Omid Memarian, a journalist, analyst and recipient of Human Rights Watch's Human Rights Defender Award, is the Director of Communications at DAWN.

From Nicaragua to Chad, Reed Brody has spent his career trying to hold dictators and abusive regimes accountable for their human rights violations. His legal advocacy for victims of atrocities earned him the nickname the "Dictator Hunter"—a moniker he eschews, since he believes the real focus should be on the victims. "It's really about helping victims themselves become 'Dictator Hunters,' so that we have a whole army of victims as advocates and even investigators in their cause," he says in an interview with Democracy in Exile.

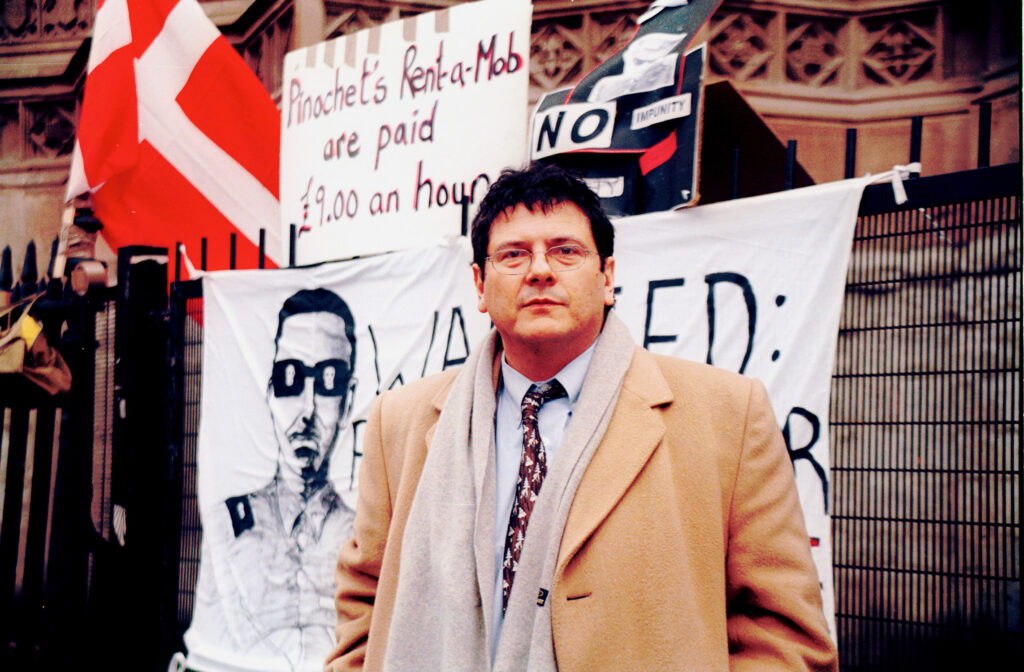

As a human rights lawyer and investigator, Brody worked on the landmark case against Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet—who was arrested in London on a warrant from a Spanish judge in 1998—and the attempt to bring dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier to trial in Haiti. In 2016, following the precedent of Pinochet's arrest, Hissène Habré, the former dictator of Chad, was convicted of crimes against humanity, torture and sex crimes by a special court in Senegal; Brody played a key role in pursuing that case. As he told reporters after Habré's conviction was announced, "This is a testimony to the perseverance of a band of victims, activists and supporters who made this trial happen. This trial was the result of the sweat and determination of the survivors."

He is now working in Gambia with the victims and survivors of torture and other atrocities committed under former dictator Yahya Jammeh, whose repressive, 22-year rule ended when he lost the 2016 presidential election and later fled into exile in neighboring Equatorial Guinea.

Brody spent much of his career, from 1998 to 2016 and again from 2017 to earlier this year, as counsel at Human Rights Watch. But he started his legal career as the New York State assistant attorney general from 1980 to 1984, until leaving to investigate abuses by the U.S.-funded "Contras" in Nicaragua.

His work in Nicaragua helped lead to hearings in Congress about U.S. support for the right-wing Contras, and was later introduced into evidence in the case brought against the United States by Nicaragua at the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which was decided in 1986. At Human Rights Watch, he wrote four reports on U.S. treatment of Muslim prisoners in the "war on terror," laying out the case for holding President George W. Bush and members of his administration accountable for torture.

Brody has also worked for the International Commission of Jurists in Geneva; the Washington-based NGO Global Rights; and on several United Nations missions and investigations into human rights violations and atrocities, including in El Salvador, Guatemala and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In his interview with Democracy in Exile, he discusses the importance of documentation in bringing dictators and tyrants to justice, and how knowing the "names, faces and stories" of their victims can make all the difference. He also reflects on "the double standard in which the powerful, and those protected by the powerful, seem to be out of the reach of international justice," including the United States and its allies.

The following transcript has been edited lightly for clarity and length.

As someone who has been called the "Dictator Hunter," can you explain your work and the process of getting justice to victims of atrocities and human rights activists?

It's great fun to be called a "Dictator Hunter," though it doesn't reflect the constructive and serious work I try to do alongside atrocity victims and activists to help them develop the legal and political conditions to get justice for themselves. That involves strategizing, seizing on the legal and political avenues, training, fundraising, building the evidentiary case, gathering support from allies, and persuading reluctant officials that it is not in their interest to stand in the way of the victims. It's really about helping victims themselves become "Dictator Hunters," so that we have a whole army of victims as advocates and even investigators in their cause. It's about victims telling their stories in a compelling way so that the public and policymakers sympathize with their quest. No one is going to be moved to prosecute a tyrant or a torturer because of what Reed Brody from New York says, but because his victims demonstrate that they deserve justice for what was done to them or their families. In The Gambia, where I work now with the victims of the exiled former ruler Yahya Jammeh, the victims and activists wear a t-shirt that reads "I am a Dictator Hunter"—because they are the "Dictator Hunters."

And it usually takes tenacity and persistence. We worked on the Hissène Habré case for 16 years before he came to trial. But the great thing about victims is that they never give up fighting.

You've been in this work for decades. Do you see any meaningful changes in the international legal system and public awareness in facilitating and helping this process for justice and accountability?

Absolutely. The sea change came in 1998, and it was part of the general tide in favor of human rights that followed the end of the Cold War. In July 1998, the International Criminal Court was created in Rome, followed that October by the arrest in London of the former dictator of Chile, Augusto Pinochet, on a warrant from a Spanish judge. When the British House of Lords ruled that Pinochet was not immune from arrest despite his status as a former head of state, I said that it was a "wake-up call" to tyrants. But the more important and more lasting effect of the case was to give hope to other victims and activists. All of a sudden, we had an instrument to bring to book people who seemed out of the reach of justice. The Pinochet case inspired victims of abuse in country after country, particularly in Latin America, to challenge the transitional arrangements of the 1980s and 1990s, which allowed the perpetrators of atrocities to go unpunished and, often, to remain in power. Justice is now always on the table after every mass atrocity, even if impunity is still the norm.

There has been a backlash, of course, since Sept. 11, 2001, and even more with the rise of authoritarian and populist governments around the word. We live in what David Miliband has correctly called "the age of impunity"—when the crown prince of Saudi Arabia pays almost no price for the brazen and gruesome murder of Jamal Khashoggi; when China can put upwards of a million people in harsh "reeducation camps" in Xinjiang. The list goes on. But at the same time, people are more connected, more aware and more organized, than at any time in human history. Broad social movements are claiming rights for people. And ultimately that is how all real and lasting change comes about.

What's your advice to victims and families of serious human rights violations in pursuing accountability of violators around the world? Where should they start?

They should start by documenting as much as they can about the crimes, the individuals directly responsible, and the chain of command. One of my partners on the Pinochet case in London was a wonderful Chilean lawyer named Roberto Garretón. Twenty-five years earlier, as the Catholic Church's legal director in Chile, Roberto had intrepidly recorded Pinochet's crimes as they were being committed. He filed over a thousand petitions of habeas corpus on behalf of the detained and "disappeared," and not a single one was granted. "I used to ask myself why I was even doing this," he told me. "But now with Pinochet in the dock, I realize it was all worth it."

Today, we see courageous victims and activists creating that record even in closed societies like Eritrea and Syria—gathering documents, taking photographs. That's also the animating idea behind the new generation of U.N.-backed "investigative mechanisms" for Myanmar, for Syria, and for Da'esh [The Islamic State, or ISIS], which are responsible for gathering evidence of serious crimes for future prosecutions. One day, this evidence will be used.

The other thing I have found important is to personalize the crimes by telling the stories of individual victims. People like Souleymane Guengueng of Chad who from the depth of his dungeon took an oath that if he ever got out, he would fight for justice. And like Martin Kyere of Ghana, the sole survivor of the massacre in The Gambia of 59 African migrants. Martin jumped from a truck before the others were gunned down, fled bullets into the woods, and, after returning home to Ghana, made it his life mission to find the families of his fallen comrades and rally them for justice. Stalin reputedly said that "A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic." The photos of the drowned Kurdish boy on the beach were more powerful than hundreds of refugees on a boat.

Going back to my Roberto Garretón story, by the time Pinochet was arrested in London, Roberto was the U.N. rapporteur on human rights in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In Chile, he told me, there were exactly 3,065 dead and disappeared, and "we have the names and stories of every single one." In the DRC, by contrast, in the bloody aftermath of the 1994 Rwanda genocide, he said, "I can't tell you if there were 1 million people killed, 2 million or 3 million." One important reason it was possible to arrest Pinochet—whereas the longtime Congolese dictator Mobutu Sese Seko never came close to answering for his crimes—was that Pinochet's victims had names, faces and stories.

Your work has been mainly focused on Africa, from Gambia to Chad. How has the international legal system changed in bringing rights violators to justice, and from the societal side too?

I got involved very late in Africa justice work. After the Pinochet ruling, a Chadian activist, Delphine Djiraibe, came to me and said, "Hissène Habré is our Pinochet, we want to do what Pinochet's victims did." And after Habré's conviction, we were approached by the Gambian victims of Yahya Jammeh, who said, "We want to do that too." We brought the leading Chadian victims to Gambia to meet the association of Jammeh's victims, who were inspired by how the Chadians had overcome so many obstacles. A great thing about these victim-driven cases is that they are replicable. When the Chadian victims watched videos of the victim-driven trials of ex-dictator Ríos Montt in Guatemala and paramilitary leaders in Haiti, they saw in those images exactly what they were trying to do.

There is a belief now among African activists that accountability is possible. Investigations, documentation and prosecution are taking place across the continent, both by NGOs and by governments. When we began working in Chad 25 years ago, some victims thought we were crazy. "Since when has justice come all the way to Chad?" my friend Souleymane was asked. Now people ask, "Show us how we can do it."

How is it possible for people to hold U.S. allies accountable in international courts like the ICC, considering the type of relationship the U.S. has had with the court in the past?

There's a double standard in which the powerful, and those protected by the powerful, seem to be out of the reach of international justice. This inequity is entrenched by a Security Council veto, but it's not just at the ICC that we see this imbalance. Ninety percent of what is happening in international justice is happening away from The Hague, in national courts, and the double standards are also at work there. Belgium and Spain had the broadest universal jurisdiction laws in the world to prosecute foreign atrocities.

But after a case was filed in Belgium against U.S. officials over the bombing of a civilian air raid shelter in Baghdad in the first Gulf War, then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld warned that NATO headquarters could be moved out of the country if the law was not repealed, which it quickly was.

Spain's law was used in the Pinochet case in trials of Argentine and Salvadorean officials, but when cases where filed against officials from the U.S., China and Israel, that law was cut back too. As much as we seek to protect the independence of judges and prosecutors, it's wishful thinking that the institutions of international justice can operate outside global power relations.

But as activists, we can work to change those power relations, to raise the cost of hypocrisy and inaction, to call out the double standards. As my late friend and mentor Michael Ratner said, we shouldn't refrain from pursuing cases just because they appear to be long shots, and we need to combine legal work with political advocacy and to use litigation to publicize a radical critique of U.S. policy and to promote progressive transformation.

I was involved with Michael and Wolfgang Kaleck of the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights in criminal cases filed in France, Germany, and Spain to hold Rumsfeld and other U.S. officials accountable for crimes against detainees in the "war on terror." None of these countries was willing to stand up to the United States. The cases were dismissed, but we used them as education and organizing tools.

What accounts for the support of European and North American governments for abusive dictators? Why is it so hard to persuade these governments, which are supposed to be democratic, to end support for actions that most of their citizens disapprove of?

Let's not fool ourselves. Without an informed and active and engaged citizenry to hold them to account, all governments, including Western governments, are going to conduct what used to be called a "realist" power- and economy-oriented foreign policy in the perceived interests of ruling elites. So, we have to apply the methodology of "naming and shaming" not only to abusive governments but also to their international allies.

We have to raise the cost to the U.S. government for its support of, say, Israeli and Saudi violations. It's not easy to raise that cost, because foreign policy tends not to be an animating issue in U.S. domestic politics, except where there is a specific domestic constituency. But the recent U.S. distancing from Saudi abuses in Yemen, and the beginning of a rethink on Israel, are not the result just of a change in administration; they are happening because Americans are holding their government's feet to the fire. At a time of Black Lives Matter, Americans are drawing parallels to Israel's treatment of the Palestinians.

Commentators frequently note the failure of the U.S. to prosecute American officials for torture in places like Abu Ghraib or Bagram, even though organizations like Human Rights Watch called for their prosecution. How do you think this affects the standing of the U.S.—to complain about torture in other countries or to sanction abusive officials in other countries, like Iran or Venezuela?

Of course it undermines the moral authority of the U.S. The U.S. had never been an unalloyed champion of human rights, at home or abroad, but it wasn't until George W. Bush that the U.S. openly embraced torture as a tactic. Governments from China to Zimbabwe were all too happy to point to the U.S. treatment of prisoners to deflect attention from their own conduct.

I wrote two Human Rights Watch reports and a book on why Bush, Rumsfeld, Cheney, Tenet and others should be held criminally accountable, but unfortunately Obama never wanted to invest the political capital in the effort. It's even difficult for me as an American lawyer to press other countries to bring perpetrators to account; I get Guantanamo thrown in my face all the time. Not a week goes by when someone doesn't ask why I am working in Africa when there are so many problems in the U.S. In fact, it's a question I often ask myself.

The ICC is in crisis. Its two efforts to prosecute non-African states—Israel for war crimes in Palestine, and the U.K. and the U.S. for abuses in Afghanistan—have led the U.S. to sanction the ICC staff and the U.S., the U.K. and Israel to sanction Palestinian officials, for pursuing a case against Israel. What do you think will happen with these ICC investigations? If the U.S. and its allies succeed in quashing these cases, does the ICC have a chance to survive?

The ICC is in crisis for many reasons. In almost 20 years, and at a total budget of almost $2 billion, the ICC has never achieved the final conviction of any state official, not just American or Israeli, but no one acting on behalf of any government anywhere. The only convicted people so far have been a handful of rebels and warlords.

The ICC has politically shown itself to be no match even for states like Kenya that control the crime scene and can manipulate the evidence and the witnesses. But the Palestine and Afghanistan cases, which cover clear war crimes committed by Israel, Hamas, the United States and the Taliban, will be its biggest test. The new prosecutor, Karim Khan, has the toughness and the smarts to stand up to the bullies—both the perpetrators of atrocity crimes and the powerful states that shield them. I just hope he also has the political will.

Our job as human rights professionals, in addition to developing the evidence and mobilizing public opinion, is to make the moral argument. I was at a meeting in The Hague with outgoing ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda in which Raji Sourani of the Palestinian Center for Human Rights looked her in the eyes and pleaded for the application of the rule of law to avoid the "law of the jungle"—to dissuade those who think that state violence and terrorism are the only answers to the Palestinian question.

For all its problems, the most important thing about the ICC is that it exists as a manifestation and an embodiment of the international community's stated commitment to justice. It sets the water level for justice around the world. A lot of what is happening at the national level wouldn't be possible without the umbrella, the example, or even the threat of the ICC.

Countrywide sanctions have had harmful effects on civilians, including most recently in Venezuela and Syria. Do you think human rights organizations should advocate for countrywide sanctions against any country?

I don't think that HRW, for instance, has advocated countrywide sanctions for many years. In 1998, when I was HRW's advocacy director, I led internal discussions on the use of broad economic sanctions, which had previously been part of the toolbox of Western human rights organizations. U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright had famously said that the death in Saddam's Iraq of a half a million children as a result of U.N. sanctions was "worth it."*

I saw first-hand the crippling effect of economic sanctions imposed repeatedly by the U.S. on Haiti—the richest country in the world using economic leverage to bring the poorest country in the hemisphere to its knees, including sanctions against the elected government of Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The former secretary-general of Amnesty International, Ian Martin, warned many years ago that "the human rights movement cannot be happy in working through the existing power relationships in an unequal world, nor can it even be neutral in its attitude to them." Human Rights Watch's position today is to support so-called "smart" or targeted sanctions, such as asset freezes and travel bans, which aim to pressure an abusive leadership while "minimizing" negative impacts on the humanitarian needs of the general population. I haven't monitored how that has worked in practice, but it should be obvious that driving nations further into poverty is not a human rights solution.

The debate over "justice vs. peace" has sometimes found Human Rights Watch in opposition to the voices of local groups. It may demand a better peace treaty with more accountability for abusers than local groups, whose priority is peace. This recently happened in Colombia in connection with the government's peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or the FARC. Do you believe that human rights organizations are responsible for taking into account the political consequences of absolutist demands for justice?

I can't speak to the Colombia situation because I just don't know enough. As international activists, it's important that we insist on upholding norms and on punishing those who commit atrocity crimes. Justice is a potentially messy and conflictual affair that requires the investment of political capital, but we need to understand that long-term peace, which goes beyond the immediate need to end a conflict, requires justice and accountability. Where mass atrocities are not addressed, when victims' demands for justice are not heard, the danger of a return to violence often remains high.

That said, solutions must be locally led, not imposed from the outside, and approved through democratic processes including by the victims. It's not my place as a foreigner to tell Colombians or South Africans—especially the victims of state or rebel crimes—how they must design their transition to a peaceful future.

Although Human Rights Watch never explicitly advocated for U.S. military intervention in Syria and Libya, some of its leading staff made comments that made it clear they supported such military intervention. Should a human rights organization ever be in the business of urging the U.S. to take unilateral military intervention against another country without U.N. permission?

Recourse to force is not only legitimate but also morally imperative in the face of mass atrocity. The question is who decides, and who intervenes—and how. I wouldn't necessarily make U.N. Security Council permission an absolute requirement, because we've seen that its permanent members can use their veto power to block collective international action.

But we can't accept the unilateral use of military power—by the U.S. or anyone else. Having worked in Chile, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Haiti, Chad, I am inherently skeptical of the uses of U.S. power. But having witnessed the failure of the international community to halt the genocide in Rwanda and ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, I know that inaction is not an option either.

We also need to be humble about what military intervention can achieve. I was in Libya under Qaddafi, and it was suffocating. The repression got worse after the uprising, but look at how the Western intervention turned out—not just for Libya, but for the entire Sahel region, which is now in chaos. The invasion of Iraq got rid of a cruel dictator, but it invited and emboldened violent jihad throughout the region and exacerbated sectarian conflict. It would be hard to argue that these interventions improved the human rights of the people in the regions.

![Security forces loyal to the interim Syrian government stand guard at a checkpoint previously held by supporters of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, in the town of Hmeimim, in the coastal province of Latakia, on March 11, 2025. Syria's new authorities announced on March 10, the end of an operation against loyalists of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, after a war monitor reported more than 1,000 civilians killed in the worst violence since his overthrow. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the overwhelming majority of the 1,068 civilians killed since March 6, were members of the Alawite minority who were executed by the security forces or allied groups. (Photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR / AFP) / “The erroneous mention[s] appearing in the metadata of this photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR has been modified in AFP systems in the following manner: [Hmeimim] instead of [Ayn Shiqaq]. Please immediately remove the erroneous mention[s] from all your online services and delete it (them) from your servers. If you have been authorized by AFP to distribute it (them) to third parties, please ensure that the same actions are carried out by them. Failure to promptly comply with these instructions will entail liability on your part for any continued or post notification usage. Therefore we thank you very much for all your attention and prompt action. We are sorry for the inconvenience this notification may cause and remain at your disposal for any further information you may require.”](https://dawnmena.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/syria-22039885951-350x250.jpg)

![Security forces loyal to the interim Syrian government stand guard at a checkpoint previously held by supporters of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, in the town of Hmeimim, in the coastal province of Latakia, on March 11, 2025. Syria's new authorities announced on March 10, the end of an operation against loyalists of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, after a war monitor reported more than 1,000 civilians killed in the worst violence since his overthrow. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the overwhelming majority of the 1,068 civilians killed since March 6, were members of the Alawite minority who were executed by the security forces or allied groups. (Photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR / AFP) / “The erroneous mention[s] appearing in the metadata of this photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR has been modified in AFP systems in the following manner: [Hmeimim] instead of [Ayn Shiqaq]. Please immediately remove the erroneous mention[s] from all your online services and delete it (them) from your servers. If you have been authorized by AFP to distribute it (them) to third parties, please ensure that the same actions are carried out by them. Failure to promptly comply with these instructions will entail liability on your part for any continued or post notification usage. Therefore we thank you very much for all your attention and prompt action. We are sorry for the inconvenience this notification may cause and remain at your disposal for any further information you may require.”](https://dawnmena.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/syria-22039885951-360x180.jpg)