U.S. Should End Military Support to Egyptian Government Given Systemic and Widespread Human Rights Abuses

(Washington D.C., April 14, 2022) – The forced disappearance and unexplained death of Ayman Hadhoud shows the near complete lack of accountability for Egyptian police and security officials, even when their actions kill Egyptians, said Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN).

The U.S. government, Egypt's primary military and political backer, should end its military support to Egypt given the government's widespread and systematic violations of its human rights obligations to its citizens.

"The deeply unsettling forced disappearance and unexplained death of Ayman Hadhoud shows just how terrifying life is for many Egyptians and just how little Sisi's government cares about the lives of the Egyptian people," said John Hursh, Program Director of DAWN. "Until the perpetrators for these crimes face accountability, Egyptians will continue to live in fear that they or a friend or loved one could be next."

Egyptian officials forcibly disappeared Ayman Hadhoud without explanation on February 5, earlier this year. Hadhoud died in a state-operated mental health hospital in east Cairo near Nasr City on March 5, but government officials did not notify Hadhoud's family of Ayman's death until April 9. DAWN communicated with a family friend of Hadhoud to gather and verify information about his detention and death in Egyptian state custody. Although Hadhoud's family made numerous attempts to verify Ayman's whereabouts and to visit him, they did not learn that he had died more than a month ago until they went to recover his body from the hospital on Saturday, April 9. They had not seen nor heard from Hadhoud since his disappearance.

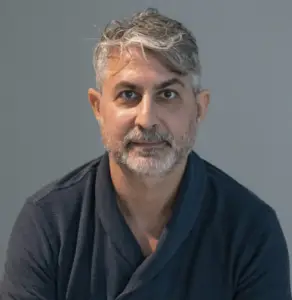

Ayman Hadhoud was a respected economic researcher and a graduate of the American University of Cairo. He worked as a financial consultant for the university and for the UN Development Program, where he helped small and medium businesses resist corruption. Although he was a founding member of the Reform and Development Party, he was not politically active, and it remains unclear why Egyptian officials targeted and disappeared him, and why he died in state custody.

"The unexplained disappearance and senseless killing of Ayman Hadhoud demonstrates that no one is safe in Sisi's Egypt," said Muhammad Kamal, Egypt Researcher at DAWN. "Hadhoud was a respected economic researcher. He was not politically active and he had no ties to political organizations critical of the government, which Sisi often uses as a pretext for arrest and abuse."

After his disappearance on February 5, Hadhoud's family made multiple inquiries into his whereabouts, but Egyptian police denied arresting or detaining him. On February 8, an unidentified police officer told the family that State Security Agency (SSA) officials were holding Ayman at a police station in Amiriya, the Cairo suburb where he lived. Hadhoud's family members visited the police station, but government officials would not confirm Hadhoud's arrest and denied that they had detained him.

About a week after his disappearance, Hadhoud's family learned that government officials had transferred Ayman to Abbasiya Mental Health Hospital for a 45-day observation supposedly due to schizophrenia. There are no records that Hadhoud suffered from this disease, and Hadhoud's brother Omar and family strongly denied that he was affected by this disease or that he had mental health problems.

According to a family friend, hospital officials confirmed that Hadhoud was in the hospital, but they would not allow the family to visit him until the Public Prosecutor provided authorization, as government officials placed him in a special section of the facility overseen by the Ministry of Interior. This section requires special approval for family visits, but the prosecutor refused this request because there was no record of Hadhoud's arrest or any mention of him in ongoing criminal cases. Of course, since security officials forcibly disappeared Hadhoud in violation of his due process rights and without arresting him, there was no record of his arrest.

As reported by Madr Masr and confirmed by DAWN, the family then approached Anwar Sadat, co-founder of the Reform and Development Party and a member of the National Council for Human Rights. Sadat filed a report concerning Hadhoud's disappearance with the Public Prosecutor, Minister of the Interior, and Moushira Khattab, Chair of the National Council for Human Rights. He reportedly also met with the Public Prosecutor about the case on April 8. Despite these efforts, the government did not provide Sadat or Hadhoud's family any information regarding Hadhoud.

Following the 45-day observation period, Ayman's brother Omar said that the family returned to the National Security Services in March only to learn that prosecutors had brought charges against Hadhoud in the Zainhum Prosecution Complex. Prosecutors again would not confirm this information, nor discuss Hadhoud's case.

During the last week of March, Abbasiya Hospital officials informed Hadhoud's family that Hadhoud had died. On Saturday, April 9, Egyptian officials called the family from Nasr City Police Station Two and told them that they could pick up Hadhoud's body from the hospital. The same day, Hadhoud's family members went to the hospital to identify the body, when hospital officials then told him that Ayman had died more than a month ago, on March 5. The Washington Post later reported that a death certificate released on April 11 provided the same date.

The Egyptian government has since provided multiple conflicting accounts of Hadhoud's arrest and detainment, underscoring the impunity with which Egypt's security, police, and prosecutors act. The Ministry of the Interior stated that officials sent Hadhoud to Abbasiya Hospital in February after he tried to break into an apartment in the Zamalek district in central Cairo and for exhibiting "irresponsible behavior." In contrast, Hadhoud's hospital records reportedly show that government officials admitted him after he allegedly attempted to steal a car in Senbellawein in Daqahlia, outside Cairo. Prosecutors, after first denying arresting Hadhoud or having any information about him for weeks, then repeated this explanation when they spoke with the family at Nasr City Police Station Two on April 9. The prosecutors did not explain why Hadhoud was supposedly in Senbellawein, which is more than 100 kilometers from where he lived.

"That the Public Prosecutor would suddenly repeat a bizarre and nonsensical story supposedly within Ayman's hospital records to justify his arrest and disappearance after months of denying that they had arrested or detained him helps explain why the Prosecutor's Office lacks any credibility in Egypt," said Hursh. "Neither explanation that the government gave for Ayman's disappearance and detainment are believable, especially after Egyptian officials denied for months that they had any knowledge of Hadhoud's location or condition."

On April 11, the National Council on Human Rights issued a statement noting its concern over the "alleged forced disappearance of the deceased," and that it awaited the results of the Public Prosecution's investigation, including an autopsy, regarding the cause of Hadhoud's death and whether he was tortured while in state custody. Hadhoud's family members stated that Hadhoud's body showed signs of torture and that they took pictures to document this abuse, but hospital staff threatened not to release Hadhoud's body for burial unless the family deleted these photos. The family complied and buried Ayman later that evening.

The same day, the Public Prosecutor's Office issued a statement concerning Hadhoud's death on their official Facebook page. This statement repeated the account of the Ministry of the Interior—not the explanation that prosecutors insisted on only two days earlier when they spoke to the family—of Hadhoud trying to enter an apartment in the Zamalek neighborhood. However, the statement gave February 6 as the date of arrest, not February 5. It also claimed that it was a guard and not a doorman, as stated earlier, who called the police to report the incident. The statement claimed that Hadhoud was "incomprehensible" on the day of his arrest, and as a result, the Prosecutor sought a court order to detain Hadhoud in a government hospital to assess his mental state. The Public Prosecutor claims that the order was deposited in its office and that it gave psychiatric officials at Abbasiya Hospital authority to prepare a report on Hadhoud's mental condition and the extent of his responsibility for his actions at the alleged incident in Zamalek.

The statement went on to claim that the Public Prosecutor's Office was notified of Hadhoud's death on March 5 and that Hadhoud died in Abbasiya Hospital due to a severe drop in circulation that stopped his heart. According to the statement, Hadhoud's body was free of any injuries and a health inspector confirmed that there was no criminal suspicion over his death, and two of Hadhoud's brothers, Adel and Abu Bakr—both mentioned now for the first time—testified that they did not suspect criminal action in his death. The statement claimed that Adel and Abu Bakr also said that Hadhoud had exhibited similar actions to those in the alleged incident in Zamalek and reiterated the government's claim that Hadhoud suffered from schizophrenia.

"The prosecutor's report contradicts its own account of Hadhoud's death that it made to his family only two days before, while also contradicting the family's statements on Ayman's mental health and the injuries that they saw on his body at the hospital on April 9," said Kamal. "These major discrepancies and very convenient facts make it extremely difficult to believe this statement or trust this account of events."

Arbitrary arrests and forced disappearances are common in Egypt, and state-sponsored torture is so widespread and systematic that it may amount to a crime against humanity. There are at least 60,000 political prisoners within Egypt. As reported by the U.S. State Department in its human rights country report on Egypt published on April 12, Egyptian prison conditions are often "harsh or life threatening," and there are credible reports of security forces torturing people to death in Egyptian prisons and detainee facilities. Medical negligence and the deliberate denial of health care to prisoners is common. Unsurprisingly, many prisoners and detainees have died in Egyptian prisons during President Sisi's rule. The true number of deaths is unknown due to the government's misinformation and lack of transparency, but the Committee for Justice documented 958 detainee deaths, including 9 minors, between June 30, 2013 and December 1, 2019, alone. Several prisoners have already died in Egyptian prisons this year.

Despite these well documented abuses, the U.S. government typically supplies $1.3 billion in military aid annually to Egypt, aid that flows to Sisi's military supporters and security officials, enabling Sisi and contributing to these abuses. Last year, the State Department withheld $130 million of this amount, overriding Congressional efforts to withhold $300 million until the Egyptian government completed a handful of basic steps to demonstrate at least minimal progress on human rights reform. Only a few days before the decision to withhold this minor amount of aid, the U.S. government approved a massive $2.5 billion arms deal with Egypt despite obvious human rights concerns.