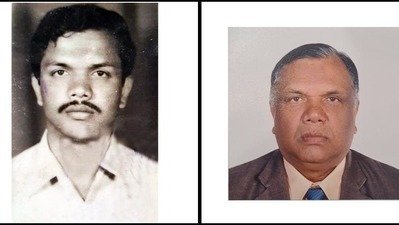

Ahmed Abdulumer’s father, an Indian national, was a foreign worker in Saudi Arabia from 1981 until 2020.

It has been called a form of modern-day slavery. The abusive "kafala" or sponsorship system for foreign workers in Saudi Arabia gives their employers near-absolute authority over their legal status in the country, including their ability to leave a job. The kafala system applies to millions of migrant workers in the kingdom who account for more than 80 percent of the private sector workforce, making them the labor foundation of the Saudi economy. The Saudi government claimed to introduce labor reforms in 2021 that would curb the kafala system. But those "reforms" have proven to be empty promises—as my father's mistreatment painfully showed.

My father, an Indian national, was a victim of human trafficking and forced labor in Saudi Arabia. His story is just a glimpse at the widespread abuse of migrant workers in the kingdom, an oppressive labor system that is at the root of all of Saudi Arabia's grand economic plans under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, widely known as MBS.

My father, Ahmed Abdul Majeed, arrived in Saudi Arabia in 1981, from India, to work as a sales manager. He spent 40 years working for a single company, a Saudi travel agency now known as the Seera Group, which is controlled by the crown prince through the Public Investment Fund (PIF), the sovereign wealth fund that he chairs. Seera Group, which had for years been the largest travel company in Saudi Arabia, is now the largest travel business in the Middle East.

My father's job entailed working around the clock serving many uberwealthy business clients, royal family members and diplomats every single day of the year, including holidays. He built up a reputation at the company for his honesty and dedication to his work, serving many of his clients for decades. Yet nearly four years ago, at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the company decided to abruptly terminate him. My father immediately informed his employer that he wished to go back to India and tend to my ailing mother, who had a critical, life-altering surgery due. This marked the start of his nightmare.

My father's story is just a glimpse at the widespread abuse of migrant workers in the kingdom, an oppressive labor system that is at the root of all of Saudi Arabia's grand economic plans.

- Ahmed Abdulumer

Under the kafala system, my father required the company's approval to leave the country. Seera's management declined his request and instead devised a scheme to force him to keep working, without pay, to collect their clients' overdue balances. This was normally the responsibility of the company's finance department. In the event that clients refused to pay their balances, Seera's legal department was supposed to be responsible for suing the customers for the funds.

Instead, the management forced my father, at the age of 63 and during the height of the pandemic, to essentially panhandle at different client offices in Riyadh, begging them to pay their bills to the company that had fired him and still controlled his fate. He was trapped doing this forced, unpaid labor for six months, from March until September 2020, when his work visa expired. Despite the deadly health risks of COVID-19 in those early months of the pandemic, he still didn't receive any compensation. He had to borrow money from friends to feed himself and keep a roof over his head. This humiliating abuse was inflicted on a man who had spent four decades of his life working in Saudi Arabia, but was discarded like a piece of trash, as if his work meant nothing, as if he himself was disposable. My mother's health had deteriorated rapidly during this time, and my father begged the company to let him leave the country to attend to her. They refused.

In the end, with the clock running out on his visa and Seera's clients categorically refusing to pay their balances because of the uncertainty of the pandemic, the company forced my father to pay the dues himself, out of his own pocket. It was extortion. He was forced to sell property and other assets in India to raise the money. Only after transferring that money to the Saudi company that had effectively become his captor was my father finally able to free himself and leave the kingdom, just before his visa expired. Before he escaped Saudi Arabia, though, there was one final insult. Despite working for a major travel business, he had to purchase his own ticket home to India—another blatant violation of Saudi labor law, as employers under the kafala system are supposed to pay for a worker's airline ticket home. This wage theft cost my father all his hard-earned retirement savings.

After finally arriving back home in India, my father pleaded with Seera Group to at least reimburse him the money for my mother's surgery, but the company never replied. The entire ordeal caused a significant delay in my mother's surgery, and the complications are likely to lead to life-long health issues for her.

Back in India, my family vowed to fight for justice. He contacted the prime minister's office in New Delhi to request their assistance. According to the Indian government's own figures, there are nearly 2.5 million Indian workers in Saudi Arabia, making them the largest community of foreign workers in the kingdom. An estimated 9 million Indians work in the Gulf region; the United Arab Emirates host the most, some 3.5 million Indian workers. The prime minister's office forwarded the case to the Indian Embassy in Riyadh, which in turn asked Seera Group to resolve the matter. There was no reply from Seera, despite multiple requests from the embassy, and the matter was soon considered closed by the Indian government.

A man who had spent four decades of his life working in Saudi Arabia was discarded like a piece of trash, as if his work meant nothing, as if he himself was disposable.

- Ahmed Abdulumer

I persuaded my father to come to the United States, where I live. There could be no better place to fight this battle, I thought, than the country built on democratic principles and the rule of law. My father traveled in person to the Saudi Embassy in Washington shortly after his arrival and forwarded the case to the Saudi ambassador, Reema bint Bandar bin Sultan. But there has been no reply even after two years.

We managed to get my father's case published in a report last year on human trafficking in Saudi Arabia by the Human Rights Foundation, based in New York. The report exposed the "deep-rooted and interconnected web of oppressive practices," including the kafala system, "that facilitate human trafficking" in the kingdom. It was unequivocal about what my father had endured, describing his abuse as "entrapment and forced labor." I sent a copy of the report to Badr Al Asaker, a close confidante of MBS and the head of the crown prince's private office, with all the details about my father's case. I never received a response.

According to the Human Rights Foundation, my father's case showed that the Saudi regime is not just "inadvertently" benefiting from these exploitative migrant and labor policies, but is in fact "explicitly complicit in committing the same egregious acts and profiting from them," since my father worked for a company controlled by MBS, via the Public Investment Fund. As the Human Rights Foundation concluded, my father's abuse and the abuse of other foreign workers and migrants in Saudi Arabia detailed in its report are "part of a larger, systematic pattern of entrapment and trafficking that impacts no single nationality or background" in the kingdom.

MBS has declared his "Vision 2030" for the post-oil Saudi economy and is seeking gargantuan sums of foreign investment for his pet projects. But that "vision" relies on the rampant abuse of millions of foreign workers in Saudi Arabia, like my father, who spent 40 years of his life toiling in the kingdom only to be trapped in forced labor and extorted by his employer before he could escape home.

Even after nearly four years, my family's suffering has not ended, but I will not and cannot remain silent. I can no longer bear to see my father and my family suffering mentally, emotionally and financially. I know we are not alone. I can only imagine how many others are still suffering from their own nightmares of working in Saudi Arabia.