Tam Hussein is an award-winning investigative journalist and writer who has reported on jihadist networks, foreign fighters, trafficking and crime. His work has been shortlisted for the Orwell Prize for Journalism. An associate editor at New Lines magazine and a specialist producer for ITV News, he is the author of "To The Mountains: My Life in Jihad, From Algeria to Afghanistan," "The Travels of Ibn Fudayl" and "The Darkness Inside."

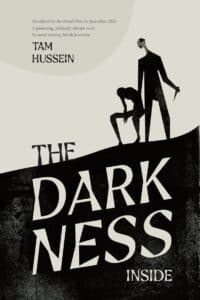

Editor's note: The following excerpt is from Tam Hussein's debut novel, The Darkness Inside.

The genesis of The Darkness Inside was purely coincidental. I started writing it initially as a screenplay, after working with director Peter Kosminsky on a four-part drama series, The State, about young ISIS recruits from Britain. It gave me insight into the writing process for a television drama, and Kosminsky was very encouraging. Actor Riz Ahmed even got in touch to ask if I wrote screenplays for dramas and if I might work with some of his writers in the BBC writers' room. There was one piece of advice from Ahmed I didn't listen to: "Unless it's comic book stuff, most stories are now for TV, not film."

I wrote a three-part screenplay about foreign fighters and jihadists in Syria and went to a production company, where I sat in front of an executive who clearly hadn't bothered to read it and instead came up with an absurd idea of comic book proportions: "What if Jihadi John returned?" I don't know what sort of caricatures the man had playing inside his head.

I realized that perhaps screenplays couldn't really deal with this topic as I hoped. As a journalist, I had also focused on Afghanistan, which I believe in many ways is the cradle of modern jihadism. Understanding the Soviet war in Afghanistan and the resistance of the mujahideen is crucial to any reporting on jihadism today. For this reason, I worked with Algerian Islamist Abdullah Anas to co-write his memoir, To The Mountains: My Life in Jihad, From Algeria to Afghanistan. One of the first Arabs to join the Afghan mujahideen, Anas later fell out with Osama bin Laden and what became al-Qaida. He dedicated the book to the memory of his friend Jamal Khashoggi.

But I still wanted to document the stories of foreign fighters and jihadists in Syria's civil war, because it remains an untold story. Covering jihadism, and especially foreign fighters like those depicted in The State, has become increasingly difficult in the United Kingdom, though, where anti-terror legislation has had a cooling effect on the media and publishing industry. Whenever I suggested the project, publishers would fear that they would be presented with a production order from the police, and they would be forced to hand over the manuscript.

So how does one tell the story of these men? Even if my screenplay had been optioned, a colleague had advised that it might sit in the drawer of the executive and rot for years. I decided, then, to turn it into a novel, knowing fiction can allow a writer to divine truths that nonfiction cannot.

In my mind, it had to be a compelling detective story that also, like a Henrik Ibsen play, made the mundane profound. So the story begins with something mundane: the stabbing of Anis, a young man in South London. To Sid, the journalist protagonist, he is yet another statistic of Sadiq Khan's London, and a story worth chasing. Yet as Sid begins to investigate his death, he discovers that Anis had been a foreign fighter in Syria, and it is this experience that got him killed back in London.

This is the story of the seemingly ordinary men who walk among us—who were once "emirs" in Syria and now, having returned to the U.K., go back to their old, mundane lives. Even though the war has left an indelible mark on their souls, they can tell no one of their past for fear of being caught by the law.

The Hospital

Days before the assault, Sami couldn't recall a time when the enemy had dropped so many barrel bombs in one area. He thought that the hospital in Owaija district, Aleppo, was the very incarnation of evil. That hospital had been perverted and used to garrison men, store munitions and extract confessions with pliers or with an unzipped fly if necessary. Due to its height the enemy directed artillery fire, MiGs, snipers and God knows what else against them. It was crucial to securing the East/West and North/South supply routes. It had to be taken out, whatever the cost.

The hospital was alienated from itself and resembled one of those miserable little council estates built during the seventies in Croydon. They looked like they were born from the same father. Both were located close to some brokeback area where the poorest citizens lived. If Owaija's people didn't have the tribe, family, honor and religion they would have carried on like those miserables in Croydon. They'd probably have ended up like Anis, standing on the roof somewhere billing up a spliff with some friends and looking down on passers-by, sending down some phlegm and watching it find its target. But these things were unheard of in Owaija.

Sami had learnt from an Algerian fighter who used to be a geography teacher with a penchant for weird facts that Gamal Abdel Nasser had built Kindi Hospital in the 1950s when Syria had decided to unite with Egypt. It was built as a sign of the dictator's benevolence; to treat cancer patients with an iron fist. How and why the Algerian knew that the hospital had had two hundred and fifty doctors and six hundred and fifty nurses and was affiliated to the Aleppo Medical Hospital in its heyday was beyond Sami. Perhaps knowing random facts was a sign of intelligence.

Sami and Abbas trudged towards their car in Owaija when they came across some Jazrawis in fatigues, black woolen hats and fingerless gloves. They were climbing over the rubble where a barrel bomb had fallen only an hour ago and they were optimistically searching to see if there were any survivors. Abbas peered at Sami. "No one's alive akhi," he said and kept on walking. "No one survives a three-story house falling on top of them. If you can't put a plaster on a crushed face better treat them like an injured dog and take them out of their misery."

"But shouldn't we just check?" said Sami. "You know just in case?" He pulled at his long, magnificent beard; he did that whenever he was agitated. It was a habit from his school days. His lack of a chin meant his classmates nicknamed him "chinless." For five years he pulled at the chin as if he was willing it to grow, but no chin of note ever came, just spots. Sami's beard resolved all of that but the habit never left him. The long beard jutted out and gave the impression that he did have a chin. It was aesthetically pleasing.

"They are gone," Abbas reiterated and he went on his way. Sami kept on staring at the efforts of the Saudis and reluctantly followed. His eyes still scoured for life beneath the rubble. But the Saudis hadn't given up; they were still removing rubble, peering through the twisted steel and concrete. In the distance he could hear the sirens and cars moving towards the site.

Sami's eyes fell on an old woman with tattoos on her face, wrapped in a shawl, wearing thick socks and sandals and sitting on the apex of the rubble clutching her black plastic bag with some vegetables and what looked like warm bread. Her hand was holding on to a tiny little finger that was either going blue from the winter cold or rigor mortis. She was talking gibberish, sometimes reciting the Quran, sometimes wailing, sometimes screaming: "All I wanted was bread! Just that! That is all I wanted for my family and then you come along and Bashar takes three generations of my family! May God curse you!" In some ways she was right; the barrels were falling because the enemy knew something was afoot with the hospital.

That morning Sami had been cracking up as he overheard the radio conversations passing between the enemy. One of the soldiers was saying: "I can see beards, I can see beards… I can see men wearing thobes… I can see men wearing thobes… over," and the other guy was replying: "They are al-Qaida you idiot… they are al-Qaida you idiot… what do you expect?!"

They left the Saudi Jazrawis for Sheikh Najjar and sat at a busy shawarma stall, heating themselves on a diesel stove, drinking warm tea and waiting for their order. Winter in Aleppo was colder than in London.

"I don't know how long this operation will last," Sami said, rubbing his hands over the diesel heater. They had tried to take the hospital eleven times already and the enemy had become even more entrenched.

"Eleven times!" said Abbas, exasperated. "Why didn't they try to take the place with an Istishadi?"

"They did."

"They did?" said Abbas, scratching his eye. "What happened?"

"He blew himself up a bit too early," Sami said, grinning.

"May God accept him," said Abbas, laughing irreverently and shaking his head. "Some of these guys are a bit too eager."

No one could figure out how the enemy had held out for so long without the Liwa Tawheed rebel battalion knowing about it. The general consensus was that Liwa Tawheed boys must have been taking bribes and, in return, supplying the enemy with food, water, prostitutes and everything else they needed.

About three hundred rebels including Sami and Abbas were going to carry out the attack on the hospital. They had trickled in from all over the countryside during the build-up consisting of artillery fire. Radio was officially in charge of the operation —that was what the council had decided. Other boys were arriving from Homs, Hama and Lattakia. The Nusra boys and the North African battalion, Sham al-Islami, seemed to be the most organized and everyone apparently knew who was meant to do what, down to who made the tea. The Sham al-Islami boys reminded Sami of a football team. They were incredibly relaxed, jumping up and down, loosening up as if it was some sort of pre-match routine. It seemed as if they would just dodge and weave between the bullets like Keanu Reeves in The Matrix. The most disorganized battalion was Liwa Tawheed, consisting mostly of Syrians. Sami had been asked to be present for the photo opportunity and filming of the beginning of the operation. He was meant to film the declaration, full of bombast, rhetorical flourishes and so forth.

In the evening Sami turned up at the derelict little factory warehouse with a flimsy tripod and a small handheld camera. There, all the men were sitting in a large carpeted room with a furious diesel stove burning and teapots boiling. He yawned and rubbed his eyes, wanting to get this over and done with quickly. But he knew looking at the twenty or so men sitting and leaning against the flaky wall whispering to each other that this would be a long night.

"Ahlan! Sami! Shoo akhbarak?" said a stocky, powerfully built man, giving Sami a warm smile. Radio bade Sami to sit down. Abbas, who was pouring everyone some tea, handed Sami a small cup of red tea. Although there were twenty men in the room, only three or four were talking. And these men sat over a large map of the area.

"What's wrong with calling the attack Operation Tawheed?" said Saleh, a prematurely balding Syrian and leader of Liwa Tawheed. "It tells the whole world what we all stand for and that we are all united in God's oneness."

"Well," said one, "because it implies that the operation's participants all belong to Liwa Tawheed and that isn't right."

"How about Operation Nusra?" said Radio, giving Abu Shaheed, the leader of Nusra, a sly glance as if he was soliciting his support. "We all want victory." He was right, of course; the word "Nusra" means victory in Arabic.

"Yes," replied Saleh, finishing his cup of tea and placing it down, "but then we have the same problem; people will think that only Nusra did this. Unity is a higher ideal than merely victory."

He had a point.

"Yes, yes you are right," said Radio diplomatically, "it is. But I think most people won't understand the concept; you know that the unity of God is hard to grasp. Think about it, what does Tawheed mean to the outside world who are still grappling with the trinity and all such polytheisms? All men understand 'victory'—it has a more universal acceptance."

"What's so hard about it?" said Talha, interrupting. The Iraqi said it with the politeness of a supermarket assistant working on New Year's Eve. "Ask a farmer who's been shoveling shit all his life if he gets unity and he'll get it. Ask him about the oneness of God and you'll hear the testimony of faith immediately. What's so hard about it? I'm not here to pander to how the rest of the world sees us. I care about Muslims; they understand the oneness of God instinctively."

It got a few titters from the others, especially from Anis, who had been lurking at the back watching the group. He seemed to be making his laugh more pronounced than the others were. So much so that Radio turned his head towards him to see who it was.

"Hmm," said Radio philosophically, "you know unity of God can be divided into three parts. No, no," he said, dismissing the name with his hand, "I just don't like it; it doesn't have a nice ring to it."

"You don't like the word that talks about the unity of God?" said Talha in a tone which accused him of committing near blasphemy.

One of the Emirs, Abu Ahmed, clapped his hands.

"Brothers," he said with an impatient tone, "can we focus?" He pointed to the map sprawled across the floor. "We still haven't properly planned this operation; let us not get hung up over a name."

"Right! That's decided then,' said Talha, clapping his hands as if it was final. "Let's plan this Operation Tawheed of ours, yalla Radio."

"Yes," Radio said, glaring at Talha, "I have a plan for Operation Nusra."

"Right," said Abu Ahmed, "stop this childishness! We'll call it Operation One Heart, okay?!" He turned to Saleh, who considered it carefully whilst studying the face of Radio in case it could be perceived as a victory by him. Radio looked at Saleh and Talha to see whether it could be seen as a victory for the two others.

"Well? Can we move on?" pressed Abu Ahmed.

All the men nodded and focused their attention on the map. As they began, Talha added, "Well, you know I was going to suggest it because one heart epitomizes the oneness of God doesn't it?"

Radio let it go. But he didn't forget. As they discussed the plan there was further sniping between the Emirs. Sami excused himself and left. There would be no filming that night.

Eventually the Emirs thrashed out the plan. Saleh's Liwa Tawheed would bring three tanks, and Abu Shaheed's Nusra would bring five Doshkas as well as two tanks. Abu Ahmed would lead the attack after the six PKC points had been taken out by the Liwa Tawheed fighters. He would then secure the entrance to the hospital and the rest of them would follow. That, at least, was the plan.

On the eve of the attack the regime gave the rebels the biggest barrage of barrel bombs that Sami had ever experienced. They knew the attack was coming. He couldn't get a wink of sleep. There were moments when he was sitting inside a room of an abandoned factory on the south side of the hospital when he was seized by this immense primeval urge to curl up and return to his mother's womb, just waiting for the barrel to fall and deliver his end. The reinforced concrete roof would not bear the weight of the barrels. As they tumbled in the air, they made that mad BOOOW WOOOW WOOOW WOOOW WOOOW noise that seized him with terror. They landed so close that he made his peace with his Lord plenty of times during the night and just closed his eyes. And all the time he heard the desperate yells urging the gunners to get the barrels or the chopper or both. And then, when the barrels missed the intended target, Sami prayed for the clouds to come in and cover the days and nights with fog and darkness so no more barrels would fall. The only person who didn't seem to feel that way was Radio—it wasn't that he was showing off; he must have been born that way. Even the bravest fighters curled up like babies when they felt the noise of a barrel come that close. But Radio just kept on drinking his tea and refilling the empty or near-empty glasses, quietly supplicating to himself. It gave the men around him a degree of calmness.

The attack didn't start on time the next day. Usually operations started after the Fajr prayer, at dawn, so the rebels could solicit the blessings of God on the operation.

But it was as if the whole operation had overslept on account of the barrel bombs falling the night before. When the men and materiel eventually mustered in the cold grey light of day, they came up short. Saleh's men, instead of bringing three tanks, brought only one. The Nusra boys brought one Doshka instead of the five they had promised. The men posted to ambush the retreating enemy's escape route were still having breakfast. The Liwa Tawheed boys failed to take out the six points that would resist Abu Ahmed's initial assault. In fact, the PKC points—the most crucial gunnery posts which had to be taken out, unless one wanted to die for the hell of it—were not taken. The hospital building took hits for sure and the noise was tremendous but the scarring was superficial and looked worse than it really was.

Abbas and his men had mustered in one of the buildings. They had punched a hole through one of the walls for them to constantly monitor what was going on using binoculars and Abbas' radio. He prepared his fourteen men, including Sami, making sure their guns were all in working order. By eleven o'clock the PKC guns had still not been taken out.

Abbas cursed quietly. "Why," he asked impatiently on the walkie talkie, "haven't the PKC guns been taken out? Why haven't the PKC guns been taken out? Over."

He did not receive a positive reply.

Instead Talha ordered him and his men to move in and attack the hospital entrance. Sami moved forward, waiting to obey the order, but Abbas halted him. "Wait here. Wait."

Despite Talha's order being repeated constantly, Abbas did not move from his place. When Abbas didn't reply, Talha's voice could be heard on the radio asking him why he hadn't started his attack. But Abbas ignored the order.

"What's going on?" Sami asked. "Why aren't we attacking? Why are we still sitting around here?"

"Brothers," said Abbas, "we are not going in unless those points are taken out because a hundred meters away is certain death—it will be for nothing. Let's retreat. Whoever hasn't slept could get some sleep. This isn't the way to fight a war."

One of the men, a young Egyptian perhaps no more than nineteen, pleaded, "Come on, let's just check if there's a way we can attack."

Sami concurred. "We should at least try, shouldn't we?"

"Why are you guys so eager to die for nothing?" Abbas said, shaking his head.

"Then at least tell the Emir!" Sami said, annoyed at the walkie talkie going off every few minutes. The voice was irate and angry.

"You are right," said Abbas, and he responded to the Emir bluntly. "Talha," he said, "I am not taking my boys on a suicide mission until the points have been taken out. Until then we are going to get some sleep. Over."

A blur of swear words followed. But Abbas did not respond. The conversation was over. They returned to Sheikh Najjar to recuperate and, in a house alongside other men, to drink tea and wait, listening to the snipers conducting their own grudge match with their opposing counterparts. They heard their exchanges in the distance, but apart from the odd fazdika and the mortars sounding off it was a relatively quiet day for Abbas and his men. [1]

In the evening, a Mitsubishi Pajero pulled up to the quarters. The door was slammed angrily shut. Talha strode in like he owned the place, and as soon as he entered he started to bark at Abbas.

"Why didn't you carry out the attack?" The huge Iraqi looked grim in his black hat and military camouflage.

"You are not the Emir," Abbas replied firmly. He didn't fear this looming figure—Radio was the overall Emir.

Talha shouted, "I am the operational Emir. What I say goes!"

"If you want to attack you can do it but I am following the plan that was outlined by our Emir," Abbas said nonchalantly, putting emphasis on "our," meaning Radio. "I'm not taking good fighting men to their deaths just because you say so."

"Didn't you come here for Jihad?"

"So?!" Abbas replied. "I am not going to throw fourteen lives away on a suicide mission. You may not have any but they have mothers and fathers."

It was a nice little snipe at Talha's pedigree and the Iraqi felt it for sure.

"I don't care how many lives get lost," said the Iraqi angrily, pushing his weight around. He looked like he was on a Baghdad street arguing with a taxi driver. "They will get martyrdom and they will get their reward!"

Abbas was unmoved by his aggressive gestures. He kept on stroking his beard which infuriated Talha even more.

"You can get martyred," replied Abbas. "I pray that you are soon." There was laughter from his boys. "I am not taking my boys until those points are taken out. Do you understand?"

Talha started to swear, curse and froth at the mouth.

"You finished?" Abbas asked. He turned to his men and told them to get up and follow him out to another location away from Talha, who continued to glare at him.

After they had found a new location to spend the night, Abbas made sure that all the men had eaten and were nice and warm. He also called Radio and notified him of Talha's behavior. It resulted in Talha receiving numerous phone calls from seniors reprimanding him. Radio and several members of the Shura council went down to Talha's headquarters. No niceties or pleasantries were exchanged as they studied the ordnance map of the district.

"I've noticed a weak point in one of the entrances," Radio said, pointing to the map. "You will attack it when the guards change their shift."

Talha showed Radio the weaknesses of his plan but Radio, as if to reassert his authority, replied, "The risk is acceptable. It's the best idea we have had so far."

"Very well," said Talha; he couldn't argue with him in front of the executive Shura council.

"It will only work," said Radio, "if your men give our boys covering fire as a distraction. I will ask Abbas to lead the attack personally."

"Can you do it now? I am having trouble getting through to him."

Radio called Abbas and gave him the instructions.

Abbas and his men awoke to the shrill, high-pitched sound of an enemy fazdika. It kept the unit on edge for the whole day. At least with tank shells or mortars there was a warning. The first bang was the launch of the projectile and then the elegant whirr followed; this allowed one to gauge where it would fall. If you heard the explosion that meant you were alive; not so with fazdikas. There were no signs of tiredness in the men. The shrill noise of the fazdika had scared tiredness and slumber away. All that was left was a bitter anger towards the hospital that stood there like a stubborn wart. It didn't matter what you threw at it; it just wouldn't cave in and brazenly kept on returning fire.

Abbas had been thinking about the operation all night—it wasn't a bad idea. By afternoon, he had ordered several of his men to bring the large guns as close as possible to the entry point, drawing heavy fire from the guards. Then three fighters from the Sham al-Islami battalion did the usual pre-match warm up, checking their guns and loosening up their limbs, and off they went towards the hospital. The three men headed towards a big rock under heavy enemy fire as if it was a stroll in the park. Once they reached the block of concrete they rested whilst the bullets bounced off it. The first fighter, a Moroccan, just casually stuck his head out to take a look. He signaled and moved forward. Abbas could hear the TAK TAK TAK and he prayed that they would make it to the next rock. And they did. Abbas shook his head in disbelief. "Nutters!" he said to himself. But seventeen meters on and the Moroccans were cut down by enemy fire. Only the first one was alive, but he was injured; he screamed in agony and held his stomach in pain. The enemy left him there waiting for someone to try to retrieve him; he was the worm—the bait. That is when Abbas remembered.

"Where is the distracting covering fire?" Abbas shouted down the wireless whilst watching everything on his small binoculars. "Talha! Where is it?! Are you trying to get us killed?" There was no response. Abbas used so many expletives about Talha's family that even as the Moroccan fighter was bleeding to death some of the men couldn't help but laugh.

A young Egyptian was killed as he took the bait to retrieve him. He went against Abbas' orders. Abbas and his men stayed with them till their last even though they did not venture out to retrieve their bodies.

[1] "Fazdika," in Syrian colloquial Arabic, refers to the shells fired by a 2S1 Gvozdika, a Russian-made 122mm self-propelled howitzer.