Terry Anderson is the executive director of Cartoonists Rights, a nonprofit founded to protect the rights of editorial cartoonists under threat. A professional cartoonist of some 30 years’ experience based near Glasgow, Scotland, he was a founding member of the Scottish Cartoon Art Studio and a past president of the Scottish Artists Union. He was the first non-Francophone to receive the Prix Gérard Vandenbroucke at the Salon International de la Caricature, du Dessin de Presse et d’Humour for his services to cartoonists.

Nearly a decade ago, Islamist extremists embarked upon a campaign of terror in the city of Paris, starting at the office of Charlie Hebdo, the satirical French magazine. A dozen people were killed in the attack, among them five of France's most prominent cartoonists, and in the week that followed, memorials of a scale not seen since the end of World War II ensued, with world leaders, arm-in-arm, declaring "Je Suis Charlie."

The shadow of January 7, 2015 is long, and yet a new set of anxieties have supplanted its effects. When asked, cartoonists' chief concern today is not attacks from fundamentalist terrorists, but rather aggression from the state and its agents, official and otherwise. Across the Middle East in particular, these threats are most pronounced. But they are also now looming in the United States with Donald Trump's return to power and a bill moving through Congress that would grant the executive branch vast new powers to harass civil society in the name of fighting "terrorism."

Cartoonists suffer no more especially than anyone else, but as the work of these cartoonists across the Middle East shows, they can express that suffering with powerful precision through their art.

Seemingly thin-skinned authoritarians do not fear cartoonists themselves, but what their work represents.

- Terry Anderson

Egypt

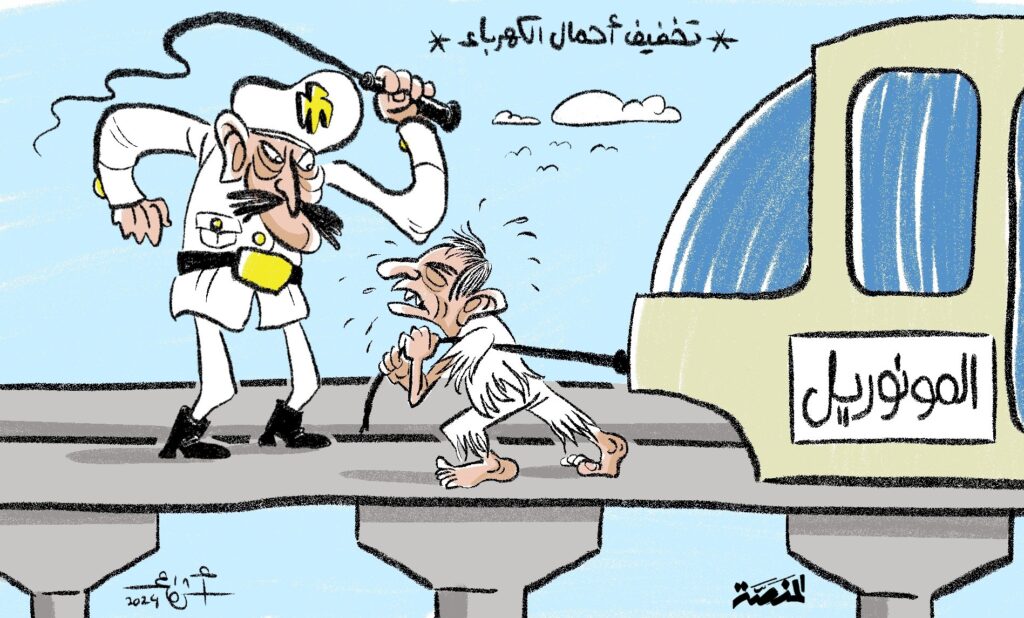

A prime example is Ashraf Omar, a cartoonist for the independent Al-Manassa news outlet in Cairo. In July, Omar was taken from his home by plainclothes personnel; for a time, Egyptian police disavowed knowledge of his whereabouts. In the days prior to his detention, Omar had submitted cartoons about Egypt's economic crises, energy and infrastructure problems—typical editorial commentary. After he was missing for 72 hours, the Egyptian authorities confirmed that he was being held in pre-trial detention on charges pertaining to the "support of terrorism." Since then, his detention has been extended nine times by means of COVID-era video conferences that deny client and defense attorney the opportunity to communicate. Omar's wife can see him for half an hour every 30 days. The cruelty sends a chilling message to Egypt's other cartoonists about the acceptable bounds of their drawings.

Egyptian cartoonists are not protected by their fame or international stature, either. Doaa el-Adl is perhaps Egypt's most celebrated cartoonist, whose work appears in the newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm. Profiled memorably this year in the Draw For Change! documentary series, she has in the past been the subject of two politically motivated investigations by state prosecutors. To this day, el-Adl endures a stream of patriarchal pushback, intimidation and even death threats for her cartoons.

Palestine

As a rule, women cartoonists are burdened with additional gendered abuse and discrimination wherever in the world their cartoons are published. International cartoonists were horrified by the death of Mahasen al-Khatib in the Israeli military's attack on Jabaliya refugee camp in Gaza in October, mere hours after she posted a cartoon decrying the inhumanity of hospital bombings in northern Gaza. A swift campaign led by political cartoonist Gianluca Costantini saw al-Khatib's life commemorated at the Lucca Comics and Games festival in Italy, a prominent comic book and gaming convention that has been running annually for more than 50 years.

Right now, Safaa Odah continues to draw heart-rending cartoons from Khan Yunis refugee camp in southern Gaza, under continued Israeli bombardment and blockade. Her art materials having long since ran out, she draws on the plastic sheeting that makes up her family's tent, posts a photo to social media, then wipes the drawing away.

Based in the West Bank, Mohammed Saba'aneh is the foremost cartoonist focused on Palestinian rights, with a long string of international exhibits, publications and awards to his name. Despite being subjected to the ire of both Israeli prosecutors and Palestinian leadership, Saba'aneh still suffers accusations of antisemitic bias in the West and has encountered pushback even in supposedly safe spaces, such as the bizarre sabotage of his show of work in The Hague in 2019.

Jordan

Across the region, there is arguably no healthier cartoon culture than in the kingdom of Jordan, home to a long-standing and vibrant cartoonists' association. Several leading lights among Jordanian cartoonist are very well-known on the international scene. Yet even in Jordan, cartoonists can be intimidated and ultimately displaced. In 2020, I wrote a letter for Rafat Alkhatib to carry with him during a period of sustained harassment and threats, warning any that might harm him that international organizations were monitoring his welfare.

Another prominent cartoonist, Osama Hajjaj, faced criminal charges over a cartoon deemed offensive to Islam. He was charged under Jordan's sweeping and nefarious "cyber-crime" law, a common tactic in multiple countries to impugn all sorts of activists and artists. When cartoons cross international borders—easier than ever in the social media age—the often-willful misinterpretation can follow, and trouble with it.

United Arab Emirates

Such was the case when Emad Hajjaj, perhaps the most well-regarded Jordanian cartoonist—and Osama Hajjaj's brother—drew a cartoon mocking the UAE's normalization deal with Israel. The long-serving president of Jordan's cartoonist association, Emad Hajjaj depicted Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the powerful Emirati ruler known as MBZ, being spit on by a dove with Israel's flag on it. A splatter on MBZ's cheek was in the shape of a fighter jet with Arabic letters inside spelling out F-35, the advanced military hardware Israel had lobbied the U.S. against selling to the UAE.

Hajjaj was immediately arrested in Jordan and interrogated at length, but the criminal prosecution ultimately petered out. In my view, Hajjaj was used by Jordan as a pawn to placate a powerful Gulf neighbor, the UAE, that is also one of Jordan's key patrons. It is noteworthy that in the same 24 hours as Hajjaj's arrest, Jordan's Prince Ali bin Hussein had tweeted about MBZ, sharing an article critical of the UAE's normalization deal with Israel. Presumably, the prince could not be censured, so Jordanian authorities targeted Hajjaj targeted instead to appease the UAE.

Saudi Arabia

Hajjaj is hardly the only cartoonist who has been targeted for his work in another country. In 2020, Palestinian cartoonist Mahmoud Abbas, based in Sweden, published a cartoon about Saudi Arabia and the collapse of oil prices amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The cartoon, which depicted a man in Gulf Arab dress running away from rolling barrels of oil, went viral on social media, sparking a huge backlash in Saudi Arabia, where it was wrongly taken to be a caricature of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. Abbas received death threats serious enough to warrant a Swedish police report. This hailstorm of harassment was undoubtedly automated in part, using pro-Saudi bots and "sock puppet" accounts on social media, and fits within a pattern of politically motivated harassment of cartoonists.

But few have suffered like Saudi cartoonist Mohammed al-Ghamdi, who draws under the pen name Al Hazza. In 2018, he was arrested and ultimately sentenced to six years in prison after publishing cartoons in the Qatari paper Lusail during the Saudi-led economic boycott of Qatar. As the end of his six-year prison sentence approached earlier this year, al-Ghamdi was handed a truly staggering, further custodial sentence of 23 years. Al Hazza's crime? His cartoons "insulted" the Saudi government.

Cartoonists in America branded as an "enemy within" could end up facing the same threats and abuse from their government as their counterparts across the Middle East.

- Terry Anderson

Seemingly thin-skinned authoritarians do not fear cartoonists themselves, but what their work represents. Because their art so succinctly and readily expresses popular discontent, in a simple drawing, they make themselves a proxy for all who feel the same. Brutalize them, regimes think, and perhaps those still silent will stay that way. Solidarity is extinguished, and with it the necessary precursor for change.

It remains to be seen how the second Trump administration will approach the Middle East and North Africa, and whether Trump's expected isolationist posture will result in a free pass for human rights violators overseas. In the United States itself, Trump has openly called for an assault on civil society, after an election campaign in which he made threats about "the enemy from within." A bill directly targeting nonprofits, which would give the Treasury Department sweeping authority to revoke the nonprofit status of any NGO designated as a "terrorist-supporting organization," just passed the House on November 21, after it was narrowly voted down the week before. The bill, H.R. 9495, was approved mostly on party lines, although 15 Democrats joined Republicans in voting for it.

Organizations like DAWN and Cartoonists Rights, and indeed any other human rights defender in the U.S., could fall foul of such legislation, depending on mutable definitions in the proposed law about what constitutes "supporting terrorism."

The ACLU has warned that bill would "grant the executive branch extraordinary power to investigate, harass and effectively dismantle any nonprofit organization—including news outlets, universities, and civil liberties organizations like ours—by stripping them of their tax-exempt status based on a unilateral accusation of wrongdoing."

The bill now moves to the Senate. If passed, it would surely be weaponized by Trump. Cartoonists in America branded as an "enemy within" could end up facing the same threats and abuse from their government as their counterparts across the Middle East.