Frederick Deknatel is the Executive Editor of Democracy in Exile, the DAWN journal.

عربي

Italian cartoonist and artist Gianluca Costantini draws everyone and everything: political comics, graphic journalism, even sports illustrations. But it is his work highlighting human rights violations around the world, in particular drawing attention to imprisoned activists and journalists, that won him international recognition, including Amnesty International's Art and Human Rights Award in 2019.

A classically trained artist from northern Italy—he graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Ravenna—Costantini got into political cartooning slowly at first some two decades ago, starting with a trip to Sarajevo. Now, he collaborates with international NGOs and human rights organizations on a range of projects—highlighting the plight of jailed journalists in Eritrea, for example, and detainees allegedly tortured in Turkey. He also works with other artists, like dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei.

Costantini's cartoons appear in a range of international publications and on his popular Twitter account. Some even hang on the sides of buildings, like his installation last year in Bologna's central square of a huge drawing of Patrick Zaki, a young Egyptian academic and graduate student at the University of Bologna who has been detained by the Egyptian government, and reportedly subjected to torture, ever since he returned to Cairo in February 2020. Costantini also installed dozens of cutout drawings of Zaki in the monumental reading room of the Bologna University Library.

Costantini has been targeted by governments for his work—most of all, the Turkish government, which accused him of supporting "terrorism" in the aftermath of the failed coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2016. Costantini's website and Twitter account were blocked in Turkey, along with 37 other Twitter and YouTube accounts deemed by Turkish authorities to be "praising terrorism, encouraging violence and crime, [and] menacing public order and national security." Costantini had simply drawn cartoons of Erdogan, among others. His cartoons are still censored in Turkey today.

In an interview with Democracy in Exile conducted over email, Costantini discusses how his art becomes activism, what responsibility an artist has to respond to politics, and "speaking for those who can no longer speak."

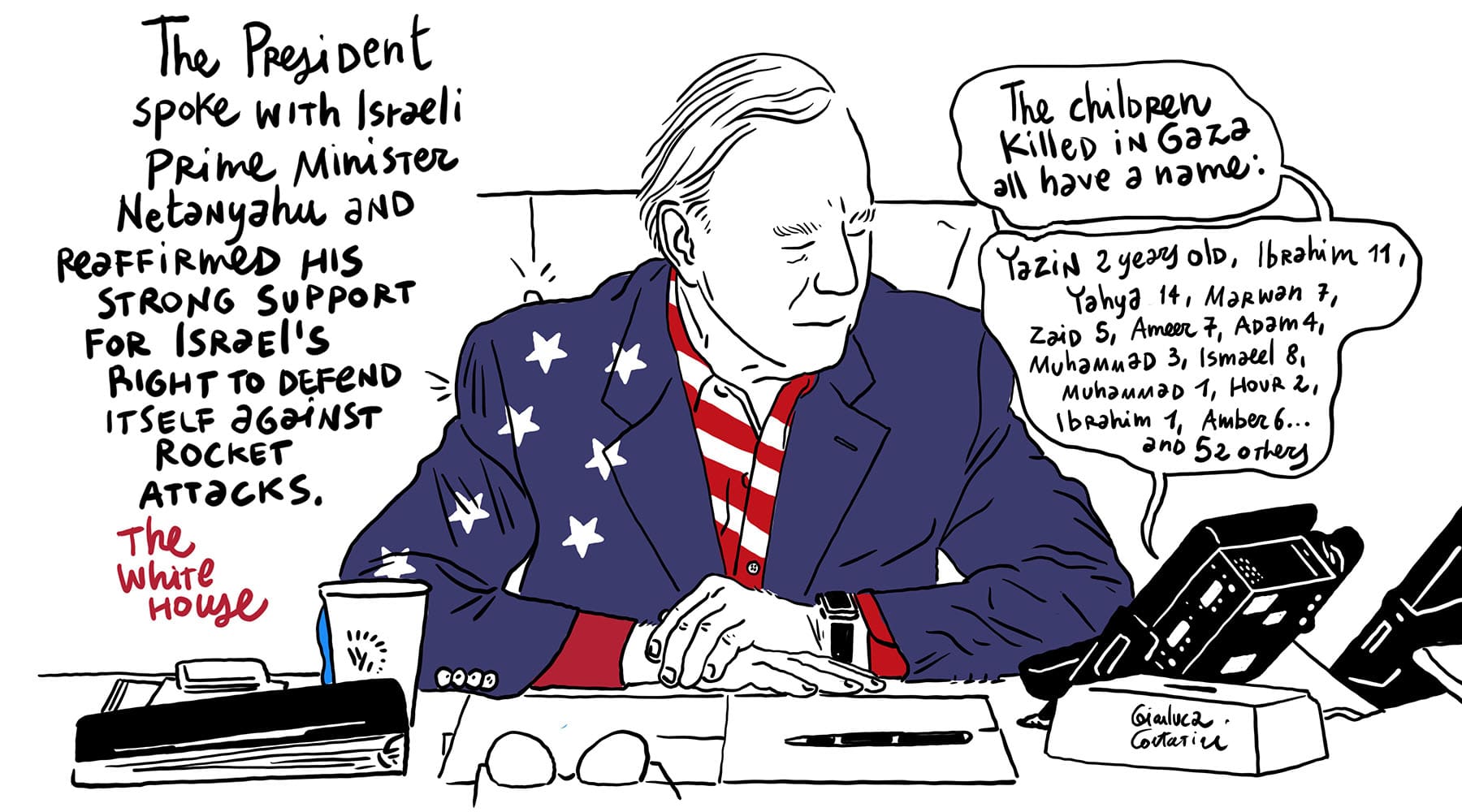

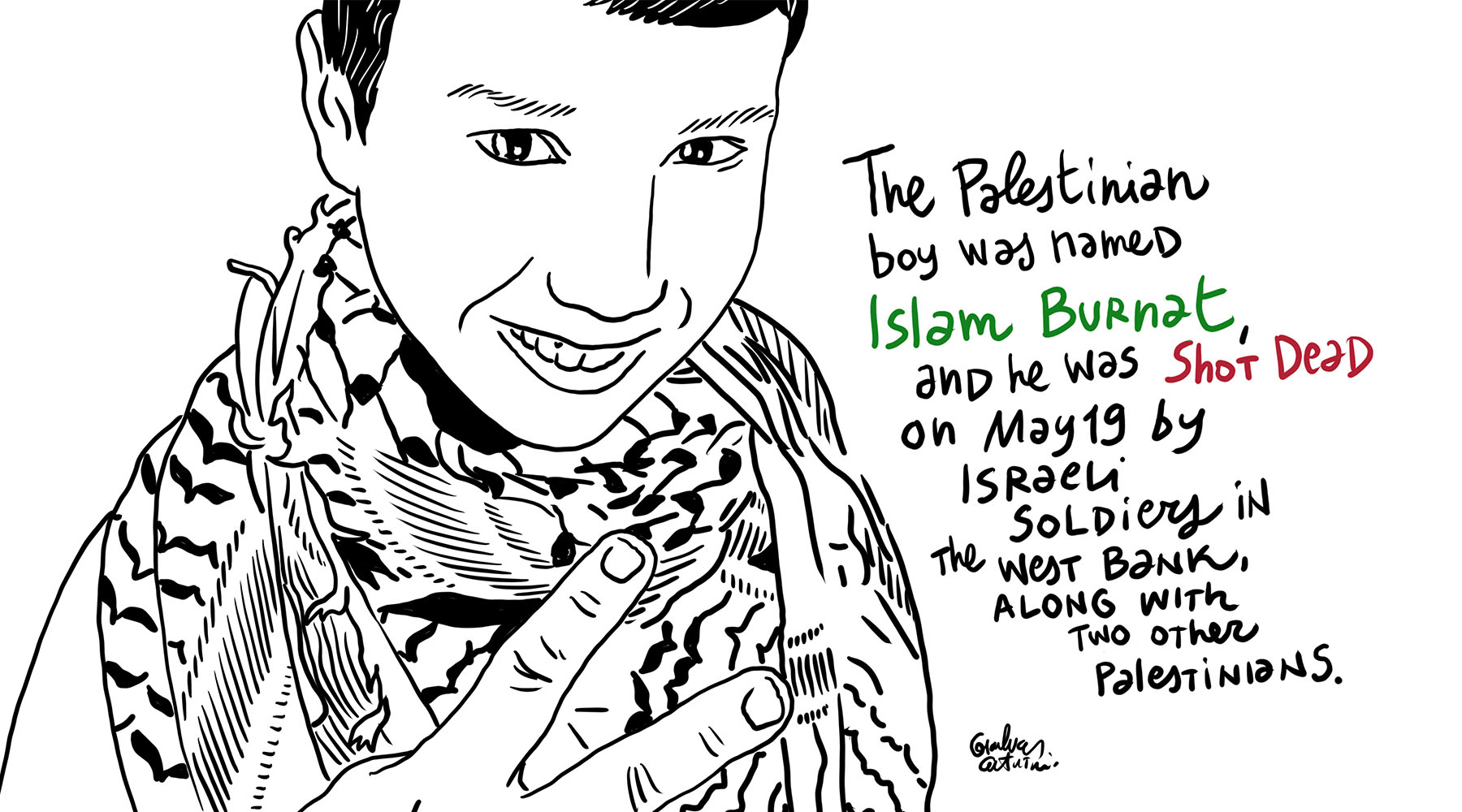

All three accompanying cartoons were drawn by Costantini this week for Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN), before Israel and Hamas reached a cease-fire agreement that took effect early Friday.

DAWN: Do you consider yourself an artist first, or an activist, or both?

I see myself first and foremost as an independent artist, who decides independently how to move and how to show myself. This self-determination of mine is in itself a political act. Little by little, I have also become an activist, as everything I draw becomes part of reality and the struggle to change it.

Art always represents reality, even when the painting is abstract. Everything comes from reality. It is vital for me to have art become embedded into reality. When I make a drawing, and then I see a picture of a person holding it and that drawing is about them—well, it means that I have achieved my goal. Seeing my drawings at demonstrations, or used by activists all over the world, makes my art right. This transcends the field of art and enters into the everyday nature of people. It is a kind of art that makes them think and act. Mine is a political art, an unfashionable, legally uncomfortable art. Art for me is uncomfortable knowledge.

DAWN: What initially drew you to making political cartoons? And when did you first start drawing cartoons about the Middle East?

In the early 2000s, I went to Sarajevo. It was the first time I went abroad. The war had just ended; everything was destroyed. The United Nations blue helmets were guarding the city. A map was distributed with the areas to avoid; they were full of anti-personnel mines. I had already been drawing and publishing for about eight years, but I was doing something else. Something from that trip stayed with me, something which was asking me questions.

I got to know authors in person who were trying to tell the world another perspective: Joe Sacco, Aleksandar Zograf, Marjane Satrapi. They triggered something in me, and the casual reading of Ernst Friedrich's book, War Against War!, gave me the idea. I started making drawings with a few words describing a situation: a journalist killed in the Philippines, a television station closed down by the Iranian government, some events of repression in Palestine, an American football champion killed in Afghanistan. I was attracted to the Middle East, almost with an orientalist, yet political, attraction. Moreover, the drawings of that period were very calligraphic, combining the sign of writing with the stroke of drawing. I have been immersed in them ever since.

DAWN: You told an interviewer last year, "Art is a tool that prevents me from looking the other way." Do you think art can prevent other people from looking the other way—from ignoring things like human rights? Do you hope your cartoons have that effect?

Initially, it helped me open my eyes. Investigating reality through drawing, I discovered and became aware of the world and its problems. I slowly entered into it. Art can be many things. What I really want to do is to make art that influences the system, that tries to change it or question it—art that interacts with the community, art that shares and does not impose. If the artist's work is independent and open to others, people will start to look at the world through the artist's eyes. In recent years, I mainly focused on human rights, and I hope that people who follow my images will start to get interested in the issues I deal with.

DAWN: How do you think an artist should respond to the kinds of troubling political trends we've seen in the past few years—with far-right politics and ideologies on the rise in Europe and the United States, for example, and retrenched authoritarianism in the Middle East?

An artist must respond with what he can do: impose a new imagination, a new way of seeing and acting. As far as my personal experience is concerned, drawing is very powerful, hitting people who look at it like an arrow. Drawing is very different from taking a picture. With a drawing, you can describe reality but, even if you are as faithful as possible, it will be different. Even if you trace a photo, the result will be different from what the photographer wanted to say. Drawing is very subjective—it's about the artist's way of seeing; it's about his or her memory. When you draw a portrait of a person, you look at them and then you look down at the paper. What you draw is already a memory.

The political situation today is serious—extreme right-wing ideologies are growing even here in Italy, even though we have a past that reminds us of it. Still, I do think that as artists we can play our part in giving a different interpretation of the society we live in.

DAWN: Turkey has tried to silence and censor you, with Erdogan's government banning your cartoons in Turkey and accusing you of terrorism. What effect has that had on your work? How did you respond to that, and how should other artists respond when they are targeted by governments?

I was accused of terrorism after the failed coup in 2016. If it was done to shut me up, it had the complete opposite effect, as I increased my work on Turkey, one of my favorite countries. I also suffered censorship and an infamous accusation of "anti-Semitism" by [Republican operative] Arthur Schwartz, a partner of Steve Bannon, for which I lost the job I was doing for CNN in 2018.

They try to shut you up with censorship. Fortunately, I was censored by a government that is not my own, so I can keep speaking for those who can no longer speak, like artists from Turkey, Egypt and many other countries.

![]()

Photo credit: Italian artist Gianluca Costantini stands with the drawings he made of Patrick Zaki, an Egyptian graduate student at the University of Bologna and researcher who is still being detained in Egypt, in the Aula Magna or reading room of the University Library of Bologna, July 16, 2020. (Photo by Michele Lapini/Getty Images)