasons behind their resignations, and answered questions from the audience on issues ranging from foreign policy, to U.S. politics, to the question of what those still in government should do in an immensely difficult situation.

The full video of the event is viewable below. A transcript of the first half of the event immediately follows the video. The transcript of the remainder of the event will be posted here when completed.

Event Transcript

Voices of Conscience: Former Government Officials Discuss Failures of US Policy in Gaza War

Sarah Leah Whitson: Hi everyone, welcome to the Voices of Conscience gathering of former government officials here to discuss the failures of US policy in the Gaza war. We are joined here by eight, and I believe now nine, former government officials who are going to join us in this discussion as we review a number of questions, including a policy statement that these former officials have put together. I think this is an incredibly important event that DAWN is organizing and it is taking place as we discover government officials who felt they were no longer able to influence the conduct and policies of the United States during the past nine months of this heinous war in Gaza.

By way of introductions, my name is Sarah Lee Whitson, and I am the Executive Director of DAWN. DAWN is an organization whose central mission is to reform US foreign policy in the Middle East and to end US support for abusive regimes in the region that are not only terrorizing the people in the region but also undermining US interests, standing, and credibility globally.

We are joined today by a number of former government officials who I am going to briefly introduce by name alone before we delve into specific questions that we're going to address to all the resigness today and I am going to be briefly noting their names without any details of their bios until we actually proceed to the event. But we are joined today by Josh Paul, who is now a special advisor at DAWN; Hala Rharrit; Annelle Sheline, who is back at the Quincy Institute; Alex Smith; Major Harrison Mann; Major Riley Livermore; Maryam Hassanein; Tariq Habash; Sergeant Muhammad Abu Hashem; Lily Greenberg; Ana del Castillo; and Stacy Gilbert, who is now able to join us. We are so glad she was able to join us.

Let me start out, first of all, by thanking each of you for your courage and for your principled positions, and the great personal costs that you have undertaken to stand for your principles. But also, in particular, to thank each of you for your continued engagement and your continued service to the United States and to the interests of the United States, and for continuing to use your voice and your platform to help reshape America's disastrous policy in the Middle East.

I want to start by asking Josh Paul to lead this discussion. Josh, as you know, resigned from the State Department in October. He had previously served for over 11 years as Director in the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, playing a senior role in US defense diplomacy, security assistance, and arms transfers.

Josh, I want to kick this event off by asking you to contextualize the joint statement that you and your colleagues put together and kick off this discussion here for us. Just before we do that, I will let the audience know, and thank you all for joining us today, that we will be opening up for questions and answers at the conclusion of the comments that the presenters will be making, which should last about just over 30 minutes. With that, I will turn it over to Josh.

Josh Paul: It really is a great honor to be here alongside co-panelists and co-signatories of the joint statement that we put out shortly before July 4th, called "Service in Descent." What we will do is just briefly walk all of you through the joint statement that we did and add a couple of other observations and then, as Sarah Leah says, open it up for questions.

I just wanted to open up by talking about why we are doing this, and I think it's pretty unique. There have certainly been resignations over other US foreign policy matters: over Iraq, over US policy towards Syria, the Balkans at various points. But to our knowledge, and I've heard this from a couple of historians, this is the first time that resignees over an issue have come together to issue a joint statement. So why did we do this? And why are we all here as a group in front of you today?

You may have heard of the parable of the elephant. There are a group of people, blindfolded, who are touching different pieces of an elephant and one feels the trunk of the elephant and says, it's a snake, one feels the leg of the elephant and says it's a sofa. The answer is that each of us, and what you have here, is a cross section of the interagency, from the State Department, from the Department of Interior, from the US military, from the White House, from the Department of Education: civil servants, foreign servants, military officers, and political appointees. Each of us, in the course of the last year, touching a different part of the problem, that is the administration's policy towards Gaza and towards Israel-Palestine.

And so, first of all, we felt like we all had a piece of that puzzle, and it was important for the American people that we bring that puzzle together and demonstrate the collective understanding that we have built of what is going wrong and what needs to be done to fix it. The second reason, of course, is that speaking together, we are stronger and louder, perhaps, than any of us can be individually. We are each working in our own lanes and happy to talk about that. But by standing together, we hope that we can send out a stronger and clearer message, including to this administration. The third reason is support to our colleagues. We know that there are hundreds and actually thousands of people across government who are struggling on a daily basis with what they should do with the moral quandary that they are in as a result of their role, whether it is direct or indirect, in policy in this area.

And again, as a group, we wanted to be able to reach out to them with our support and our thoughts, and so we want to address that. And the final thing, we released the statement on July 2nd and this is ultimately about America's interests. We may no longer be working in the US government, but we still care deeply about what America does around the world and how that impacts all of us here at home. We wanted to make the point that we may be leaving, we may have left the government, we may be speaking out, but that is very much a further step in accordance with the oath that we all swore and that dissent, when a government is making decisions that are taking our country and its foreign policy off the rails, is ultimately patriotic. So we will now briefly walk through each of those elements of the joint statement, add a couple of further points, and then be open to your questions. So let me hand it back to Sarah to introduce our next speaker.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thanks for that, Josh. I will now just briefly introduce Harrison Mann. Good to see you in person, at least via video, Harrison. Harrison is a former US Army Major and executive officer of the Defense Intelligence Agency for the Middle East and Africa. He resigned in protest of his office's support for Israel in the ongoing war in Gaza and previously served as a Middle East intelligence analyst and led a crisis cell coordinating intelligence support for Ukraine.

Harrison, can you walk us through the current crisis? The sort of facts on the ground that led to your own decision to resign from the government?

Harrison Mann: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, my assessment was, and our assessment together is, that Israel's campaign in Gaza and US support for it has been disastrous by every measure. We have tens of thousands of Palestinian civilians who have been killed directly by Israeli operations. And on top of that, because Israel has destroyed most infrastructure in the Gaza Strip and largely cut off and restricted aid, we have multiples of those who are dying, or on track to die, from starvation, lack of medical care, lack of water, and lack of shelter.

This is exacerbated by the US cutting aid to UNRWA, which is one means that could have provided some level of relief to the suffering of the Palestinians right now. And all this—everything we see in Gaza—would not be possible without US support at the level that we've maintained it for the past nine months. Not just cutting off UNRWA, not just diplomatic support for Israel, but we have US troops who are engaged in combat right now in the Red Sea, defending Israel from external attacks so they can continue to prosecute this campaign. Of course, the most important feature of our support has been providing munitions. The Israelis could not have continued in Gaza for this long, or at this scale, without an endless flow of weapons and ammunition from the US. I just want to emphasize that there is no substitute in the world who can provide this quantity at this speed except for us. So, without us, the war could not exist in its current form and intensity.

And we have very little to show for it. We are all—both Israel, the US, and everybody in the region—worse off than we were on October 8th. Hamas is still a threat, the hostages are not back, Israel has made itself a global pariah, and it has dragged the US down with it. I think the US has permanently lost the ability to use a values-based argument to rally global partners, unlike the way that we did quite successfully when Russia invaded Ukraine. We've turned both global and, especially, regional opinion against the United States in a way that we haven't seen, maybe, since the invasion of Iraq. That is breeding hatred that is undoubtedly going to cause terror in the future. I think it's only a matter of time until we reap what we sow there.

Finally, our unconditional support has not only prolonged the war in Gaza, but it's also helped fuel this regional escalation. We have, I think, six countries in total, or forces in six countries, that have become belligerent. The aspect that worries me most is the continued escalation between Hezbollah and Israel on the northern border. We are again empowering Israel to escalate more and more, and this could lead to a full-scale war: Israel invading Lebanon, bombing Beirut. That threatens to draw in the United States and put US forces, bases, embassies, and troops in the region at risk when we become a target because we look like we're a direct participant in that conflict. So, I'll just conclude by saying that not only are more people in the region, but more Americans are on track to die because of poor policy.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you for that, Harrison. Next, we'll turn to Annelle Sheline. Annelle is a friend of mine and a research fellow in the Middle East program at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. She previously served as a foreign affairs officer at the US State Department's Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor before resigning in March, also in protest over the Biden administration's policies with respect to Gaza.

Annelle, how did it go wrong? What did you observe during your time at the State Department that coincided with the start of this war in Gaza, and that led to your decision to resign from the State Department?

Annelle Sheline: So, you know, I want to make clear that the problems we're seeing now did not start in the aftermath of October 7. The vast scale of US support for Israel is something that should have been subject to vigorous debate for years. And yet, for years, any serious discussion of rethinking US policy has been actively suppressed or subject to self-censorship, both inside and outside the government. This was absolutely something I observed at State before October 7. And I can also speak to this as a former academic. I remember being told explicitly that even when teaching classes on the Middle East, it was really just best to not get into the question of Israel.

I think, in specifically thinking about the ways that the US government is sidestepping laws, these are especially alarming and were a big part of why I resigned. US law is clear; I'll mention a few laws. For example, the Leahy laws clearly state that the US cannot provide security assistance to units of a military engaged in gross violations of human rights. Similarly, Section 6.20.i of the Foreign Assistance Act states that a foreign government that is blocking US humanitarian aid is no longer eligible for security assistance. What we have observed instead, in the aftermath of October 7, is that the State Department has illegally bypassed Congress to rush money and weapons to Israel. I observed how lawyers inside the State Department assisted with efforts to avoid implementing US laws.

All of this is made possible within this broader context in which Palestinians are systematically dehumanized. We see this in the media and we see this very much coming from the administration. Their actions and statements have repeatedly made clear that the US government considers the lives of Israelis more valuable than those of Palestinians. But simultaneously, the administration is using the American Jewish community to justify its policies in ways that only reinforce the risks of anti-Semitism.

Over and over again, we've seen the administration emphasizing politics rather than facts. The Biden administration is not only actively facilitating genocide, but it is also doing irreparable harm to US national security. As Harrison mentioned, this is extremely dangerous for our troops in the region. This is also dangerous more broadly, in terms of American soft power and the US government's ability to work productively with other countries. While I was inside State, I observed how the pursuit of great power competition was very much a key objective. And yet, even this supposedly crucial goal is seen as less important than this unconditional support for Israel. Despite the direct effect of undermining the US standing beside China and Russia, the hypocrisy in calling out Russia's invasion of Ukraine while supporting Israel's actions in Gaza was particularly blinding. Having sat in the office focused on human rights in the Middle East, I don't know if there's any way for us to regain credibility as an advocate for the rule of law and for human rights.

Sarah Leah Whitson: That is an unfortunate assessment, and I think we'll get into that a little bit more in the question and answer. I want to turn now to Tariq Habash. Tariq was serving as a political appointee and policy advisor at the US Department of Education, working to address some of the domestic ills we face, like our broken student loan system. He was the second government official and the first political appointee to publicly resign from the Biden administration.

Tariq, what are your thoughts on what the Biden administration can be doing differently? What are your recommendations in the joint statement to the Biden administration?

Tariq Habash: Thank you so much. And thank you to DAWN for hosting this conversation with us. I think it's clear, just based on what Josh, Harrison, and Annelle have already talked about and their experiences, that there has been a complete disconnect between how US policy is dealing with Palestine, with Gaza, and how it responds to other crises around the world.

I think the first and foremost issue that we really need to be thinking about is consistent execution of the law. The reality is, to Annelle's point, that the US administration has, even prior to October 7th, gone to great lengths not to apply consistent application of US laws toward Israel. I'll raise two very specific laws: the Leahy Law, as well as the Foreign Assistance Act. These are really instrumental in ensuring that we make a real shift in American foreign policy in the region and in ensuring the humanization of Palestinians and ending the continued supplying of weapons in circumstances where international humanitarian law has been clearly violated, which has been resoundingly determined by human rights organizations around the world.

Second, increasing and expanding humanitarian assistance is a very obvious one. This is something that we've heard politicians here in the United States repeatedly talking about without real substantive solutions on how we do that. The reality is that, so long as there is an impediment to humanitarian aid reaching extremely vulnerable Palestinians living in Gaza, we're going to continue to see an increasing deterioration of the circumstances. I think just in the last week or two, we saw an analysis that came out stating that 100% of Palestinians living in Gaza have experienced some level of food insecurity and hunger, with the vast majority of them suffering from much more extreme circumstances of famine and starvation. This will have lasting effects for generations on Palestinians. Finding a way and pushing and prioritizing humanitarian assistance to Palestinians in Gaza must be a priority, as well as investing in the reconstruction of Gaza. The reality is that it's our weapons that are causing the destruction primarily. Therefore, we must be leaders in that reconstruction to ensure that it does not take generations to rebuild Gaza but that we do it as fast as possible to be able to support Palestinians.

As we think about long-term support for peace, we have to also consider supporting self-determination for Palestinians. The unfortunate reality is that, in both the past administration and this administration, Palestinians have largely been left out of conversations about normalization and peace in the region. In order to fully support peace, there must be a legitimate voice for Palestinians in that conversation, and there must be an end to the military occupation and the continued illegal settlements that violate international law as well as violate US stated policy in the region.

Lastly, I think it's extremely important to immediately and permanently end the existing conflict and achieve the release of all hostages, both Palestinian and Israeli. There are thousands of Palestinians being held in administrative detention without cause, and it is important, in the context of releasing Israeli hostages, that we also recognize that Palestinian civilians have been subjected to horrific conditions, torture, and starvation. This must end in order to achieve real, lasting peace.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you for that, Tariq. Next, we turn to Lily Greenberg Call. Lily is a former Special Assistant to the Chief of Staff of the Department of the Interior, with nearly a decade of experience in politics, organizing, and domestic and international human rights work. In fact, she also worked on President Biden's 2020 campaign. Lily was the first Jewish political appointee to resign in protest of US policy in Gaza.

Lily, what is your message? What is the message of this group to your former colleagues who are still serving the administration as it pursues its policies in Gaza?

Lily Greenberg Call: I mean, I think our overarching message is that the majority is with us. I spent the first eight months since October 7th, while I was still in government, organizing our colleagues across government around dissent about this. It was very clear to me that while our leadership may be out of touch and refusing to listen to not just the majority of the American people but the majority of their staff, there is widespread dissent within the administration, across all agencies and ranks, seniority.

So, I want people to know that they are the majority, that they are not alone, and that there are undoubtedly colleagues of theirs who maybe share their distress and frustration, and their feelings of desperation. We want people to remember that they have power. We know it can feel very difficult to speak up; we know there are insurmountable obstacles, systemic obstacles, and financial obstacles that people face if they are deciding whether to leave their jobs or not. But if you are staying, you still have quite a bit of power. And the worst thing is for people to forget that they do have that.

So, question policies that you think are unjust or illegal. Challenge those decisions. Organize among your colleagues. Don't be afraid to bring this up. I know that within my agency, we didn't necessarily work on this issue; we don't work in foreign policy. There was a huge culture of silence and a fear of bringing this up because it wasn't, to quote, "relevant to our work." We really want to encourage you all to push through that fear you might be feeling, to talk to your colleagues about this, and to use the power you have to challenge things that you think are unjust, unfair, or maybe even illegal. Use the tools at your disposal, use protected channels, talk to your inspector generals, talk to legal advisors. Really question things, and don't let the hierarchy or the culture of silence around this, or even the notion that some people know better than others, deter you. If you know that something is wrong, you know it's wrong. You don't need someone to tell you that it is or isn't, and there are avenues for you to challenge what's happening within the system.

Also, know that there's support from the outside. You have all of us here to support you and advocate for you. You have organizations, you have a whole collective of people who are rooting for you on the inside to use the power and proximity that you have to continue making a difference.

So, I think that's one thing that, when I was even thinking about resigning—and I know the sentiment is shared among the resignees—was thinking about what was on the other side of this. It was very scary because so much of what we knew was working in government and our colleagues and our communities in there.

I hope that people take away from this that that community and those colleagues are probably more aligned with you than you might think. And even if you feel like you're taking a risk, there are people on the outside to catch you and support you, whether or not you stay on the inside. But you still have a lot of power. The worst thing is for people to forget that there are tools at their disposal to challenge what's happening.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you for that, Lily. And I suspect we're going to have quite a number of follow-up questions for you on this topic.

I want to move now to Senior Master Sergeant Mohammed Hashem. You've served in the Air Force for 22 years, advising commanders on morale, welfare, and providing military units with a ready mission force. And yet, you have resigned from the Air Force. I wonder, what are you hearing from former colleagues in the US military since your resignation?

Mohammed Abu Hashem: In my former role, it was my responsibility to provide a mission-ready force for unit commanders. This includes the welfare and morale of each troop, ensuring they are taken care of. It also means looking ahead at issues to avoid disrupting mission readiness.

Speaking with former colleagues, there's been a lot of dissent regarding the handling of this conflict. This has led some members from various service branches to file for either conscientious objector status or miscellaneous separation reasons. Obviously, both types of separation take time to process.

Additionally, some of my former colleagues have seen a larger number of members seeking medical assistance for anxiety. This is largely due to the U.S. continuing to state that it will support Israel if it goes to war with Hezbollah or Lebanon. Other reasons for seeking medical assistance include the exacerbation of previous traumatic experiences, which, in some cases, lead to PTSD. These conditions may be due to each member's personal morals or ethics or due to past trauma exacerbated by seeing everything unfold live on their social media platforms. This is not easy for them.

The current situations our military affairs are facing culminate in the disruption of military readiness. We've seen in the past that a significant number of service members become ineligible to deploy until they receive this type of care. This adds to the stress of members who have returned from tours overseas and face the prospect of additional deployments, leading to their own personal and family stressors.

I know we want to believe that military members are much more resilient, but underneath each uniform is a human being with the same common life stressors as anyone else. We've seen the lasting impacts of Iraq and Afghanistan on our servicemembers. According to RAND, about 20% of members who returned from either direct or indirect involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan have reported signs of PTSD. That's over 300,000 military personnel at a cost of $12 to $14 billion per year post-military service. The key word here is "reported." It's unknown how many members have not reported yet.

I've personally seen members, and I've talked with members, who took 18 or more years to report any signs of trauma related to those conflicts. Now, with the genocide unfolding live on their phones, they feel that it's morally wrong but cannot break out of the contract they signed into.

This, to me, plays a huge role in affecting those service members and their readiness. Lastly, this also impacts our colleagues who, for 10 months, waited for the administration to change course on its unconditional support, while U.S. and international law were being blatantly violated. This affects military readiness because once you cross an individual's moral red lines, it renders them ineffective at work.

I continuously receive messages from members still serving who say they're having a difficult time showing up to work or even performing their basic tasks. Even more concerning, a small number have utilized legally obtained substances as a means of coping because it renders them incompatible with military service.

I know this has affected me as well. Since I decided to step away, I was unable to do my job effectively as of October 21. Unfortunately, it took until June 1 for me to be completely separated from the service. When you consider how this has affected everyone's lives and daily tasks, it has a significant, though largely unknown, impact on our national security.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you for that, Hashem. The information you've shared is indeed distressing, and I anticipate there will be follow-up questions.

Now, I want to turn to Maryam Hassanein, a former political appointee in the Biden Administration at the Department of Interior, who also resigned in July due to the administration's policy on Gaza. Maryam, can you share what you are hearing from former colleagues in government regarding this issue?

Maryam Hassanein: As the most recent resignee, I have a recent gauge on the conversations within the administration. To echo Annelle's point, one of the main issues is this pervasive culture of silence during a time of significant crisis—specifically, the genocide that's occurring.

At least within my agency, there was an expectation that the crisis, driven by Israeli actions and US funding and enabling, was not to be explicitly discussed. This topic has not been openly addressed for a long time, despite staff wanting and needing such discussions. Although there were listening sessions held last year, many attendees felt that their input was not fully considered or heard. For an administration that prides itself on diversity, it needs to do much more to listen to diverse voices in a meaningful way.

And I would also add, to Lily's point, that there's a significant amount of dissent within the administration. It's not just the twelve of us who have resigned from the executive branch—many others have left, and there are still people inside trying to organize through actions like sickouts, vigils, and other events. This ongoing dissent reflects that both within and outside the government, there is still significant opposition.

Lastly, with Biden appointees in particular, who are there to support the administration's agenda, there's a conversation being had about how the administration's denial of genocide and its stance on crossing red lines not only undermines its credibility but also harms the President's reelection chances. This issue should be taken seriously, as it impacts not just the administration's political future but also domestic concerns. If the administration and its leaders want to advance on other fronts domestically, it's crucial that they heed the majority of Democratic voters who are calling for a ceasefire, an arms embargo, and a more effective approach to alleviating the crisis we are witnessing.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you for that, Maryam. And thank you for that disturbing analysis.

Let me turn now, to Alex Smith, a lawyer with a background in global health development, human rights and international criminal law. And in May 2024, Alex was working at USAID, but left after four years of service due to the agency's own policies, statements and silencing of speech about health conditions and war crimes in Gaza. So clearly, this is not just a problem of the State Department or the White House. But here, we have a dissent from within USAID itself. Alex, can you comment on that a little bit, but also tell us what's next for this very important joint effort of this group of really conscientious objectors who have resigned from the government?

Alex Smith: Sure thing. Yeah, so I wanted to follow on to what Annelle and Harrison and many others have been saying about, obviously, these are violations of domestic law. And they do make the US less safe, they make personnel less safe to make aid workers less safe. People like me who are working in other countries.

But on top of that, as you said, my background has been in international law. I was very happy to have done a fellowship at the International Criminal Court in The Hague, working for the prosecutor's office on cases from DRC and elsewhere around the world.

So from my perspective, from the international law perspective, it's shocking and really distressing to see the US making the decision now to basically burn down the framework of international human rights that has been built after World War Two. The US has never been a very active participant or not, not since the 40s have we been a very active participant in that system. But we didn't actively try to destroy that system or block that system. We didn't try to formally say these people are people and these people are not people, until now. And it's, as others have said, the contrast between this conflict and Ukraine is startling. If you go to USAID's website today, you can find a very peppy video about our commitment to helping the people in Ukraine. It's called One Year Later Helping Ukraine with War, Build a Lasting Peace.

Not only are we providing health services, and I volunteered for those early initiatives to try to rebuild Ukraine's health systems. We're also engaged in human rights work there, working to document Russian crimes. And as everybody saw, we can have two weeks ago, there was a hospital bombed in Ukraine. And there was great outrage among US lawmakers, but not for the 36 hospitals bombed in Gaza. So those, you know, as seeing this from an international perspective, it's really shocking, and really frustrating to see some people being defined as not quite people.

To your question about what's next, we do have more initiatives coming up. We're always talking about having joint statements to condemn specific policies. But we're also going to be involved in helping other colleagues come out and speak against policies from within agencies. We're also going to be loudly advocating for human rights and fairness in US policies. And we're going to be speaking out for people in government. We're always happy to help people who are in the pipeline of deciding to resign, or to stay and do the best they can in the systems that they're in.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you for that, Alex. I want to now turn to Stacy Gilbert. Stacy, thank you for joining us today. Stacy was the senior civil military adviser for the Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration at the State Department where she worked for over 20 years. Stacy, you also resigned from the State Department because of our policies in Gaza. And the question I have for you and perhaps to others, but in particular to you, what was what was the red line? What was it that made you say, Okay, this I can no longer be a part of or represent.

Stacy Gilbert: Thanks for hosting this conversation. For me the red line was very specific. I was working on a report that was required, according to the National Security Memo 20, NSM-20. And it was a joint report to Congress from the State Department and DoD. And we were to look at two things for a variety of countries. But the country that we were most interested in was Israel. And it was to make a determination on two things. One is whether Israel was using US weapons to violate international humanitarian law or IHL. And two, whether Israel was blocking humanitarian assistance. So the report came out on May 10th. I was surprised when I read the report, it said, it was actually the first time I'm aware of that we admitted that the US has determined that Israel was likely using US weapons to violate international humanitarian law.

But I was shocked to see it say in very stark terms that we determined that Israel is not blocking humanitarian assistance. That was not the consensus of humanitarian subject matter experts in the US government, nor around the world. So to see that written in a joint report to Congress, a fact that was so obviously demonstrably false, was shocking to me. And when that report came out on May 10, that's when I let it be known that I would resign.

To me the red line is, you know, we can have discussions about policy. We have, you know, different opinions about policy directions. But when you dismiss, deny or obfuscate facts, that is something different. That is, I thought this administration was not going to use alternate facts, and the fact that we stated so clearly, in a joint report to Congress that we think Israel is not blocking humanitarian assistance when that is clearly what they have been doing in all different ways, since this conflict began. You can't have a famine in an area without there being some kind of deliberate blockage of humanitarian assistance. And even when the State Department spokesperson says, you know, lists the various ways that the President of the United States, the Secretary of State, have implored Israel to let assistance through, is in fact, in admission that Israel is blocking humanitarian assistance. It's clearly not the only problem. Hamas plays a role in that. It's a conflict, it's difficult. But these organizations work in those kind of difficult and austere circumstances. They have the experience and the local knowledge to do those negotiations. But they are not allowed to, because Israel has blocked them.

So, my own thought was when that report came out, I was in a unique position, having worked on that report, to come out and say, that is not true, everyone knows it's not true. But the only way my voice would really be heard on that is if I left my position in the State Department doing work that I loved, with an office and a bureau and colleagues that I admire and respect. But I was better placed to leave the government and come out and call them on that denial of facts.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Alex, I want to ask the same question to you. What was your red line? You were in an aid agency, which is sort of tangential to the policy decisions. And yet clearly, there was a red line that was crossed for you. What was it?

Alex Smith: For me, it was also a very specific moment like Stacy's. I had in May, well actually back in February, prepared a lecture to give that was not a political lecture. It was about stating basic facts about maternal and child health in Gaza. It was not meant to, you know, make any political statements. It wasn't to throw bombs or anything. It was just to state facts. To say that starvation has these effects on people in conflict. That when you starve a population, when you starve pregnant women, you're going to see more infection. You're going to see more maternal mortality. You're going to see women who don't have enough iron, dying from bleeding during childbirth. So just stating the health consequences of this conflict and of conflict in general. But that presentation was very suddenly revoked from the conference agenda, was canceled at the very last minute.

So it was very distressing to see that speech silenced. Especially when we are very vocal, as I said before, about, about crimes in Ukraine and about conditions in other countries. So for me that was really where it came to a head. Because to me, human rights are universal. The right to maternal health is also enshrined in international agreements. So that was distressing to see this.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you. I'm just shifting our focus here a little bit. We have seen unprecedented protests in the United States, unprecedented outcries in social media, university campuses, newspaper editorials, reflecting significant shifts in public opinion on Palestinian rights and many polls back that up. The question really is, as political insiders, what your view is as to why the Biden administration and Congress have been so deaf to this change? And does the shift in public opinion with regards to US support for Israel mean there may be a shift in US policies? Annelle, I want to pose that question to you.

Annelle Sheline: Thank you. So, in terms of the intransigence, you know, Biden has been in politics for more than half a century. And during that time, he has never once observed a politician face political consequences for being too supportive of Israel. And we just collectively witnessed a politician, Jamaal Bowman, lose his congressional seat for criticizing Israel. He was taken down with millions of dollars from the Israel lobby. So although there is a generational change coming, as we've observed on college campuses, and in polls, it is not coming fast enough. And unfortunately, I think even if Bowman had won, or if it seemed more clear that it was no longer the smart political decision to support Israel, I think Biden's obstinance has also become clearer to the world. He refuses to take in new information or update his thinking, whether it's on support for Israel, or who would be the strongest candidate on the Democratic ticket, unfortunately.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Right. Well, on that note, Harrison, literally, what do you think the prospects are for US policy with respect to Israel? If there's a new Trump administration? Do you think things will be better or worse?

Harrison Mann: I'll jump in. And I'll start off with what I think is going to be the same. And I think really, in terms of what Gaza experiences, that's not going to change much. The Biden administration has already given Israel a carte blanche to basically do what it wants in Gaza. So you can't really get worse than that. I'm sure we'd see less conciliatory rhetoric from the Trump administration. But in terms of the experience on the ground, it's hard to imagine it being much worse than it is today. I mean, we've let them be unrestrained, and we've continued to support them, no matter what.

I think the probably worrying difference is that a Trump administration will be staffed with a lot more Iran hawks. So even though I think the suffering of the Palestinians is not going to be much better or worse.

The Biden administration has, to a certain extent, attempted to minimize regional escalation. They haven't been that successful, but they've been trying. If you are, you know, possibly J.D. Vance, or any other number of people who would like to see a war with Iran, you couldn't really ask for a better set of pretenses than you have. You know, Iranian-backed groups attacking us in the Red Sea, that's the Houthis, or Iranian-backed Hezbollah attacking Israel from Lebanon, and that's happening every day. So that is the biggest concern I have about how their policy could potentially be worse. And I do just want to add the caveat that though the current administration has kind of made a good faith effort to reduce escalation, they're still not willing to do the one thing that would ensure that we don't see this disastrous Hezbollah-Israel war, and that would be leveraging aid to force a ceasefire. I think Lily might have more about how things would be a little bit different as well.

Lily Greenberg Call: So yeah, I mean, I certainly think we can all agree that a Trump administration would definitely, you know, create worse conditions for us domestically, for stability, I think I'm under no illusions, and I don't think anyone is here, that it would be worse than that. I mean, particularly around our ability to organize on this issue in particular. I think the conditions for us, not that they are good here right now, we've seen this crackdown on student protesters and on freedom of speech, you know, and the anti-BDS legislation and the efforts to sort of codify anti-Zionism in the definition of anti-Semitism.

However, that being said, I do believe things would be much worse under a Trump administration. And that, you know, part of voting, as the great Angela Davis has said, is about voting for the conditions under which we can organize for a better future. And I do think we are in a better position to do that under a Democratic administration.

I also think the unfortunate thing to think about, that I have thought quite a bit about, is that if this was happening under a Trump administration, if the genocide was happening under a Trump admin, that there may be more pushback from the Democratic establishment and a more unified Democratic caucus, you know, both within the political establishment and political leaders and across voters and other people. I mean, I personally think that there may even have been a slightly different reaction from the establishment Jewish community if it was Trump sort of doing what Biden has been doing and justifying the war and also really using the language of Jewish safety to justify it. Because we are so clear that Trump is a, you know, is a white supremacist and is backed and supported by white nationalists. And that has been less, that is less explicit with Biden.

I do think, you know, on this sort of optimistic side, we may be at an opportunity now for a policy shift, if there's a change in nominee. I think we're, you know, no matter who the nominee is, they need to listen to the majority of their voters, the majority of the Democratic base, and the majority of the American people who want a ceasefire, and who do, I think, at this point, want a meaningful change to the status quo in Israel and Palestine.

And that our, if we are so lucky to find ourselves in a moment of real, you know, have a real opportunity for policy change on this, then we, as folks who care about this issue, need to be ready to present to a maybe more willing administration or Democratic leadership what they should be doing. You know, the problem is that the right is very clear and very in line, and, you know, maybe not very compelling to us, but it's very obvious what they want. And they're not afraid to ask for it. And I think, you know, on the left, sometimes we get a little too caught up in what is politically possible or, you know, what we think we can or can't do. And I think we need to be willing to be just as brave and just as brash as our opponents.

Sarah Leah Whitson: As we've been discussing, sort of parallel with the shift in public opinion, there's been vocal criticism, and vocal criticism of Israel. We have an unprecedented crackdown on free speech and attacks on civil society organizations, a number of whom are now facing lawsuits because of their criticism of Israel here in the United States. It seems that our government and powerful business interests are willing to sacrifice American freedoms, American rights, in order to protect Israel from criticism.

Do you think they're going to succeed in these efforts? And how do you think we can counter them?

Maryam Hassanein: I think we have to call it out for what it is until and to always counter narratives meant to delegitimize the movement. As we have seen, rhetoric from the administration is really powerful, and can embolden just negative false ideas. And that's something we constantly have to counter. I can speak to the younger generation, and also as someone who was inspired very greatly by the student movement and very observant of it. I just don't see that the younger generation that is already and will continue to be decision-makers and people to really listen to, I don't see them stopping being critical of Israel, while they're carrying out these actions. And I think the public opinion has changed really greatly. And from what I've heard from movement leaders, this is the most public support for Palestine they've seen in their lifetimes. So I don't see regression. I don't think that there's success there. But it's also important as a collective to recognize attempts by the administration and government leaders to delegitimize very real concerns and criticisms of Israel. And one way to counter that is to, like I said, call it out for what it is, and also meet people where they're at and continue to spread awareness. I think that nine months in there is an idea that surely everyone must be on the same page. But unfortunately, that's just not true. I think there is an obligation to continue educating people, to continue raising awareness. And I think that's one good counter strategy.

Lily Greenberg Call: I think we know what I can really speak to, here is this idea, and this narrative shift that I think really needs to happen about why there's support for Israel in the first place within the United States. And I think what people tend to think, and what is held up as the reasoning is one that Israel is a liberal democracy and aligns with US interests in that way. And then also this narrative that this is necessary for Jewish safety. And that is the reason why the US is such a strong supporter of Israel. I think the reality, of course, is that Israel isn't a liberal state. It is not a liberal democracy by any stretch of the imagination. And also that reality that the status quo is not only clearly devastating for Palestinians, but does not actually keep Israelis safe, or make Jewish people safe at all.

And I think a huge part of, if that curtain can be kind of, can uncover some of the real reasons why there is such a stronghold for continued financial and military support for Israel, within Israeli politics, I think that will do a huge part in making it more politically poisonous for folks in power to take money from groups like AIPAC than to not, you know, than to be

in support of a meaningful change, and support of Palestinian freedom, and self-determination. And I think, our role, especially as people on the left, is to work to deepen our analysis, in particular of antisemitism, so that we can effectively counter some of these accusations of antisemitism that will happen, and also to expose groups like AIPAC groups, lgroup ike CUFI. Even in a lot of ways I feel, you know, the the Biden administration itself, as organizations and people that are not invested in Jewish safety. Again, it's very clear, or it's more clear to some people with someone like Trump, with Republicans who may be very pro-Israel, and who are then explicitly antisemitic. And it is a little less clear when it comes to Democrats. But the reality is that the status quo is clearly deeply harmful.

And the rise in anti-Palestinian racism, Islamophobia, and anti-Semitism that we've seen here since October 7, I mean, all of these things, again, feel very clear to people like us, but I think there's a huge narrative shift that has to happen. And unfortunately it is not going to come without a real reframing of understanding of how Jewish safety and Palestinian freedom are connected in this moment. And it is on Jewish organizations to do that. And it is also on non-Jewish organizations to be willing to grapple with that.

Sarah Leah Whitson: With this increasing divide in public opinion, which is increasingly critical of Israel and its policies with respect to Palestinians, versus the role of organizations like AIPAC and the tremendous resources they bring, there seems to be a very glaring division between public opinion and the power of money. While government employees are capped at $50 for gifts they receive, politicians themselves can receive millions in political contributions.

How can we address this problem? What kind of conflicts of interest has it created? And how does this political giving influence politicians versus the limits on illegal gifts to government employees? Mohammed and Josh, can you comment on that?

Mohammed Abu Hashem: When you look at the policies our government officials have created for their own service departments, it's clear that the effects of money in politics undermine their ability to serve their oath without prejudice. For example, policymakers have established clear ethics guidelines for accepting gifts, whether from entities or foreign governments trying to gain favors. As you stated, the State Department has a policy where anything higher than $25 must be reported. Gifts or donations above this threshold can sway a member to provide favors to those donors, which violates their oath to serve in their appointed position.

Additionally, the military has a similar policy; personnel in the military have a guideline of $375. I've seen and have served on courts-martial where military members accepted such gifts and granted favors in contracts to certain donors in exchange for trading information or intelligence that undermines our national security. These members are punished under the Uniform Code of Military Justice for accepting money that's less than 1% of what our own politicians might accept from donors.

It's impossible for any politician to claim they perform their duties to the people and uphold their oath of office to our constitution when they accept donations ranging from $100,000 to $2 million or more in monetary contributions or other means. In my opinion, our elected officials are in a public servant position to serve the interests of the American people. However, there is a higher probability that they serve the interests of donors, lobbyists, or corporations, rather than the people they swore to serve.

Josh Paul: I would add a couple of things to that. I think I would first of all note that what we have, in many ways, is a legal problem, first of all, right? That it is not necessarily illegal. In fact, it is very legal, particularly after Citizens United, for big-dollar contributions to be given to candidates and campaigns. And that is certainly a problem. I also, at the same time, don't want to overstate the issue. I think that, you know, even if we got rid of that rule or fixed the role of money in politics, that is only one of several reasons why we are stuck where we are on US policy and politics towards Israel. But it is a big part of the issue.

You know, it's something I've been thinking about in the context of yesterday's conviction of Senator Robert Menendez, who was found with gold bars worth $150,000 in his house that he had received illegally, and we can now say this because he's been convicted, from foreign governments to impact US foreign policy. I actually testified in that trial back in May. And as I was sitting there testifying about, you know, the—let's be clear again—illegal role of money in that politics of money in the senator's considerations, you know, I was also very aware that he has received over a million, more often closer to a million and a half dollars a year, through legal political contributions from, you know, various sources in the time, you know, on an annual basis, in the time that he has been in office. And that's not unusual. Most members have received millions of dollars in political contributions. So I think that until—you know, what we have here is ultimately a legal problem. And until we fix that, it is very hard to fix the politics of the thing. The final thing I would say on this is, again, unfortunately, that this is the system we have now. And if we want to change this system, we have to play within the system. We cannot just stand outside and say, oh, you know, money in politics, and isn't it terrible? Yes, it is. But it's also the way things work right now. And that's the way I think we need to organize if we're going to have an impact.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you, Josh. I want to turn it over now to audience questions. I certainly don't think we're going to get to all 98 comments and questions in the chat. But first, I just want to open it up to the audience. If anyone wants to ask any of the speakers a direct question, why don't we provide that opportunity right here? And in the interim, I will try to sort through the 98 questions and see which ones I can direct to the panelists. Tremendous interest here. But let me just respond to one question: we will be making this recording and a transcript of the session available on our website, dawnmena.org. Please tune in for that so everyone will be able to have access to everything we've shared here.

With that, I guess I will just randomly call out a few people raising their hands. Then I'll go back to some of the written questions.

Audience Member 1: Hi, my question is this:

We've had reports of people within the State Department raising concerns about the whole situation throughout this process. We've had reports from reporters in DC and those who have happened to be in-post, who have directly raised what I think they internally call a dissent to Secretary Blinken. And nobody has, you know, he doesn't seem to have responded to that. And obviously everyone's not going to quit their job over this, right? People have families to support and separate obligations. But can you comment a little bit on how that process works? And what happens if the internal leadership in the State Department continues to ignore it?

Stacy Gilbert: Sure. Yeah. So in the State Department, there's a long history of dissent channel cables. If you have a dissent or a problem with a policy, you explain that.

There have been a number of different approaches people have taken on this in the State Department early on in this conflict, with many people signing on to a single dissent channel cable or memo. Now more people are writing their own memos. When those are sent forward, there is a commitment by the leadership at the State Department to engage with the person or people who sent that dissent memo.

We don't know how many have been sent. But I encourage people in the State Department to definitely make use of that, regardless of what your position is, whether you're working on the conflict or not.

If you have a problem with this policy, and clearly a lot of people do, it helps to write it out. It helps for yourself also to be very clear about what you think the problems are and to, very importantly, posit a way to change that.

The more people who do that, I don't know that it will make a change, but I've found in my own process of raising my problems with this that I have had a lot of engagements with senior leadership. And I think I would say there is a lot of sympathy for this position. But, you know, that and five bucks will get you a large coffee at Starbucks. Right now, we haven't seen it move the needle in a meaningful way in terms of policy. But that doesn't mean you shouldn't do that. And I would encourage others outside the State Department to look into whether there are similar channels that you can use in your own agency.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Actually, it reminds me to ask Tariq a quick question that I was meant to ask him.

And really, it is about those red lines. We heard Alex and Stacy describe their red lines. And there are so many people in government who obviously do so because they want to serve their country. But practically speaking, they have to pay the mortgage and pay for daycare and everything else. But, you know, from your point of view, what do you think is a red line that no one could justify crossing to remain in position? What would be your message to all your colleagues and friends and associates serving in the government and the military today?

Tariq Habash: Everyone really does have a different level, what that red line means to them. For me, as a Palestinian American, it was the near daily dehumanization of Palestinian lives and watching our weapons that we provided unconditionally cause the deaths and destruction of so many people and civilian infrastructure.

For other people that may not be a red line. Because at the end of the day, you know, I worked with the Department of Education. I wasn't working primarily on this issue. And I was coming at it from an educational perspective, what was happening on college campuses with the protests. And I think for the question, what is a red line that like no one, what is like the red line for anyone. And I think what it really comes down to is what you're able to do in the context of the current circumstances, and what allows you to be able to sleep at night.

But ultimately, so many of us working in government are not the decision makers on these issues. And I think an important red line for people to consider is how is the work that you were doing day in and day out, contributing to the continued harm to other people, and in the context of our role as American officials? How is it affecting in any way possibly negatively, the impact that it is having on American society and Americans, and American national interests?

I do really want to emphasize that as representatives of the American government, it was our duty to do what was best for our constituents and for the American government and for this administration. But in many of the cases that I personally faced, it felt like there was a difference between serving the American people, and falling in line with what the President was really pushing in terms of policies, and how that undermined America's status across the world, and how it actually made Americans here at home less safe. And I think for me, that was a very clear red line that I think was important to contextualize being at an agency that worked on domestic issues in particular.

Sarah Leah Whitson: I want to turn to a question that was posed in the chat. And then I'll open it up to the audience again.

I guess, to the panelists, and maybe Josh, who can handle this question: Are you aware of any efforts at the State Department to assess steps regarding individual legal risks in terms of aiding and abetting liability, given that there is now a case pending at the International Criminal Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity? Aiding and abetting liability is a specific provision of the Rome Statute.

Josh Paul: Several governments and bodies have already assessed arms transfer risk standards with respect to weapons to Israel, which are really quite similar to what is outlined in CAP policy and the Convention Against Torture policy. How are these decisions factoring into US arms transfer decisions? So, I can give you my understanding based on pretty contemporary conversations with people in the State Department who are involved in these issues.

In the context of the Saudi led coalition war in Yemen, there was actually a legal memo that was developed, produced and sent up the chain. Never finally approved. But that went around very broadly and warned of legal liability for individuals as a result of their complicity. That happened because there was a very brave lawyer who drafted that and sent it up the chain, and sent it around. That person no longer works at the State Department, in part because of that.

And there has not been, in this current context, a similar effort, in part because it has not been called for by senior leadership. And that's normally what it takes, is for a senior official in the State Department to say to the Office of the Legal Adviser, Hey, what are the legal risks here? What should people be aware of? So what there has been, instead, is individuals, I think within the State Department, and certainly in the arms transfer process, who are aware that there could be legal liability for them, even acting in their official capacity, who have asked the question of lawyers within the Office of the Legal Adviser, Should I be concerned? Is there legal liability? And my understanding, sadly, is that the response has rather depended on who they ask. That some of the lawyers will say to them offline, Yes, you probably should be concerned to be honest with you. And here's what you should be thinking about. Others will not answer the question, or will say no, you're acting in an official capacity, don't worry.

I think that sort of scattershot approach is pretty appalling service to lower level employees. Frankly, I think it is one thing if you are the Secretary of State, and you have the wealth, and you know, the legal counsel that is there to support you. It is another if you are a junior licensing officer, let's say, who is facing the same questions and the same moral challenges, and doesn't have that deep bench of legal support. So I think the State Department is not serving, particularly its junior employees very well, in considering these questions. And then I'll just close by saying I think more broadly, there is clearly legal exposure, both within the US domestic system and the international system, and let's say also, third party legal systems, cause some of the crimes that we are talking about here have universal journal jurisdiction and can be charged in foreign courts.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thanks for that, Josh. My organization has repeatedly warned the administration that they do, in fact, face liability for aiding and abetting crimes in Gaza. I think it would be beneficial for the rule of law and accountability if this were addressed.

I want to turn to a question in the audience. Please go ahead and ask your question.

Audience Member 2: I wondered if anyone could answer a general question I have. What seems to be the reason—psychological, political, or otherwise—why so many officials, particularly in the Democratic Party, turn such a deaf ear to criticisms of Israel and an honest evaluation of what Israel actually is?

Even in light of the massive political upsurge calling for that kind of evaluation, there always seems to be a contrast. For example, the treatment of Ukraine versus the treatment of Gaza.

So I wonder if anyone could answer that.

Harrison Mann: I can jump in quickly, and I'm sure the rest of the panelists will have more to add. I'll just say, you know, have you heard of the Palestinian AIPAC?

Many people who are not deeply engaged with the Middle East issue, including a lot of well-meaning individuals, have had their views about the region and Israel shaped by lobbying groups and academics. There's been a concerted effort to present a possibly inaccurate understanding of what Israel is and what it does. So, many people, including members of Congress we've talked to, have only been exposed to critical views of Israel recently. Before October 7, they had not seriously considered alternative perspectives.

There's also a significant number of people who are ideologically aligned with Israel. They understand the situation well but believe that the actions taken are a necessary cost to support an ally or to achieve stability in the region. At the highest levels of our government, those making decisions are often both sympathetic to Israel and convinced that they can exert influence on the Israeli state, despite evidence to the contrary.

That's a very abridged explanation.

Tariq Habash: And I'll just add one brief additional comment: It is ultimately rooted in anti-Palestinian racism, which is a more acute type of racism and discrimination against Palestinians and those who support the Palestinian cause and freedom. The reality is that this racism is rampant and has been pervasive in how Palestinians are treated, how they are discussed in the media, and how our government officials interact with them. It's something I experienced firsthand while I was in government and throughout my life growing up in the Midwest.

Sarah Leah Whitson: We have tons of questions coming in. So I'm going to move on to the next one, if that's all right.

We have a question from the chat that I think will be of great interest to many participants. Can one of you walk us through the process of leaving the government? How do you give notice versus making a public statement to the media? How do you figure out the timing of that? What are the steps that one should take within your office or agency first before actually giving notice?

Please walk us through your experience and maybe what you've learned from your experiences about the best way to go about this to have the most impact.

Tariq Habash: I'm happy to start with the caveat that I think a lot of us have had very different experiences and how to approach this, particularly because some members of the military have an actual separation process that takes a longer period of time. Foreign service officers who are living abroad also have other considerations to take into account, especially if they're in U.S.-based housing. These types of factors are all things that different people have to consider, and they were not factors for me to consider.

For me personally, I did provide an extended period of notice to my direct supervisor and to the Assistant Secretary. I had conversations with nearly every Assistant Secretary, Undersecretary, and Secretary within my building—people with whom I had personal relationships. This made my situation somewhat unique. I also consulted a lot of people whom I trusted, including friends and family.

And ultimately, I think, for me, it was important to write a letter. I had left fairly early into the conflict, and it was crucial for me to articulate, particularly because I was not working directly on these issues but was at the Department of Education. It was important to contextualize why it was significant for me to publicly resign.

I had support from colleagues with whom I had really close relationships. I did outreach to the media and press, which is not something that everyone has done, but I think all of those steps were important. Additionally, I took personal and digital security very seriously because I did not know what to expect. As a Palestinian American, I was unsure what the backlash would be. Fortunately, I had a positive support system once I left, including many former colleagues who reached out to me directly through social media, email, and text to check in and make sure I was doing well.

I'm extremely grateful for all the support I received. Not knowing what it would feel like or what it would look like as a Palestinian American leaving the government over U.S. policy on Israel-Palestine was a really scary thing. So, I took some precautions to make my family feel safer.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Anyone want to add to that? All right, I will then ask an audience member to please ask your question. Unmute yourself first.

Audience Member 3: The Global South is in a dramatic shift towards the BRICS and other forms of independence from the US and British colonial policy dominated by the dollar. The US government needs to join them in their quest for development, which will benefit our economy greatly. This is also how to stop the Gaza atrocity. The Schiller Institute and the International Peace Coalition have for decades been fighting for an Oasis Plan for Southwest Asia as a whole. Do you agree that cooperation for mutual development is the way to go for Gaza and Israel, and how can the US be involved in this movement for peace through development? I appreciate you taking my question.

Alex Smith: I think you raise a good point that the future is very uncertain. What we've been discussing, and what I've been talking about, involves the dismantling of many systems we used to rely on, such as the rule of law, which were meant to protect against massive crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. We are witnessing the US giving up its leadership in that arena. I wonder if the future will be more BRICS-centric, with countries like South Africa, which is bringing the ICJ claim against Israel and standing up for principles of human rights law, playing a significant role. However, it is indeed uncertain and quite frightening not to know where we will stand in the next 10 to 20 years, especially as we have relinquished our role as a leader in human rights.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thanks for that. Alex, as we are coming to the end of our session, I know we have far more questions than we will be able to get to. I want to urge everyone to please email us at advocacy@dawnmena.org. We will follow up with the panelists to get all of your questions answered. If you could direct your question to any specific person, that would be very helpful.

But before we wrap up, I want to take one more question from the audience.

Audience Member 4: I would like to start off by saying thank you all for your courage and taking this huge step to leave prestigious and amazing positions within the government. You will never be forgotten, and your motivation is an illustration for all of us, especially those of us who are still in government.

My question is, if you were to raise concerns about certain cooperation with a specific country overseas, and at the point of making, as you know, that you're raising awareness within the Georgia Department about something that possibly can entangle the department in future problems, especially with IC and so on. And at the beginning, you were told that it's good that you have done that. And then later on, you start to see retaliation in different forums, within your position that hinders you from doing your job, which will be reflected as a bad review at the end of the year. Would you consider resigning at that point? Or would you consider taking the legal chances of actually bringing that up as discrimination or so on?

Josh Paul: So, I mean, I think all of us probably have an answer to that. Maybe I'll just start quickly, which is to say, first of all, in that sort of situation, well, let me back-up. First of all, you know, there are protected channels, and there are channels that are not protected. But let's be honest, there are plenty of ways for retaliation to occur, even when protected channels are used, where it can be very hard to demonstrate that it is retaliation, but I think we need to be aware of that.

I would encourage someone in that position to certainly consult with a lawyer who is an expert on those matters. I would also encourage them to reach out to people who have resigned to see if there's any assistance that we can provide. There are also options to speak, for example, to inspectors general, and to others who look specifically at these sorts of issues, to identify if there are concerns there. I will say that I have heard of multiple cases like this.

Without revealing any details, I'm aware, for example, that there are some people who are involved in lawsuits specifically because they have been retaliated against over this issue or over related issues of identity.

So, I think the important thing is to find the support that a person in that situation needs and to do so certainly initially in a way that is confidential and, honestly, not to trust the system; the system will screw you over. And I think the important thing is to get outside counsel from both legal experts and from colleagues and friends who may have some insights.

Mohammed Abu Hashem: I want to add that it is the same thing when I received a lot of phone calls from some of the military members I told them about when they asked me if they should step aside from their military careers. And I always tell them, it's all dependent on the moral injury that they are suffering through, right, we are taught from day one what is right and wrong, by policy, by black and white. And when we advise on these kinds of issues, and it's been ignored, that's when you have to realize yourself, and that's when I think I realized myself that no matter what I tried to do, no matter how I tried to use my voice as a Palestinian American, they were not willing to listen. So what's the point of being elected as an advisor? When nothing I say matters? At that point, I knew that I had to step aside because I wasn't making an impact from being in the service. So I needed to make an impact in a different way.

Harrison Mann: I want to just add on to that briefly. If you're in this kind of situation where you are facing discrimination or are facing some kind of action at work because of your position, one, my general advice to anybody in this effort, especially if you're in a federal agency, make sure you're taking notes about what's happening and email your best friend or somebody with timestamp records of this person did this. Whether this is for legal purposes later, or whether you want to share this publicly, that's going to be very important. I think when deciding whether you want to try and use internal, you know, institution-specific means, like the inspector general or something to resolve your issue.

Think about what if you don't get your way and don't get the change you want? What direction you might want to change this? Or what direction you want to take this in the future? Is this potentially going to end with you resigning? If you resign, you're going to want to do it publicly. If you resign publicly, are you going to be able to show that, hey, I tried everything I could from the inside, and they were unable or unwilling to help me? Or they even made it worse? These are not rhetorical questions. But I think important considerations when you decide how much you want to try and work within the system, versus working without, and just factor that into your calculations.

Sarah Leah Whitson: I think that really is a reflection of how much interest and desire there is to hear what you guys all have to say. So I want to be courteous to our audience and go to one hour and 45 minutes, but also not take too much of your time. Let me just say before I turn to another question, that, again, you can find the transcript and a copy of this video on dawnmena.org or our website. You can send further questions that you have to advocacy@dawnmena.org. And I should say we are having a gala dinner on October 2 in Washington, DC, at the National Press Club, where all of the attendees here will be invited to attend as our honored guests at the event. And so if you attend our gala dinner on October 2, you can meet these folks, I think many of whom are heroes in our eyes, live and in person. With that, let me ask an audience member to ask your question.

Audience Member 5: So I guess my question for all of you is, what advice do you have for those of us who have been advocating for Palestine, for human rights, for the past, you know, 10 years, for example, and are having trouble getting jobs because of the corporate practices of not hiring people who are likely to blow the whistle? What advice do you have for us?

Harrison Mann: I'll jump in now, because this was something that I thought a lot about. And, you know, I'm still unemployed right now. And I think everybody of the dozen of us who resigned is probably going to be okay, but this taking this position as you point out, like it, it may involve some sacrifice. And the way this is, this is probably cold comfort to you. But you know, the kind of way that I reassured myself was like, well, I don't want to work anywhere that's not going to have me for taking this position. And I know that comes from a position of privilege. But I think that's the best I can say for now. And I'll see if the rest of the group has more to add.

You know, I don't know everyone's calling in from around the world; a lot of us, including me, are based in DC. I wanted to work in DC, and that's a town where people really care about this. And so I'm going to look for somebody who feels the same way that I do, but it's just the best that I can say.

Sarah Leah Whitson: Thank you. I am trying to see who else is up. Hello, can you unmute yourself?

Audience Member 6: Well, my basic question really was about the danger of the Trump administration coming in and making things much worse. What would you recommend in terms of, you know, we have four months before the elections, and I'm wondering if you all are still advocating for a Democratic victory in November 2024?

Sarah Leah Whitson: Let me just chime in by reiterating that DAWN is a 501(c)(3) organization, and we ourselves do not endorse political candidates. But with that, I can turn it over to the panelists to say whatever they want.