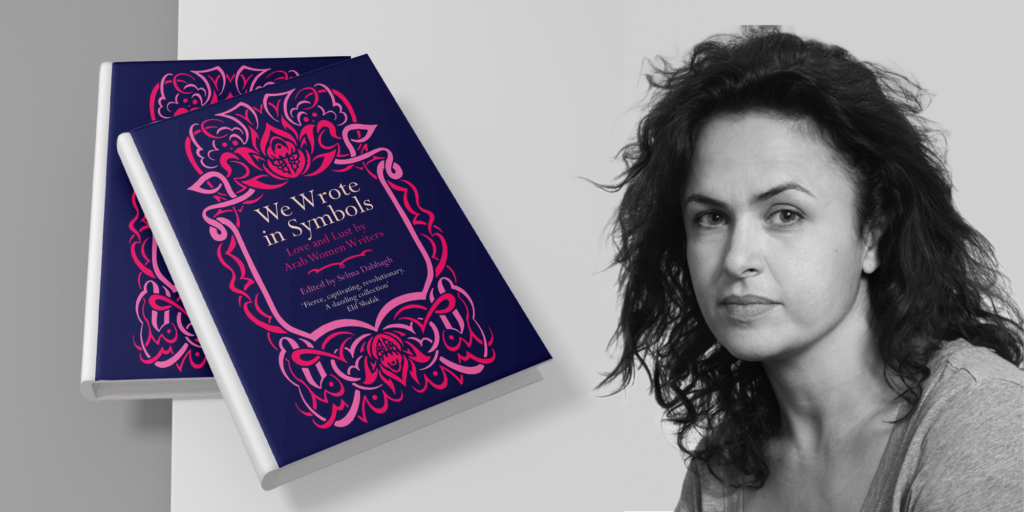

Selma Dabbagh is a British Palestinian lawyer and writer of fiction who lives in London. She is the author of the novel Out of It and the editor of We Wrote In Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers.

Editor's note: The following excerpt is adapted from the introduction to We Wrote in Symbols: Love and Lust by Arab Women Writers (Saqi Books, 2021), edited by Selma Dabbagh.

عربي

Showcase No. 38 of the National Museum of Damascus contains a tiny figurine identified as Ishtar, the ancient goddess of beauty and love. The catalogue says she was made in the city of Ur in around 2500 BCE. The curvaceous figurine stands naked and wide-eyed, ready to challenge the centuries to come. If anything symbolizes the spirit of this book, it is the sight of her tiny, tightly clenched fists.

We Wrote in Symbols is a selection of writing on love and lust over three millennia, that is often, but by no means always, celebratory. Here are over 100 pieces of prose and poetry written in different languages and many styles. All the authors, wholly or partly, may be considered Arab women writers. Some of these women are living and some are long deceased. They are the voices of all ages, and range from highly acclaimed to the emerging. Several writers have never been published before – others are well known in other languages, but appear in English here for the first time. Names and dates can't be attached to some of the oldest works, and some writers chose to use pseudonyms. They are, or were, residents of towns and cities from Andalusia to Baghdad, Beirut to Berlin, Damascus to New York.

As a writer whose parents are English and Palestinian, We Wrote in Symbols is an exploration into a part of my heritage. As a teenager in 1980s Kuwait, I grew up, like many teenagers, in opposition to my location, which appeared to me to represent confinement. This collection is the product of a – not untroubled – love affair with the Arab world, which I came to later. As an adult, I lived in and visited other Arab countries (Bahrain, Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria). Through experiences and the work of writers, historians and translators I discovered a diversity, spirit, warmth and humor that is admired throughout this book.

It feels important that a book like this should exist – to the best of my knowledge there is not another one like it. It was fated to be an eclectic collection. The works range in approach and style, from the assured, sensitive love poems of Naomi Shihab Nye, Nathalie Handal and Samira Negrouche to the explicit thrusts and plastic gloves in Mouna Ouafik's short verse; from the arch, provocative tone in Joumana Haddad's narrator's visit to a swingers' club to the vexed intellectual narrator of Rasha Abbas. The point of view switches from complex male protagonists, to housebound housewives, imperious princesses and indignant witty foul-mouthed slaves. But the intensity of feeling remains.

Many pieces here have been translated. To translate writing about love and lust, in tones often subtle but highly charged, is uniquely challenging. English – imbued as it is with puritanical sensibilities, with a frequently blunt approach to erotic writing – is not an easy landing point. In French and Italian, to say that you have had "a story" with someone ("une histoire" / "una storia") clearly denotes that love and lust were involved. The word "qissa" in Arabic can in many contexts denote the same. I like the idea of romantic associations being imbued in the word for "story." Stories and love affairs form part of our worlds; they are histories which live in our present and inform our futures.

To try to pretend that the Arab world has experienced a sea change in its approach to women's sexuality would be a misrepresentation. But women's writing in the Arab world and beyond has become more daring, experimental and creative in recent years.

- Selma Dabbagh

In Baghdad, a couple of millennia after the little Ishtar figurine was molded, but still more than 1,000 years ago, a female poet was allowed entry into an elite literary salon. The poetry of the Majiun group focused on the erotic, the bawdy and the lewd. The poet Inan Jariyat an-Natafi (d. 871 CE) become one of its first female members, if not the only woman there. Her talent was the envy of others, including her friend the poet Abu Nawas, whose name has come to be synonymous with wine poetry. Only recently has the work of this group of Abbasid poets (known as the "Lewd Ones") been given the serious consideration it deserves. Subject matter aside, these witty, humorous poets demonstrated "unprecedented experimentation with poetic device, form and diction," playing an important role in the modernization of Arabic poetry.

The intricate art of seduction flourishes at times of prosperity and peace, as well as under societal duress and enslavement. The Abbasid court of Harun al-Rashid of The Thousand and One Nights fame, and the worlds of Umayyad and Andalusian palaces, are reminiscent of the complex sexual intrigues found in the Venetian Republic in the eighteenth century. Social mobility for a concubine in the Abbasid court was partly dependent on verbal, sexual and musical skills in the way that soldiering skills were essential for male slaves during the later Mamluk era.

During the Umayyad (661–750 CE) and Abbasid periods (751–1258 CE), economic prosperity and the questioning of socio-religious taboos "helped create a society bent on enjoying Allah's earthly gifts to full." In the later Andalusian period (711– 1492 CE), the Arabs turned the Iberian peninsula of al-Andalus into a "paradise on earth." During these eras there is evidence that it was common for love poems to be transmitted secretly via intermediaries. The recipient's name was often changed, female names being replaced by male ones and vice versa. Lines from poems went back and forth between lovers – not just as missives, but embroidered onto everyday items of all kinds, including sashes, slippers and turbans. These pithy declarations not only voiced desires, but grievances too, and not just to the object of these feelings, but to anyone in the court (or the street) who cared to read them.

It is not known how classical poetry was received or circulated at the time, but there is no doubt that in the subsequent centuries these poems were curtailed, controlled, rewritten or otherwise prevented from being shared. This extended moratorium was caused mainly by more orthodox, proscriptive interpretations of monotheistic religions prevailing, along with high levels of female illiteracy and greater sexual conservatism in general. Of works that have survived, there are few. A couple of centuries after Wallada bint al-Mustakfi (d.1091) embroidered on her robe "I walk my walk and boast in pride," women's writing on love and lust disappeared, almost entirely, corresponding approximately with the "fall" of Andalusia in 1492, when Muslim and Jewish populations were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula. It was not to revive again for several hundreds of years: an extended blackout of half a millennium.

In the late nineteenth century, a tentative return to addressing the subjects of the erotic was made again by "novelists writing in Arabic, in Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, who challenged the practices of marital courtship and particularly arranged marriages, as against the desires of young people," according to Professor Marilyn Booth. Although she wasn't the first, Zaynab Fawwaz challenged these norms in both fiction and newspaper essays. Her debut novel (translated here for the first time by Professor Booth) linked love and respect to good political practice. She also wrote an extensive biography of the lives of historic women figures in the Arab world and Europe, to show just how much women were capable of. By the twentieth century, writing by women was picking up momentum again, often in novels, which was a newer form of literature in the Arab world compared to poetry. Arab women returned to writing about love with increasing clarity and self-assurance. The writing grows from this period onwards in literary creativity, style and variety – a trend which has continued to increase into the twenty-first century.

To try to pretend that the Arab world has experienced a sea change in its approach to women's sexuality would be a misrepresentation. But women's writing in the Arab world and beyond has become more daring, experimental and creative in recent years. The exuberant voices and experimentation of the classical periods echo through the centuries.

Selma Dabbagh

Source: graphic by DAWN

The writers in this anthology are of the three main monotheistic religions, or of none. Some lived before their respective prophets were even born. They include academics, archivists, biographers, doctors, engineers, homemakers, lawyers, mothers, playwrights, performers, professors and novelists, as well as medieval concubines, court singers, princesses and political exiles. Many have public profiles as political actors for change, such as Ahdaf Soueif, Hanan al-Shaykh, Shurooq Amin, Rita El Khayat, Joumana Haddad, Mouna Ouafik and Leïla Slimani. A large number of the authors have had their works banned in their countries of origin and beyond. Their fearlessness and articulacy have enabled other women to write, act and forge a space for themselves with greater confidence.

The Arab world is largely united by a language whose origins predate the monotheistic religions but is, of course, strongly bound and preserved as the language of the Holy Qur'an. Although the Arab and Islamic worlds are distinct from each other, the influence of the Islamic religion since its birth in the seventh century has prevailed across the Arabic-speaking world. It is worth noting (with a brevity that puts me at risk of distortion) the religion's relevance to this collection, because Islam's approach to female sexuality is distinctive. As the pioneering sociologist Abdelwaheb Bouhdiba puts it, "the Qur'anic exercise of sexuality assumes an infinite majesty." Sex does not have to be for procreational purposes, it can also be for its own sake and contraception was permitted. It is a union and an art form to be cherished and respected. The giving and receiving of sensual pleasure, within prescribed relationships, is viewed as enhancing the harmony of marital union and society at large, providing the believer with an insight into the nature of heaven while still on earth.

Throughout history we find writing that juxtaposes mortal sexuality with celebrating love of God and religious festivities. This has always proved uncomfortable to some. The juxtaposition of ecstasy in sex and religion, it must be noted, has also provided ripe subject matter for song lyrics throughout time – contemporary hip hop artistes Missy Elliott and Kelis boast their sexual prowess and praise the divine in the same breath, for example. During the heyday of the Egyptian night-club scene in the 1920-40s, Arab women were center-stage performers challenging patriarchal ideas of what was, and wasn't, acceptable for women to say and do in public. Many female singers played a role in composing the lyrics they sung, but little documentation of the song-writing process has survived. Heba Farid, granddaughter of the singer Naima al-Masriyya, provided me with a sample of the types of lyrics her (fairly shy and conservative) grandmother sung at the time: Com'on, big boy, let's go to the Qanate / Do me a favor, don't be my mood killer.[1]

In certain eras and places, women's capacity for sexual desire has been accommodated and eulogized. Court records show that there was a time in Abbasid history when women could seek a divorce on the basis that they were not satisfied with their husband's sexual performance. Quality foreplay became a serious matter worthy of scholarly attention. Abbasid scholars would expound on erotology in the same way that they would write on minerology, or astronomy, with the sciences frequently appearing in the same work.

At other points in history, women's capacity for sexual desire has been used as a reason to censor them. Threats made against women for expressing lust in person or in their writing have been made persistently throughout the ages. The pre-Islamic poet Jariyat Humam ibn Murra was killed after reciting the poem in this collection. Prohibitions, even if they are not used as an overt sanction, have a chill factor and set a challenge for writers, who can be shamed by friends, family and community if they write about such liaisons, even in a fictive way, without hiding their identity. Male writers are under far less scrutiny when it comes to the behavior of their characters. It appears to be a universal trait to associate sexually explicit writing with the behavior of the writers, in a way that writing about say crime fiction, does not lead to aspersions of criminality in its authors.

However the illicit is hard to police and often adds fuel to desire, as I discovered at banned teenage parties in Kuwait. Sensuality and liberality do not necessarily go hand in hand. The harem, represented most frequently as a place of dulled imprisonment, could also provide solace, solidarity, intrigue and protection from the public sphere and men; a place of sensuality between women and a place to exchange sex tips and advice. Prohibition also gives rise to rabid hypocrisy, creativity when it comes to subversion, mind-bending wars of nerves, ludicrous situations, hilarity in camaraderie – all wonderful material for the writer's pen.

In most Arab countries today, same-sex relations are banned by law, and sexual minorities live and love under threat from persecution. Regardless of what Arab women writers may do or say in the real world, even to write fictively of these relationships is a risk. There is great vulnerability here.

- Selma Dabbagh

The love of women by women has been described in both coded and celebratory terms throughout history. Ulayya bint al-Mahdi, the sister of Hurun al-Rashid, loved men, women and a court eunuch, to whom the poem We Wrote in Symbols, is addressed, according to Dr Marlé Hammond. To put these works into context it should be noted that, during early periods of Islam and pre-Islam in the Arab world, sexuality did not have the heteronormative assumptions that existed elsewhere at the time. It was not until the Western imperial legacy, including the works of Sigmund Freud, crossed the Mediterranean into the Arabic language, that categorizations began "erasing the more extensive and flexible medieval Arabic model of sexuality, declaring it 'deviant' [imposing] instead a binary view of sexuality onto the Arab world."

In most Arab countries today, same-sex relations are banned by law, and sexual minorities live and love under threat from persecution. Regardless of what Arab women writers may do or say in the real world, even to write fictively of these relationships is a risk. There is great vulnerability here.

*

The pieces in We Wrote in Symbols also move geographically. Not all of them are set in the Arab world – far from it. Love and lust know no borders. Farah Barqawi's narrator in Four Days to Fall In and Out of Love can only find the freedom she craves by travelling to Europe, reversing the voyages of nineteenth-century writers like Gustave Flaubert who fled bourgeoise provincialism to seek sensuality in the East. Abbas's heroine is in an unnamed European city. Salomé's is set in a field in the West Country of England.

The reader is encouraged to find connections between the works and the times in which these women wrote, for the human heart never grows up, nor have the body's desires changed through the ages. Recurring themes include the idea of innocence, as symbolized by virginity in the extract from The Almond by the pseudonymous Nedjma, as well as in the poetry of Shurooq Amin and in Rita El Khayat's Skin. For Amin and Nedjma, sex and love, "re-virginizes" them, to paraphrase a line of Amin's poem Hymen Secrets: Girl with a Box. Hand in hand with virginity comes the idea of the wedding night, the focus of the excerpt from Isabella Hammad's The Parisian, where politeness both separates and bonds the newlyweds, and Suad Amiry's Yummy as Kibbeh, where the bride does not share the taste, or experience, of her relatives when it comes to the joys of sex, which has been sold to her in culinary terms. It is rewarding to look for patterns in theme, content, language, voice and approach in these texts from across the centuries. Much has changed. Much has not.

[1] Translation from Arabic by Frédérik Lagrange and Claire Savina. Reproduced with permission of the translators and Hiba Farid of the Na'ima Masriyya project.