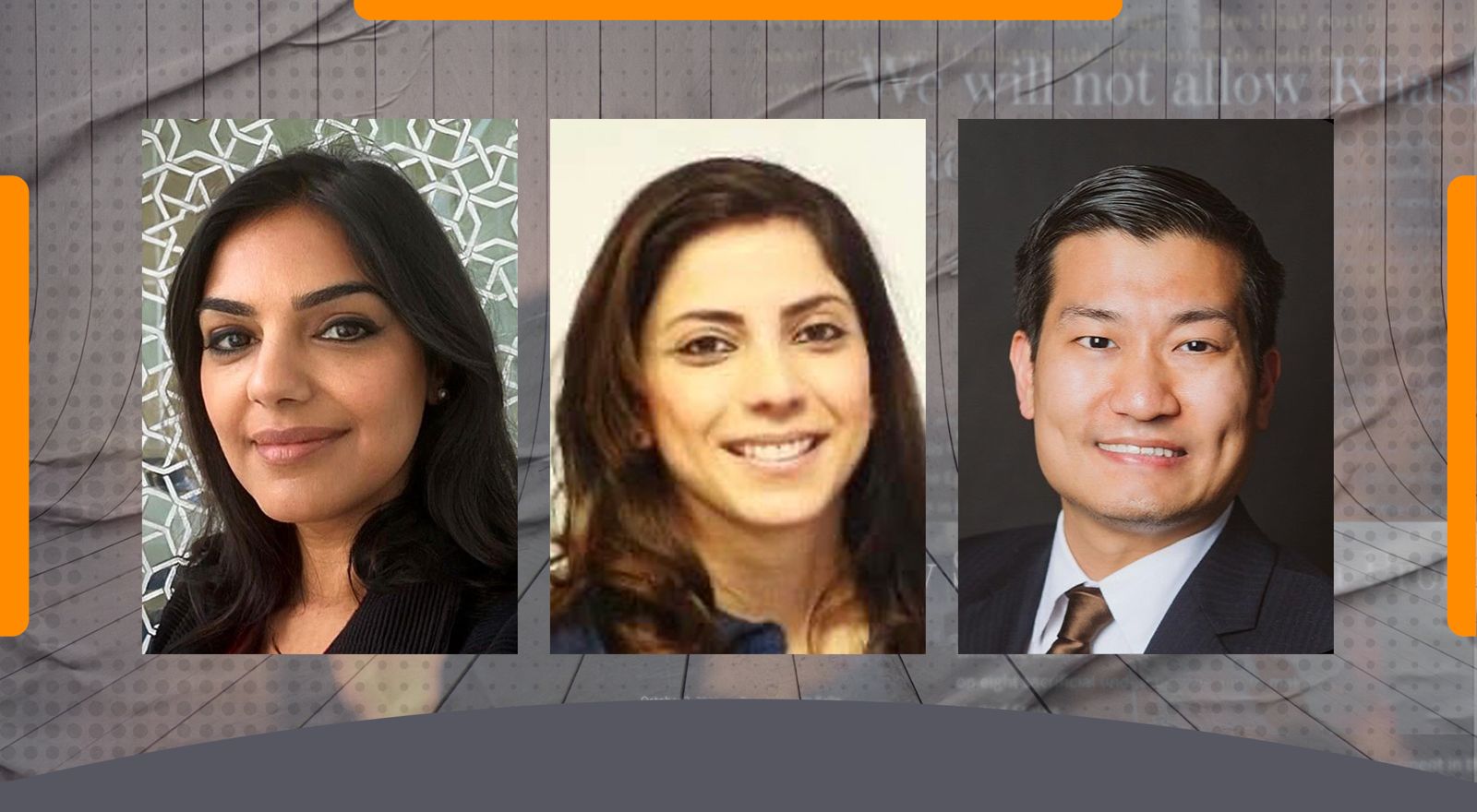

Sean Yom is an associate professor of political science at Temple University, who specializes in Middle East politics and U.S. foreign policy.

In his meeting Tuesday with President Donald Trump in the White House, Jordan's King Abdullah should have issued a desperate plea from one of America's closest Arab allies: stop blackmailing the Hashemite Kingdom. Trump's demand that Jordan accept the forcible relocation of Palestinians from Gaza—part of Trump's talk that the U.S. should "take over" the Gaza Strip, expelling its entire Palestinian population—is a catastrophe for the kingdom, and for King Abdullah. Trump has suddenly pushed U.S.-Jordanian relations to a harrowing point, undermining Jordan's most sacrosanct interests and threatening its political stability. This entire episode exposes the destructive writ of American hegemony, and Jordan's own authoritarian shortcomings.

King Abdullah has been the first Arab head of state to visit every incoming U.S. president since the Obama years. This time, after deflecting questions from reporters about whether he supported the U.S. "owning Gaza" and looking deeply uncomfortable as Trump rambled and insisted that "We will have Gaza… We're going to take it," the king might have wished he stayed in Amman.

Trump's demand that Jordan accept the forcible relocation of Palestinians from Gaza is a catastrophe for the kingdom, and for King Abdullah.

- Sean Yom

Jordan resides in a vexing neighborhood. It usually faces so many crises—economic downturns, influxes of refugees, neighboring wars, popular protests—that to frame it as perpetually "on the brink" of disaster is clichéd. What prevents disaster is American support—lots of it. Since the Cold War, the U.S. has staunchly defended Jordan's sovereignty under Hashemite rule. It has delivered over $30 billion in foreign aid since the 1950s, making it the second-largest peace-time recipient of American aid outside of Israel. Much as Jordan needs U.S. funding through cash grants and development assistance, its military has become heavily reliant on U.S. and other Western arms and training.

The kicker is that like all patron-client relationships, loyalty and cooperation must tie the interests of both sides. For the most part, Jordan's leadership has long played the dutiful role of cheerleader for American grand strategy in the Middle East. The 1994 Jordan-Israeli peace treaty reflected such realpolitik, inked under the shadow of American pressure and inducement. So, too, did Jordan's participation in the post-9/11 "war on terror" and the disastrous invasion and occupation of Iraq, with the U.S. evoking little concern with Jordan's worsening human rights abuses. When Syria's popular uprising morphed into a brutal civil war, the kingdom became host to an escalating armada of American and NATO military forces. Jordan is what political scientist Pete Moore has called "Washington's Bahrain in the Levant." The bargain seemed clear: So long as Jordan followed America's strategic lead, Washington would support its stability with billions in economic aid and security assistance, while making little fuss about authoritarian repression.

The war in Gaza upended everything. Since the Oslo Accords and its peace treaty with Israel, Jordan has adamantly advocated for a two-state solution. A majority of its own populace originates from Palestine, the product of the 1948 and 1967 Arab-Israeli wars, when nearly a million Palestinians who were driven from their homes settled on the East Bank of the Jordan River. There are around 2.3 million registered Palestinian refugees in Jordan today—the largest number of Palestinian refugees in the world—but the total number of Palestinians in the kingdom exceeds that, because not all Palestinian-Jordanians (the majority of whom are Jordanian citizens) hold refugee status. According to one recent estimate, Palestinians in Jordan could number at least 4.4 million out of Jordan's total citizen population of about 7.5 million.

Given this demographic schism, Jordanian society has struggled to build a coherent national identity. Since the 1950s, the Hashemite monarchy has managed tensions between tribal Jordanians—also known as Transjordanians, which refer to those residents who trace their lineage to this area prior to the kingdom's colonial birth in 1921 as a British Mandate—and Palestinian-Jordanians through a mix of repressive laws and patriotic charades. Yet both Transjordanians and Palestinian-Jordanians see Israeli aggression in the West Bank and Gaza as an existential threat. Their worst nightmare is the "alternative homeland" scenario, the aim of right-wing Zionists going back to the British Mandate of Palestine: Israel should annex all of historic Palestine and forcibly displace its entire Palestinian population to Jordan, which would then become the new Palestinian state. This would not only extinguish Palestinian self-determination and constitute ethnic cleansing, but would also destabilize an already poor, strained Arab autocracy.

This entire episode exposes the destructive writ of American hegemony, and Jordan's own authoritarian shortcomings.

- Sean Yom

Jordan's leadership and public stood united in denouncing Israel's war of collective punishment in Gaza after the Hamas-led attack into southern Israel on October 7, 2023. Yet encaged by its geopolitical commitments to heed the American line under President Joe Biden, who had few qualms underwriting Israel's war machine, the Hashemite regime found itself trapped. Under American pressure, it could not end the peace treaty with Israel, as its citizens demanded. Its pleas to Washington to moderate Israel's assaults fell on deaf ears. Instead, nervous about domestic instability, Jordanian authorities cracked down on anti-Israel demonstrators and activists. Jordanians interpreted this as their government effectively policing the kingdom on behalf of the Washington-Jerusalem axis, which needed Jordan to remain what it has always been: a compliant authoritarian partner buffering Israel's eastern flank. That Jordanian forces twice last year helped shoot down Iranian drones and missiles targeting Israel bolstered this feeling. Not even the sudden collapse of President Bashar al-Assad's regime in Syria in December eclipsed this simmering outrage.

Then came the return of Trump. In Trump's first few weeks back in the White House, his administration shocked royal circles in Amman with three moves. First, it froze nearly all U.S. foreign aid, with the exception of aid to Egypt and Israel, for 90 days. While U.S. emissaries assured Jordan its aid would be restored, that Egypt but not the Hashemite Kingdom was given an initial exemption was taken as an insult. Second, the Trump administration began unilaterally dismantling USAID. More than most countries, USAID is deeply imbricated into the institutional fabric of Jordanian society, almost like a parallel state, supporting everything from refugee assistance and infrastructure to education and public health. Tens of thousands of Jordanians have reportedly lost their jobs due to USAID funding on their development projects abruptly vanishing. Jordanian officials now must scramble to replace the lost capacity that USAID used to provide, if they can even find it.

Third was Trump's Gaza scenario, announcing American plans to "take over" the Gaza Strip and redevelop it along Trumpian lines into a new "Riviera of the Middle East." After Trump doubled down on his destructive plan—if it can even be called that—he publicly ratcheted up the pressure on both Egypt and Jordan to take Gaza's Palestinian population, who he also made clear would have no right of return to a rebuilt Gaza Strip. Given that the U.S. now holds Jordan's military and economic purse strings, Trump's demands amount to blackmail. Jordanian officials are beyond flummoxed. Even ignoring the baffling idea that the U.S. could legally "own" this Palestinian territory, Trump is openly advocating for the expulsion of more than two million Palestinians from Gaza, not to mention sowing economic and social turmoil in Jordan. This is Jordan's "red line." Jordanian officials have frantically pleaded with their American contacts, while publicly threatening war with Israel should the plan go into effect.

King Abdullah's meeting with Trump conveyed the same sentiment: Any pursuit of this agenda will destroy Jordan—and the U.S. needs a pro-Western Arab ally like Jordan to help it wage more disastrous wars and policies across the Middle East. At this point, the prospects for Trump's Gaza scenario appear indeterminate, clouding U.S.-Jordanian relations. The White House meeting did not resolve bitter disagreement over the issue, ending only with the king's promise that Jordanian hospitals would admit 2,000 sick Palestinian children from Gaza. That pledge has temporarily lifted the pressure on Jordan, shifting the focus to two other Arab countries: Egypt, the other putative recipient of Palestinian refugees according to Trump, and Saudi Arabia, which as the wealthiest Arab state could swing the debate in either direction. So far, both have rejected Trump's proposal.

However things play out in Gaza, this tense episode illustrates a useful lesson in unintended consequences. Autocratic rule in Jordan was built on generations of generous U.S. support that gave its monarchy vast autonomy to govern however it wanted. It is difficult to imagine how the kingdom would fare without American dollars and arms, because it has seldom had to do so. If the U.S. exits this patron-client relationship now—for instance, by threatening to abandon Jordan entirely should it refuse Trump's ridiculous idea for forcibly relocating Palestinians from Gaza—the country has no back-up plan. The European Union has agreed to provide more economic assistance, but it cannot replace Washington's hefty diplomatic, financial and military footprint. This could spark more domestic unrest and democratic mobilization in Jordan, which is precisely what Jordanian officials desperately want to avoid. Perhaps most of all, they fear a replay of Black September, in 1970, when Palestinian militants almost toppled the regime of Abdullah's father, King Hussein. Such is the peril of making illiberal bargains with a fickle hegemon.