Juan Cole is the Richard P. Mitchell Collegiate Professor of History at the University of Michigan. He is also a non-resident fellow at DAWN and a non-resident fellow at the Center for Conflict and Humanitarian Studies in Doha.

Juan Cole is the Richard P. Mitchell Collegiate Professor of History at the University of Michigan and a Non-Resident Fellow at DAWN

Alaa Abd-El Fattah, a young man who loves his country, is locked up in Tora maximum security prison 2 for the crime of protesting. Since many millions of Egyptians have protested in recent years, the software engineer is clearly being singled out for punitive treatment because of his fame and influence as a long-time blogger and activist.

Alaa, as he is affectionately known among Egypt's restive youth activists, played a central role in the popular demonstrations in 2011that deposed former Egyptian general-turned-president Hosni Mubarak. In the bloody aftermath of the military coup against the elected government of President Mohamed Morsi in the summer of 2013, he continued to speak out. That fall, he was arrested for participating in a protest – after the junta arbitrarily declared that demonstrations must be cleared beforehand by the state.

It is fair to say that the Egyptian officer corps does not entirely understand the concept of people's protest.

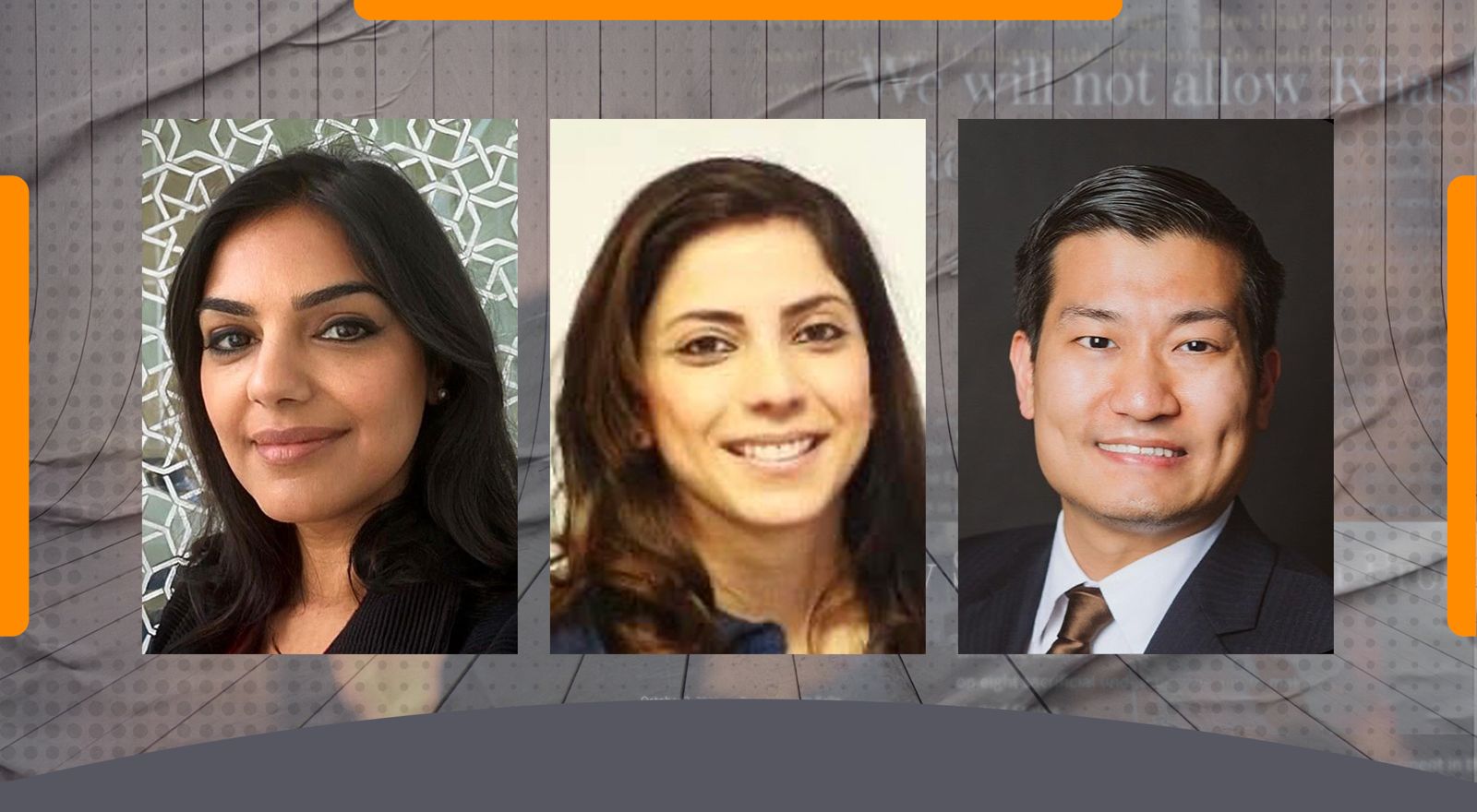

Meeting in the notorious Tora prison complex on September 29th, a three-judge panel comprised of jurists Wagdy Abdel Moneim, Ali Omara, and the chair Mohamed Said al-Sherbiny, renewed Alaa's imprisonment for an additional 45 days – supposedly while he is being investigated on charges of spreading false news injurious to national security and belonging to an organization founded in such a way as to contravene both statutes and the constitution. It appears that the military's illegitimate legal system views Alaa as a serious threat to rule of law in Egypt – and not just Alaa. His lawyer, Mohammed el-Baqer, a well-known human rights defender and director of Adala Center for Rights and Freedoms, was also arrested that same day and also subjected to ill-treatment at that same prison.

Locking up and mistreating Alaa Abd-El Fattah, Mohammed el-Baqer, al Jazeera journalist Mahmoud Hussein, human rights defender Bahey El-Din Hassan, and tens of thousands of other independent voices of conscience in Egypt's brutally mismanaged prison system during the coronavirus pandemic is a potential death sentence. Despite this clearly foreseeable risk, the Egyptian authorities have refused to offer such prisoners conditional release, while at the same time granting freedom to thousands of non-political prisoners.

Alaa was released briefly on bail in 2014, but then sentenced to five years in prison in 2015. He obtained a daytime limited parole in March of 2019, with the restriction that he had to report to jail every evening and spend the night.

When protests broke out in fall, 2019, Alaa was rearrested without charges or any semblance of habeas corpus. His sister, the activist Mona Seif, wrote in a public letter that "on the night of Alaa's arrival to Tora maximum security prison 2, he was stripped of his clothes, blindfolded, beaten, and threatened that 'he will never get out of here.'"

With the outbreak of the coronavirus this past spring, the military government banned visits to prisoners by family and friends, and even telephone calls and letters, on the pretext that it risked the spread of infection. Public health specialists worried that the crowded conditions in Egyptian prisons would cause a dangerous outbreak among the prisoners. Four brave women – Alaa's mother, Leila Soueif, his aunt, the prominent novelist Ahdaf Soueif, his sister Mona, and political scientist Rabab El-Mahdi – staged a small demonstration in downtown Cairo asking for the conditional release of prisoners during the pandemic on humanitarian grounds. They were swiftly arrested, but later released.

In April, Alaa launched a hunger strike to protest his complete isolation. The prison authorities declined to inform his family of this development. Only when he ended it in May was he allowed to send them a letter saying that he had begun eating again. He wrote that since his case had at last been taken up by an Egyptian court, he was content to let the legal process proceed.

His mother, Leila, and sisters Mona and Sanaa gathered in June outside the Tora prison in hopes of receiving another letter from Alaa, whom they had not seen and to whom they had not spoken for months. They say they were attacked by a group of women. Then on June 23, Sanaa was arrested by the Egyptian authorities and charged with defaming the state, interfering in its operation, spreading false information through her social media accounts, and even terrorism. On September 11, Sanaa was arraigned on charges of spreading lies about the conditions in Egyptian prisons.

The treatment of Abd-El Fattah and his family members epitomizes the travesties against the rule of law that have characterized every facet of the government of Field Marshall Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, including manipulation of the entire legal system from courts to prisons, judges to jailers. Sisi – despite having taken off his uniform and run for office in obviously phony elections – remains merely a mouthpiece for the same military junta that in 2013 brutally deposed Egypt's only democratically elected government, massacred thousands of peaceful protesters, and continues to jail political dissidents with no accountability.

Meanwhile, the United States government continues to pay lip service to human rights while providing the Egyptian junta with wink-wink diplomatic immunity and $1.38 billion in annual aid like clockwork, almost all of it military. Congress should rethink the legality and morality of backstopping a regime that is notorious for its egregious violations of basic freedoms of speech and assembly.