Muhammad Kamal is a former research assistant at DAWN, where he worked on human rights protections in Egypt and across the region.

Former Egyptian political prisoner Noha Kassem does not hold back when asked if she has a message for Egypt's government, which forced her into exile in 2019. "My message to the coup regime—and I hope you keep this wording and do not change it to 'Egyptian authorities'—is that they are criminals and what is happening in Egypt is a crime against humanity and a crime against the homeland," she said in an interview with Democracy in Exile. "History will hold you accountable."

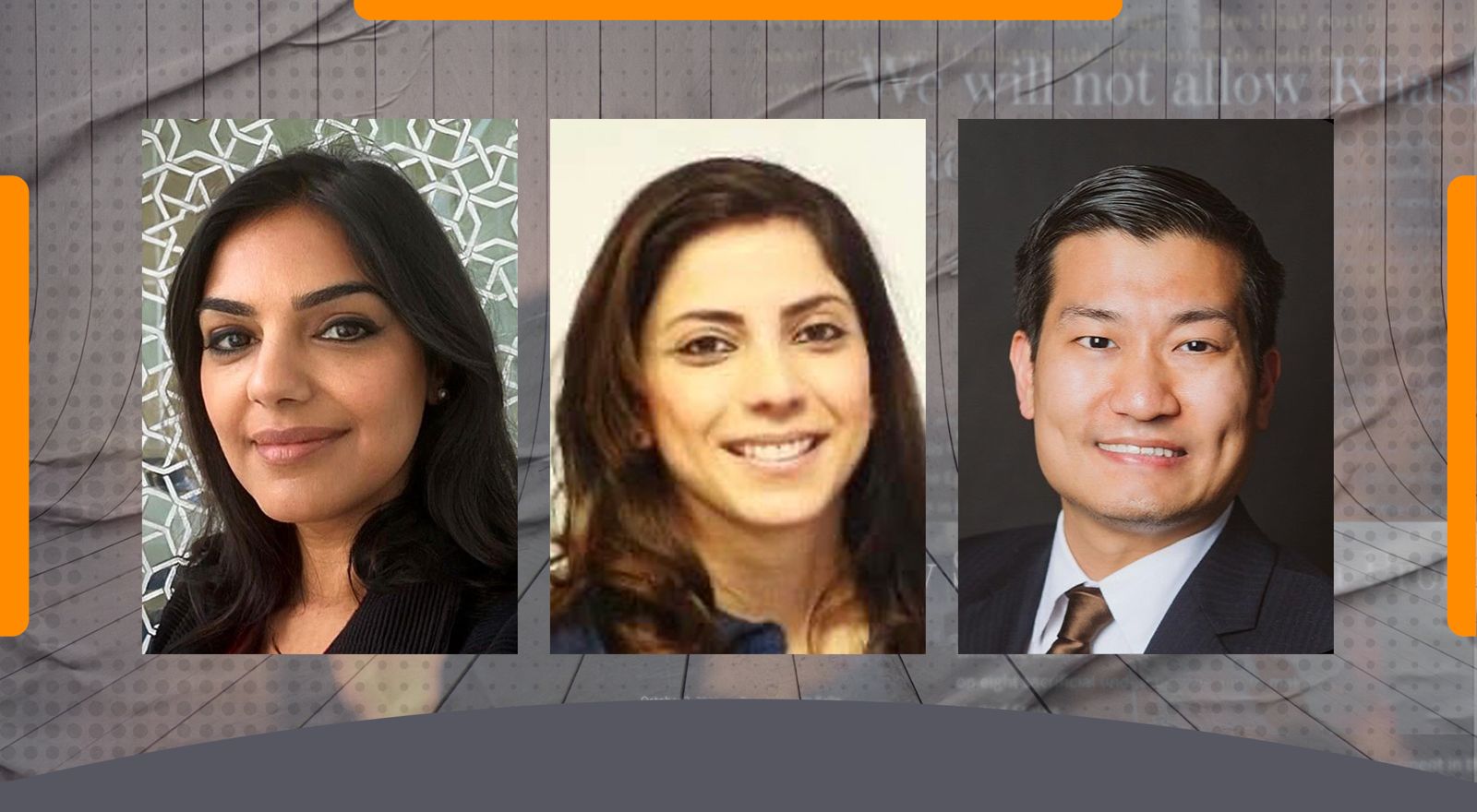

A doctor and psychotherapist, Kassem was arrested in Egypt in January 2018, on charges of assaulting a judge; she was acquitted a month later. In January 2019, she fled Egypt, eventually settling in Istanbul like so many Arab political exiles.

Kassem is also a longtime political activist who coordinated a mobile field hospital in Alexandria throughout the 2011 popular uprising against President Hosni Mubarak's regime. She later took part in the protests in Cairo's Rabaa al-Adawiya Square in 2013 against the military coup that ousted President Mohammed Morsi a little over a year after his election. Under the regimes of both Mubarak and Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, Kassem provided support as a psychiatrist to former detainees who had been tortured while in the custody of Egyptian police, as well as to their families.

Kassem lives with her three daughters in Istanbul. Her husband, Mahmoud Abdel Momen, owned a medical supply company and was the elected head of the Syndicate of Scientists in Alexandria, until he was arrested in March 2015. "He was forcibly disappeared for a whole week," Kassem recounted. He was being held by a military prosecutor. "Since my husband is a civilian, I thought there was something wrong."

He was accused of being involved in the bombings of government buildings in Alexandria, charges he adamantly denied. "One of the strangest things is that during the investigation by the prosecution, my husband asked the investigator about the dates of these bombings that he was being accused of," Kassem recalled. "The military prosecutor responded by saying he did not know the dates of these bombings. From this moment on, we were convinced that everything was a play."

In December 2017, an Egyptian military court sentenced him to life in prison. "There was no evidence that my husband was involved in any of these incidents," Kassem said. "His sentence fell on us like a thunderbolt."

The following transcript has been edited lightly for length and clarity.

What is happening in Egypt is a crime against the freedom and humanity of all Egyptians, not only inside the prisons but throughout the country where every Egyptian has their rights violated.

- Noha Kassem

What was your life like in Egypt before the 2011 revolution?

Life in Egypt before the revolution of Jan. 25, 2011 had become very difficult. During my university studies, I participated in demonstrations in support of the second Palestinian Intifada. I hoped to improve Egypt's situation through participating in the parliamentary elections in 2000 and 2005; I dreamed of positive change for my country. But all these efforts and dreams were not realized.

When I enrolled in the university, I joined the Islamic youth movement and got involved in the medical field in Alexandria. At the end of my graduation from the university and during medical training, I was involved with the Life Makers Foundation [an NGO in Egypt] and was responsible for its human resources and development. I was one of the main activists present in all the demonstrations at Alexandria University, including in April 2002, when we were assaulted by a police force leading to the death of one university student.

I was active in the Egyptian Medical Syndicate after graduating from medical school. As young doctors, we wanted to reform the medical system in Egypt and provide quality health care, but we always ran into corruption and the dysfunctional establishment in Egypt. Our attempts at reform were always hindered by corruption.

Reform was impossible, which I think was the motive for the revolution on Jan. 25, 2011. From our first day on the street, we felt that we had done everything we could to either fix the country or die. And that was how we felt throughout those 18 days of the Egyptian revolution.

I did not demonstrate during the revolution in Tahrir Square in Cairo, but I was participating in Alexandria, where I was the coordinator of the mobile field hospital and a member of the Medical Syndicate. We set up the field hospital because of the need for doctors to treat the protesters who were injured by police forces. We provided a small bus containing treatment and first aid equipment, and we increased its capabilities according to the needs. We roamed with the demonstrations on the streets of Alexandria until the day Mubarak stepped down.

How did the 2013 coup affect you and your family?

After the revolution, there was a qualitative transformation in political activism. The revolution changed things. Everything that I mentioned about the pre-revolution period were desperate attempts to fix the situation. But we always faced the barrier of state corruption. After Jan. 25, we were moving on a wider horizon; there was no longer this barrier of the state actively blocking us.

After Mohammed Morsi assumed the presidency, we began to communicate with his team and share our projects and ideas, until we were surprised by the coup on July 3, 2013. Everything stopped after the coup.

I was trying to keep my free will. I had voted for Morsi, and I was not willing to accept a military coup to topple the revolution and kill my will and dreams, eliminating my voice and those of millions who had elected Morsi—irrespective of how unhappy we were with his performance during his one year in power. Under Morsi, progress was slow and many things were not implemented, but we felt real desire and will to achieve change. Morsi was our choice and the result of our votes. If anyone wanted to change Morsi, then they should have had to choose the same means—the ballot box—and by presenting a different project on which basis people can then decide with their vote. But it was unacceptable that change came on the back of a military tank that canceled my voice and that of millions.

I was one of the first to join the Rabaa Square protests. Together with my husband, I was the coordinator of the field hospital there. We were keen to defend our country's freedom and not let go of these sacrifices. We did not want to return to the era of the rule of the tank and force, of autocracy and one voice.

We participated in the entire sit-in, except for the last three days after Eid al-Fitr, because we had to return to our house in Alexandria and look after my three young daughters. I participated in the Rabaa sit-in and worked at the field hospital to treat the injured for the sake of my daughters. I was raising them on the values of freedom and justice, and I did not want them to live in a society without either of these. My daughters were nine, seven and five years-old at the time, and I had left them in the care of my mother so that I could defend their rights and prevent my country from going back to pre-2011. I was not at the Rabaa sit-in when the cruel, brutal dispersal of the protesters occurred. My fellow doctors who were at the field hospital later told me about the ugliest things a human could imagine.

How did it affect your work providing psychological support services to detainees and their families in Alexandria?

After the military coup in 2013 and the arrests, cruelty and criminality of the Egyptian government, army and police, large numbers of Egyptians, including those around me, were suffering from serious post-traumatic stress. Since psychiatry is my profession and I have a lot of experience in it, I started to provide psychological support to those affected by events in Egypt. This support was divided into two: the first was receiving anyone in my private clinic who needed help or suffered from depression or post-traumatic stress. I provided this service free of charge.

The second thing was training families of detainees and the injured as trainers through a course called trauma recovery, so that they can provide psychological support themselves. The magnitude of the damage inflicted on Egyptians was so great that the number of existing psychiatrists alone could not deal with all the cases.

From the cases I have seen, I can confirm that many young men and women were subjected to inhumane torture at the hands of the army and police, leaving behind deep psychological scars and wounds. I was doing everything I could. I sometimes met families of detainees while visiting my husband in prison.

How, when and where were you arrested?

I was arrested and charged on the day my husband was sentenced by the military court in Alexandria with families of other detainees waiting to hear the verdicts. We were surprised by the harsh sentences—execution, life imprisonment, or 10 to 15 years imprisonment. As a result, many families were traumatized. People started crying, screaming and collapsing. The soldiers started to assault the collapsed women just because they were crying and screaming outside the courthouse, which was inside a military base.

I tired to defend the women being assaulted by the soldiers, and as a result the soldiers started beating me. I was trying to talk to them calmly and rationally, asking them why they were assaulting us and what we did wrong. I tried to talk to an army colonel who was in charge of the security force securing the court. He knew I was a doctor. I asked him why he was harming the women who were angry because of the verdicts—why not leave alone and then they will go home? The result was that I was assaulted very violently. The driver who drove me to court was arrested because he tried to protect me when he saw the soldiers assaulting me.

We were surprised the next day that the authorities had filed a case against me and the driver, accusing us of assaulting the judge. We weren't even allowed to approach the court, which was several kilometers inside the military base. My only role was to calm the families of the detainees, mothers and children crying because their relatives were sentenced to death and imprisonment.

When I learned about the case against me, I was getting ready to travel outside Egypt. I was arrested by National Security forces from the street on Jan. 28, 2018, immediately after receiving my passport. They had issued a warrant for my arrest. I was transferred to the Amreya police station in Alexandria, and presented to the prosecution. I was surprised that the case was referred to an emergency Supreme State Security Prosecution. I was transferred to al-Abaadiya women's prison in the city of Damanhour. I stayed in prison for about a month and was presented to the sentencing hearing, where the judge acquitted me. The authorities kept me for another week between the National Security Agency and the various police stations in further attempts to harass me. They then released me on March 6, 2018.

Compared to the detention conditions of others, mine was easy and simple. I had treated detainees who suffered the most horrific forms of inhumane physical, sexual and psychological torture. Even so, I was held in a solitary cell without a bathroom for two whole days. I was intimidated and threatened by National Security and prison officers. They treated me as a very dangerous person, and sometimes they prevented people from talking to me.

I was then transferred to a cell holding 32 other detainees and measuring three by four meters, with one bathroom that did not suit the needs of the women. I was locked in the criminal ward, which was filled with cigarette smoke that made me sick with asthma. I came out of prison with a severe bronchial flu and had to use a ventilator three to five times a day, and I was taking a lot of medication to be able to breathe. During the last days before I was released, I couldn't move because of the severe illness. I slept in a tiny area that is not enough for a person to spend the whole day, and I was not allowed to go out in the sun.

As for violations I personally witnessed inside the prison, I saw some of the detainees locked in solitary confinement for months, like the one where I was imprisoned for two days. One of the political detainees who was pregnant was imprisoned in a solitary cell without a bathroom, even after delivering the child.

The conditions of detention in Egypt are completely inhumane. There are female detainees who have been sexually assaulted at the National Security headquarters who told me about these attacks so that I could help them recover. Places of detention in Egypt do not take into consideration women's needs. Some cells do not have bathrooms, and if there is a bathroom, it is a hole inside the ground. In al-Abaadiya prison in Damanhour, water was only available five times a day for 15 minutes, with a total of no more than an hour and a half, and the rest of the day detainees were without water.

If we are in forced exile, struggling to provide a decent life for ourselves and our families, the Egyptians who stayed in Egypt do not have even the luxury of living.

- Noha Kassem

After your release, you decided to leave Egypt. Why and how did you leave?

After my release, I agreed with my husband when I visited him in prison that I had to leave the country with my daughters. For the first time in our lives, we made a decision to leave Egypt, which was the logical decision in such circumstances. My hardest day was the day I said goodbye to my daughters and my family despite not knowing in what form and manner I was leaving. For many months, I was unable to retrieve my passport, mobile phone, ID card and other belongings, which were confiscated when I was arrested.

When I failed to retrieve my passport by all legal means, I realized that this could perhaps indicate that I was going to be arrested again. I was indirectly informed that the authorities might re-arrest me and this time I might not be acquitted. I decided that it was time I left Egypt, which was one of the most difficult moments of my life. I left Egypt on Jan. 28, 2019. I had to flee the country by being smuggled through southern Egypt to Sudan. I arrived in Khartoum on Feb. 1. Then I left for Turkey in May 2019. My daughters were able to catch up with me at the end of July 2019.

The way I got out of Egypt was the long and difficult road that many opponents and activists are forced to take, because the regime in Egypt is keen on keeping all Egyptians monitored or imprisoned. If we say that there are many Egyptians detained inside prisons, the rest of Egypt is detained outside prisons—because the regime not only arrests people, but also prevents them from traveling abroad and turns airports into places of detention. A month before I left Egypt in December and January, the regime had arrested a large number of Egyptians trying to flee at the airport.

Are you currently able to communicate with your husband in prison?

After leaving Egypt, communication between me and my husband was cut off because there is no permissible or legal way to communicate with him. The prison administration does not allow letters from political detainees to be written or received. There is no way to for us to communicate.

What difficulties do you face as an activist and a doctor in exile and a mother who has to raise her children without their father?

Life remains difficult, and I am in a strange country. I am still trying to learn Turkish. I try to stay in touch with people in Egypt, but it is different raising my daughters without their father, family or community support.

My daughters suffer from the lack of relationships with school friends and the community. The first period after their arrival to Turkey was very difficult in terms of adaptation, especially since we felt compelled to leave Egypt and did not leave it voluntarily. For me and for my daughters, life in Egypt is better, although there are many who see Istanbul as a beautiful city, and this is true—but we did not leave Egypt voluntarily to visit or stay in Istanbul. We left Egypt for Istanbul to flee for our freedom and religion and to maintain our security.

There are no words to describe how I feel about not seeing my husband all these years. I talk to my daughters about their father all the time so they don't forget him. We constantly watch videos and look at photos of us so that they would keep their father alive inside them. I make sure that my daughters meet my husband's acquaintances and friends to tell them about their father, his qualities and his good deeds. If my daughters today don't have a chance to live with their father, they should not be deprived of their childhood memories of their father and his friends' memories of him.

If you could deliver a message to the families of political prisoners in Egypt, what would it be?

My message to them is to stand firm and hold on to the memory of their families. Be the voice of your detained families and express them. If the unjust ruler arrested your family—to hide them from this world, so that they would not be allowed to liberate Egypt—be their voice and remember them to disturb the oppressor who imprisoned them. Remind others that there are people who dreamed of freedom for their homeland and are still imprisoned and waiting for the moment when Egypt is liberated. Support your friends and relatives who are detained in Egypt. The families of detainees feel great pain. But the detainee inside the prison in a solitary cell and deprived of all means of life, and those who are subjected to torture, they need all our support. Be their voice and support them at every visit, and tell them that you are with them and waiting for them and we will never forget them—and we will not allow the world to forget them.

How about a message to exiled activists and politicians?

My first message to them is that I appreciate the pain you feel and understand the meaning of forced exile. I know that although we enjoy some security in the countries to which we were exiled, we are still denied the freedom to return home. We do not feel completely free because of our inability to return to our homeland. We know that those who are still inside Egypt have lost all freedoms, even the freedom to breathe. We should not forget them. If we are in forced exile, struggling to provide a decent life for ourselves and our families, the Egyptians who stayed in Egypt do not have even the luxury of living. Be responsible. If you succeeded in getting out of Egypt, there are others who did not. Make sure to not waste energy on useless things. Use your strength to work for our return to our country and the liberation of millions in Egypt. Know that the life of those living in exile is not easy or simple and that they are suffering. Despite all this suffering, you still have the partial freedom to liberate Egypt. Don't waste time. Don't let ongoing conflict make you forget the main goal of our exit, which is the freedom of Egypt.

What do you say to the international community? What do you think they should do?

My message to the international community and international human rights organizations is that what is happening in Egypt is a crime against the freedom and humanity of all Egyptians, not only inside the prisons but throughout the country where every Egyptian has their rights violated. You know all this and have seen the videos and testimonies. You have no excuse.