Solafa Magdy is an Egyptian journalist and human rights defender. A former political prisoner in Egypt, she was detained along with her husband from 2019 to 2021.

عربي

Three women, each from a different political current in Egypt, and each with her own political orientation and ideological affiliation, met in prison because they were accused of the same crime: belonging to a terrorist group. Destiny brought them together behind bars to start a new journey.

The first meeting was inside a cell in al-Qanater women's prison, north of Cairo. Shams, who belongs to the civil current, met Dalilah while washing their clothes in the restroom area at noon. Dalilah belonged to what might be called the Islamist current (her name is a pseudonym, and she knew me as Shams). Our eyes met secretly, as it was forbidden for female political prisoners to talk to each other. The guards fear prisoners developing friendships, and exchanging ideas and opinions—that it might start a rebellion or a prison strike. Some political prisoners were under order to be separated from their inmates even in the cell, because they were considered "dangerous" influences.

Dalilah and I began to secretly exchange smiles from time to time, whenever we passed by each other. Our meetings took place in the restroom area, or, when they coincided, in the exercise yard. Exercise time in the women's prison is about one hour a day, with the remaining 23 hours in your cell.

Gradually, Dalilah and I started to have more conversations. We got to know each other's cases through quick messages as we passed by each other during the exercise time.

– My name is Dalilah. I was forcibly disappeared for 70 days in the National Security Agency. I was accused of belonging to a terrorist organization.

– I am Shams, a journalist who was kidnapped with my husband and another friend from the street. I was placed in pretrial detention for 24 hours before I was accused of belonging to a terrorist organization.

Every brief interaction ended with a smile mingled with melancholy, our eyes gleaming under the bright sunlight. In those moments, we could hear each other's voice.

Dalilah would leave her cell, followed by me, under the watch of the Nabbatshiyyat, or female shift guards—the oldest female prisoners appointed by the prison management—along with three female prison guards who monitor the movements of each prisoner. We passed by a rectangular area called the kitchen, where prisoners would meet every morning. More than a hundred prisoners rush to prepare their food before the door closes at 2:00 p.m.

Three women, each from a different political current in Egypt, and each with her own political orientation and ideological affiliation, met in prison because they were accused of the same crime: belonging to a terrorist group.

- Solafa Magdy

With her two small, bright-white hands that have visible veins, and a blowzy face, Dalilah went to her bed in her cell to hold the Quran. She clutched her white glasses, to navigate through her own world. She reads the Quran and glorifies Allah, then takes one of the books that her family was allowed to bring in. She completely disconnects from her surroundings for hours and hours. She even forgets to eat or move from her bed and engage with other inmates. Her behavior provoked resentment among some inmates, thinking that she was somewhat arrogant. No one knew what was going on in her mind except me. It is a rare kind of friendship overshadowed by strangeness, honesty and pure love.

The shift guard became aware of that friendship and did not hesitate to work on destroying it. One night, she went to Dalilah's cell. Dalilah was not used to this, because the shift guards are somewhat afraid of approaching political prisoners, unless they have orders from the security officer in charge of receiving shift cell reports. She started talking to her about the economy and business, because Dalilah had worked in that field. Then they talked about me, and the shift guard told Dalilah a supposedly dangerous secret.

"Shams works with the security. She has problems, and everyone is doubtful of her. Be careful of her," the shift guard told Dalilah. The shift guard was surprised that Dalilah did not believe her and politely ended the conversation.

Our friendship was strengthened. We'd spend hours together when we were allowed to meet. We exercise and eat at the same time. We drank coffee at 9:00 a.m. every morning in the "kitchen." We'd prepare it using a tin can—like a can of beans, for example—after buying them from the prison cafeteria at double the price.

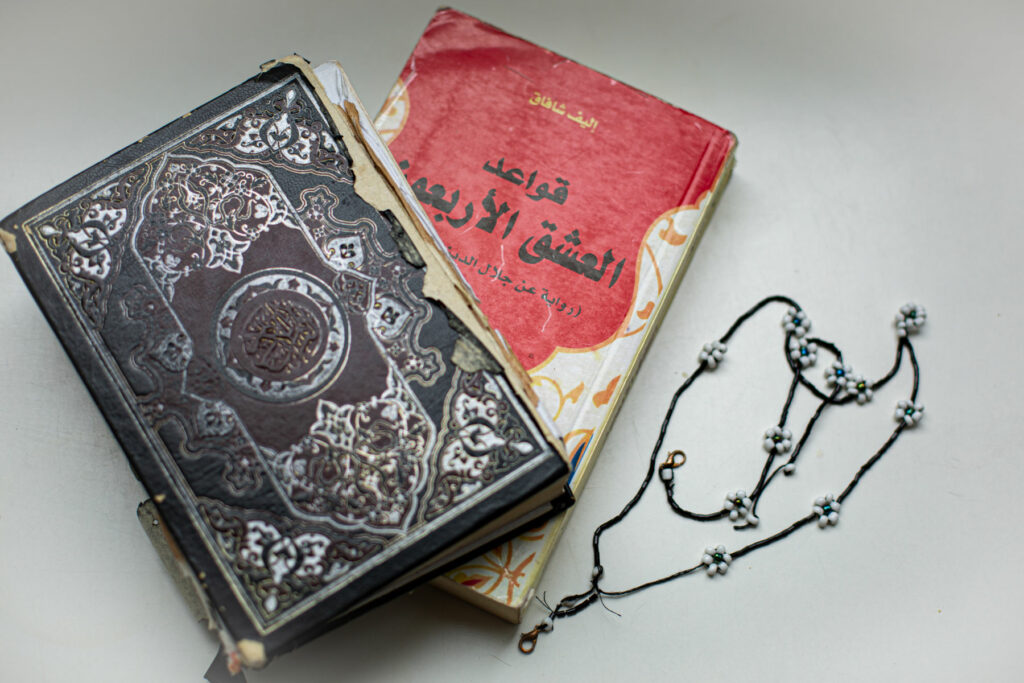

We shared thoughts and laughs. We had discussions about every book we finished reading. The closest book to our souls was The Forty Rules of Love, by Elif Shafak. We read that book many times—so many that we memorized conversations between Jalal al-Din al-Roumi and his soulmate, Shams al-Din Tabrizi. It was why Dalilah decided to call me "Shams." She found in Shams the needed friendship that she had always looked for outside the prison, as she used to tell me.

As for me, I decided to call her Dalilah, an Arabic name meaning guide, as she was a friend and a guide on those dark nights in prison. She was the guiding light in my steps, in making decisions, in perseverance, and in standing up to the abuses I faced there.

Nearly three months since our friendship began, a group of female prisoners arrived one day. They were as usual distributed among a number of prison wards. They are called the "new supply." These are the group of female prisoners whose stay in the reception cells of new arrivals has ended. Those transit cells are the worst time for the inmates before beginning their journey in the labyrinth of prison. An inmate is supposed to stay in the transit cell for about 20 days, but this group was unlucky. With more than 70 inmates, including criminal and political prisoners, they were forced to stay around 100 days in the transit cell, whose area does not exceed four-by-four meters. It has a toilet with a wooden door full of holes and no ceiling or privacy.

The inmates are not allowed to shower without the permission of the cell Nabbatshiyyat. They fell into that time gap in conjunction with the closure of the prison due to COVID-19 and the precautionary measures announced by the Egyptian government. Contrary to what is expected and logical, the authorities did not evacuate the prisons as precautionary measures to prevent prisons from becoming a hotbed of the pandemic. They decided, however, to close the prisons and prevent visits and correspondence for some political prisoners, including myself, as a humiliating measure, because I decided to express my refusal for this closure and went on hunger strike trying to pressure the official bodies to listen to those behind bars, but with no success.

It seems that destiny decided to bring me and Dalilah an unexpected gift. Our share of this new group is Safa (also a pseudonym). She is an Egyptian girl with the Nile tan, and with distinguished black eyes filled with determination and boldness. She wears a white veil, believing that her voice is not 'awra (an intimate part of the body that must be covered, according to Islam), as some believe in the Islamic current to which Safa belonged.

She instead belonged to those who consider the voice of women a revolution. This is what led her to pay the price for what she believes in. She was sentenced to a full year in prison, following a verbal argument about the political and social conditions with one of her neighbors who defended the Egyptian regime. She fell prey to the campaign of the Egyptian TV shows and newspapers that encourage citizens to report on each other. This neighbor hurried to report his veiled neighbor, Safa, to the security authorities, under the pretext that she belonged to the Muslim Brotherhood and sought to destabilize the security in the neighborhood in which she lived.

Her arrest warrant was issued. Because she is a lawyer, Safa came to know about this from a colleague. She decided to submit herself to the authorities to prevent any harm to her home and her three children, so that they do not see their mother being arrested. However, this did not help her case. Instead of suspending the sentence, the judge sentenced her to one year of imprisonment in the women's prison of al-Qanater.

One morning, the cell inmates woke up to a loud and sharp voice, an argument between Safa and the cell Nabbatshiyyat:

– I have the right to put my clothes bag in a place other than the mattress I sleep on with another inmate. I have the right to a mattress of my own. This is what the prison regulations say.

This voice caught our attention. We were impressed by the boldness of the veiled woman and insistence on her right guaranteed by the prison regulations. Dalilah and I looked at each other with a hidden nod and smile. We knew that there would be a trinity soon in this place.

In the backyard of the cell, we were sitting across from each other on a pair of stones and what was left of the wood in the exercise yard, listening to Fairuz songs in the morning, swaying to her tunes like leaves in autumn, before our tears would force us to sit on the ground, like falling leaves. There were also some prisoners in the yard who clean the area and collect trash in bags that they carry on their heads all the way to the outer door to the trash truck.

At other times, we would force our feet to run, in an attempt to overcome the stiff bones from staying for long hours in the cell that was soaked with moisture and lacked heating all the time, where the frost reached our bones and began to gnaw on them for months and months.

We kept these habits until Safa got to know us. The hour of exercise in the morning, the evening coffee, and listening to radio broadcasts of news, if we were able to pick up the BBC signal, brought us together. The news bulletin ends with Dalilah's and my last sip of coffee, before we turn the cup upside down on the blue plastic plate and read our fortunes in the coffee grinds. I preferred the blue plate, and I covered it with tissues. It made me feel optimistic and relaxed, or so I thought. Whenever our friend Safa saw us reading the cup, she would ask us not to do so in her usual friendly way. We would accept her request with a smile full of disapproval and wonder. She did not understand that we are just having fun, or maybe hoping to know the future. Would we choose this pure revolutionary side again knowing that we will end up in this dismal place that gave us the opportunity to meet?! We continue to read the coffee cup, laughing at times and crying at others, lost between hope and pain. But we were insisting on overlooking any pain in order to continue and resist.

The usual quarrel ends, and they are sitting on my bed. It was their preferred bed. They felt as if they were visiting a friend's house, even if it was an illusion, which they had created for themselves in order to survive.

My bed was always clean and fragrant, covered with a sky-blue sheet, interspersed with some light pink roses. On both its sides, I made pockets from the remaining worn-out clothes to put my personal belongings and my clothes in. On the other side, there is a rope of thin cloth extending throughout the bed, where I used to hang colorful hair ties and my little boy's drawings, and a rosary made for me by my husband, who was also in the men's prison. I always kept some sweets that were rarely allowed in during visits, for my friends. They always pretend that I surprised them with those sweets, so that we could laugh together. Sometimes, I was allowed to hang a sheer curtain on the rope, which gave us a little privacy that we've always lacked since the first moment we entered the prison. Having a little privacy there is a big thing.

The discussion begins about the latest news with an attempt to analyze it. Our thoughts converge and our convictions clash. We sit on the bed behind a locked iron door surrounded by a fence. In every meeting, Nabbatshiyyat and other inmates try to overhear what is going on between this trio despite their different political affiliations. For them, this is hard to believe. It was difficult for others to understand what was going on in the minds of the three girlfriends. A unique friendship brought us together, in a way that happens only in novels. This happened in a cell where we met because of the decision of one jailer and one accusation, without our jailer knowing that he had done us a favor. The journey of searching for each other over the past 10 years finally ended behind a locked door, guards and walls.

At first, Safa was afraid to deal directly with me, fearing that I might criticize her for her political affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood. Also, it was usual for those belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood to attack those belonging to the civil current because, from their point of view, those in the civil current overlooked the violations that occurred against the Muslim Brotherhood in some political events, especially the dispersal of the Rabia al-Adawiyya sit-in. On the other hand, those like Safa have always received criticism from those belonging to the civil current and those without any political affiliation, for wearing the niqab without even speaking to them or engaging with them.

Our fear of each other was our point of convergence and rapprochement. We had honest conversations. Safa told me that she was trying to search for other parties outside the prison to fill that missing link between the three political currents: the civil current, the centrist Islamic current and the Muslim Brotherhood. Our friendship grew solid, sincere and unique in a place and time that no human mind could have imagined. We did not expect that our friendship would irritate some of those around us, as well as the prison authorities. But the three of us did not pay attention to the attempts to discredit and separate us.

We were sharing clothes and food. We shared many dreams, hopes and pains. The three of us are mothers of children between the ages of two and 20 years old. Safa was talking about her baby. She was very concerned that her child would abandon her after she left him for one whole year. She cried and laughed at the same time. She is kind-hearted, pure, loves violently and also hates violently. Her stances are always clear and specific.

Dalilah was a good listener all the time, by virtue of her work as a successful businesswoman, who gives advice and helps her friends and everyone who turns to her. Dalilah suffers in silence and always talks to me about her concerns that her children may blame her because she may have disrupted their lives after her imprisonment. She only cries when sitting in front of me. She considered me her other half, the friend that she always looked for.

I was listening and giving advice, trying to calm my friends, especially Safa. I was trying to curb her ferociousness and revolution. I preferred not to mention my little boy's name in this dismal place. This was always my weakness. I had always been afraid of collapsing in front of those stalking me in prison. I preferred to hide the feelings of nostalgia and longing for my child deep down until I could see him again. But I used to talk a lot with Dalilah only. I found in her what I needed. Dalilah guided me to my soul, and to the peace that I have always searched for.

I found this feeling with Dalilah only, despite our radical differences in many opinions and political affiliations. However, our pure love and our agreement to love this country was sufficient and satisfactory for us to overlook those differences. Our discussions have always been objective and respectful. Certainly, there has been criticism of some of the decisions of each of our currents. In one of the discussions, I thought of documenting those defining moments in our lives as friends here. Dalilah and Safa liked the idea. They had the same desire, but without knowing that each of us would welcome it. We shared our thoughts and laughed together. Our thoughts and conversations have become similar.

Once at sunset, Dalilah saw two doves that entered the cell through the door window. She looked at them and felt they are like us. One of them flew out, followed by the other. "You see!" she said. "One of us will get out of here and the other will follow."

- Solafa Magdy

As Safa's revolutionary impulse has always been the motivation for us, she expressed her desire to start on that journey. She felt that it would change the course a little bit, and it would strengthen our relationship even more. We pledged that our friendship would continue forever. Safa talked about her feelings and thoughts toward her homeland and toward us in her own way. Safa smiled and sighed, her eyes flashed as if they were pulling something buried deep inside her soul:

– I see myself in the midst of the crowds in the Square, I smell the fragrant scent of the protesters. I was looking for the other parties because I always felt that we have something in common that must remain, and that I must fix the false image of me as someone belonging to the "Muslim Brotherhood" in the minds of those belonging to other currents, especially the civil current.

She took a sip of her cup of tea, and looked at us as if she wanted to confirm what she would say with all her senses:

– Prison has changed my view of many things. Prison imposed an inescapable reality. We are in this cell together, either we support each other and unite against the other (the jailer) or we leave ourselves to our impressions of each other that make us tools in the hands of the jailer to use us against each other. My view of other currents has changed. I tried not to wrongly interpret their opinions. I knew that some of those belonging to the civil current had a bad idea of me as a person belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood. I had to try to correct that view in the best interest of the country. We all have to exchange roles and accept all opinions. When I saw people in the revolution from the civil current and centrist Islam like you, Shams and Dalilah, and after sitting with you, my view of many things has changed. I made sure that I am not the only one loving this country. My view was that the civil current accepts those belonging to centrist Islam more than they accept me, so I didn't let you, Dalilah, be the link between me and Shams. With the passage of time and after the exchange of opinions in prison, I realize that we almost have the same ideology, but the different classifications and names outside help in creating distances between us. I think we would never understand each other with this degree of transparency and depth without being together in prison, unfortunately.

I looked at her and Dalilah, and we all smiled at the same time. Our eyes filled with tears. They were tears of regret for the time we spent on our differences, even though the protests in the Square received all of us. We were in the streets and we had every opportunity to meet and talk. However, those who dominated the scene at the time decided to cling to the disagreements, and they have lost. We all have lost. We must compensate for the past here behind bars.

At first, Dalilah preferred to be a listener, as she has always been. Safa felt that I had something to say. I asked her if there are attempts by some to separate us. Safa was reluctant to answer initially, but then she burst out laughing like a child: "Yes to be honest." Then she said:

– I faced many attempts from some people to separate us. Some said: You don't know that Shams belongs to the civil current, to those who betrayed us and sold us out, and your friendship with her will put you at risk of adding more charges to your case? I was always striving to change their misconception, and that we are now on one side, and that we must unite and put aside our differences. I tried to explain to them that the trust between me and you, Shams, and Dalilah, was built on our presence in the January Revolution. There is always a common dream that unites us—it is the revolution.

In the end, I came to the conclusion that our only solution is to be as we were before, united to understand each other and have good faith in each other. We all love this country, but in different ways. Perhaps you, Shams and Dalilah, think there might be some of those belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood who are exclusionary and accuse others of treason and do not accept the other. Yes, unfortunately. They, however, share with us the same pain as they are also detained, but they did not learn from this experience. I have the responsibility to the link between you and them.

Safa's words were like peace to me. Dalilah's thoughts were not much different from Safa's. She confirmed a point that we had discussed privately. Dalilah and I always had conversations to the tunes of Umm Kulthum every evening. We always sang some excerpts that are dear to our hearts, like, "This world is a book and you are the thought." Dalilah always sings this part with a beautiful smile of pure love and serenity of soul that I never felt before.

Dalilah had a special place in my heart. She used to give me loving words written on paper boats she made off the scraps of paper that we were able to smuggle from some prisoners for a small amount of money. She was trying to make me happy, in order to ease my tension because of everything that was going on around us. Prison did not only bring us together physically; it took us even beyond that. It brought our thoughts and souls together. We had telepathy in thoughts and in dreams as well.

She kept waking me up early in the morning for dawn prayer together. We would sit near the iron door, looking at the visible part of the sky from the door's small window. This used to provide us with some energy, even if it is imaginary, but it is one of the few things that made us stand up until I was able to sit today behind a computer screen and write these lines. Once at sunset, Dalilah saw two doves that entered the cell through the door window. Dalilah called me to tell me that she was watching them every day coming at the same time. She looked at them and felt they are like us. One of them flew out, followed by the other. "You see!" Dalilah said. "One of us will get out of here and the other will follow. We will not part outside, daughter of my soul."

Shams has flown out of the walls, and you, Dalilah, are still there alone. Shams will not shine until you are out, my dear.

Dalilah's and Safa's ideas were somewhat similar, but Dalilah and I were both subject to campaigns of distortion and intimidation. Some of those belonging to Islamic movements considered her responsible for the blood that was shed in the bloody events of the past seven years. She has always been relentlessly trying to change that view.

We lost track of time. We realized it was midnight when an angry voice shouted, "It's sleep time. Stop your talk that got you to prison." It was the voice of the Nabbatshiyyat. She spoke to us as if she were in the highest tower outside those walls. Whoever wants to pray, take a shower, or make a hot drink to warm her up a bit, she must get permission from the Nabbatshiyyat. Most of the time, the request is turned down. The Nabbatshiyyat is the ruler in prison. Dalilah, Safa and I always stood against her when she was trying to abuse any of the inmates, whether they were political prisoners or criminal ones.

The three of us had a burning desire to continue our conversation. We decided the next day to have lunch together early. We were not allowed to eat together because Dalilah's bed was not in the same cell as us. We were only separated by a piece of cloth, but that was considered a different cell under another Nabbatshiyyat. At lunch, I told them about a situation that brought joy and strength to my heart. One day, one of the criminal prisoners insulted me. This was with the approval of the cell Nabbatshiyyat. The political prisoners were angry about that, but when the guards came to end the matter by closing the cell door, many of those who were with me took a step back, fearing threats or solitary confinement. Suddenly I heard a faint voice behind me: "We are at your back. The [Muslim] Brotherhood are with you." I did not see who said that, but it gave me more power and resilience. The quarrel ended and I sat thinking about who said that. It turned out to be Safa and another inmate. They wanted to stand with me against those who insulted us.

I realized then that the mistakes of the past should not be repeated. I have to document my experience behind those doors with the people who were supportive during that difficult time. Without them, I would not have survived, I would not have been able to tell you this story.

I hear the question that some of you have. Yes, we are still friends despite the distances between me and both Safa and Dalilah. We pledged that our friendship would last forever.

But I still have a severe feeling of guilt, the survivor's guilt. I got out, but I left my loved ones, Safa and Dalilah, in that dismal place.

Will our experience help make a small difference in the way fanatics think? Will some decide to make intellectual revisions of the mistakes that led us to where we are now? Many questions in my head are looking for answers. But all the memories I lived with them will remain the underlying strength that will always push me forward, inspire me to grow, and give me power.

Editor's note: This essay is adapted from an upcoming book that will be published later in 2022.

![Security forces loyal to the interim Syrian government stand guard at a checkpoint previously held by supporters of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, in the town of Hmeimim, in the coastal province of Latakia, on March 11, 2025. Syria's new authorities announced on March 10, the end of an operation against loyalists of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, after a war monitor reported more than 1,000 civilians killed in the worst violence since his overthrow. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the overwhelming majority of the 1,068 civilians killed since March 6, were members of the Alawite minority who were executed by the security forces or allied groups. (Photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR / AFP) / “The erroneous mention[s] appearing in the metadata of this photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR has been modified in AFP systems in the following manner: [Hmeimim] instead of [Ayn Shiqaq]. Please immediately remove the erroneous mention[s] from all your online services and delete it (them) from your servers. If you have been authorized by AFP to distribute it (them) to third parties, please ensure that the same actions are carried out by them. Failure to promptly comply with these instructions will entail liability on your part for any continued or post notification usage. Therefore we thank you very much for all your attention and prompt action. We are sorry for the inconvenience this notification may cause and remain at your disposal for any further information you may require.”](https://dawnmena.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/syria-22039885951-360x180.jpg)