Frederick Deknatel is the Executive Editor of Democracy in Exile, the DAWN journal.

عربي

Amid the U.S. evacuation from Afghanistan in late August, one organization working overtime to get vulnerable Afghans out of the country was the Artistic Freedom Initiative, which provides pro bono legal representation and resettlement assistance to artists facing persecution, censorship and other threats around the world. The New York-based organization was "in triage mode" as the withdrawal deadline neared in Kabul, as AFI's co-executive director, Ashley Tucker, told me, having "received hundreds of requests for assistance" from Afghan artists. Since then, AFI has helped many of them apply for visas and resettlement in the United States.

"We have not faced a humanitarian crisis like this thus far in the existence of our organization," Tucker said. Since its inception in 2017, AFI has handled the cases of more than 400 at-risk artists, the majority of them from the Middle East and North Africa—helping them navigate the visa and refugee resettlement process, and supporting them with housing and other needs in their new home. But Afghanistan was on another scale. AFI was "receiving hundreds of requests from artists in one single country," which Tucker said had never happened before. The applications they received included practically every kind of artist, including many musicians, she added, "since the Taliban has now banned music again." AFI was also contacted by Afghan journalists and photographers hoping to escape Kabul and the prospect of having to report and work under the Taliban.

"Traditionally, AFI doesn't necessarily take on cases of journalists, because there are already a number of organizations out there that are designed to support journalists at risk specifically, and there are less in the way of support for other forms of the arts," Tucker said. "But in this case, we are just welcoming as many people as we can to apply." It sounded like even more of an indictment of the situation in Afghanistan with the exit of American forces and the collapse of the Afghan government: Essentially everyone was trying to get out.

Tucker previously worked for the United Nations Human Rights Committee in Geneva, the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, the Centre for Civil and Political Rights, and PEN America's Artists at Risk Connection. She has worked on strategic litigation before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and conducted research and human rights trainings in Haiti. She is also a member of the New York State Bar Association's Committee on Immigration Representation.

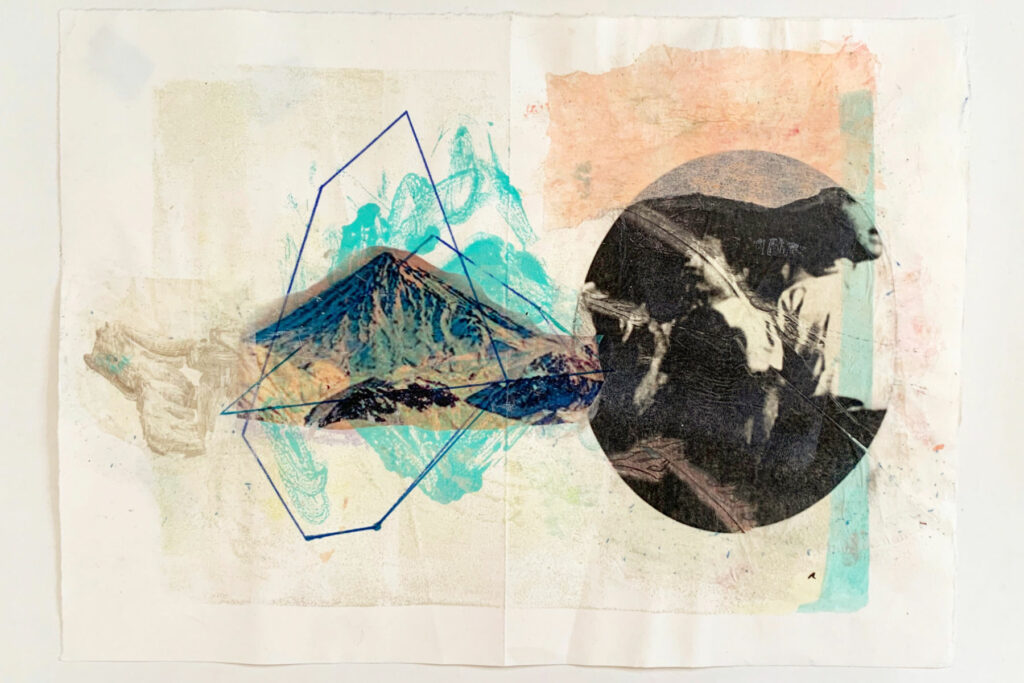

In an interview with Democracy in Exile, Tucker compared the plight of Afghan artists with other at-risk artists in the Middle East and North Africa supported by AFI in recent years. Photos and profiles of several of those artists accompany the interview. DAWN's executive director, Sarah Leah Whitson, also serves on AFI's Advisory Board.

The following transcript has been edited lightly for clarity and length.

Have there been certain countries or certain types of artists or profiles that have made up more of AFI's resettlement work?

I would say with each year, we receive an increasingly diverse number of requests of artists from different countries. But by and large, over the last four years and change, the majority of the requests have come from artists from the Middle East and North Africa—which is not a surprise. But increasingly, we are getting requests from folks in Latin America, also in other parts of Africa, certainly some countries in Asia, and even in Russia and Georgia, for example. In terms of discipline, our artists work across over 30 creative disciplines. Again, we try to construe broadly the definition of artist when we are working in this context and within these parameters, but I have noted that within the last year or so, we have definitely received an increased number of requests from filmmakers specifically. We're doing our best to find new ways to try to accommodate that, because that has not made up a large number of the requests in recent history.

In the Middle East and North Africa, has there been a trend of more artists, for example in Egypt, trying to leave, with the situation under Abdel Fattah al-Sisi's regime getting more and more repressive? Or, for example, in the United Arab Emirates or Saudi Arabia, where there are growing crackdowns on all kinds of civil society? Have you seen connections to the broader political trends?

I think I can safely say that, not the majority, but a very fair number of the requests we're receiving from the MENA region tend to come from Iran and from Egypt. And right now, we're seeing a lot of artists who have fled Iran to Turkey and are now looking for assistance to relocate from Turkey to the United States or elsewhere. There is a shocking number of Iranian artists who have fled to Turkey.

In terms of AFI's mission is resettling and providing assistance and housing to artists, is it trying to fill a vacuum left by bigger refugee resettlement organizations? Or is it also that artists are particularly at risk and therefore need organizations like AFI advocating more directly for them?

I think the two things you mention are inextricably tied together. Initially, when AFI was conceived, it was primarily as lawyers to offer this immigration representation to at-risk artists. But once we started working, we very quickly realized that these artists were coming to us with other needs outside their legal status, and in many ways, helping them to stabilize their legal status opens the door to new questions, new needs, new vulnerabilities—like, where am I going to live now that I can stay here? I don't have a roof over my head, or I've been staying with friends for the last month. I can't keep doing this forever. Where can I go? Also, I left my community behind, unexpectedly and suddenly. And when I say community, I mean family, I mean a professional network, I mean creative colleagues—everything, left behind. How can I start to work again as an artist? Where can I find connections to start building a new community, whether that's among the creative community in New York, or the diaspora community, or both?

Because these artists didn't seem to have anywhere else to go, though they knew that we were the attorneys working on their legal case, they still came to us with these concerns. And it is truly from those early stages that we quickly expanded our work to include the Resettlement Assistance program, which focuses on work authorizations for the artists, helping to connect them with grants and fellowships, and then co-designing and launching the Residency program specifically for at-risk artists that provides housing, professional development, community engagement and legal services. This is a holistic approach to offering support to meet the very complex and intersecting needs of artists at risk that are simply not being addressed elsewhere.

And then finally our third program, Artists for Social Change, is a program to create platforms for the artists to showcase their work, and to help keep them connected to the causes that they were dedicated to at home. And that program itself ties right back to the legal services, because in stabilizing artists' legal statuses, we need to be able to create work for them to show the government that they are working here, that they've been invited here for this or that thing. So, they are symbiotic, all of these programs, and there are many, many artists in our network who have benefited from all three of our programs. They often will enter through the legal services, go through resettlement and then take part in our Artists for Social Change program. We've designed it that way, but it was from learning step-by-step in the early stages of our inception.

Generally, have you found, for example in New York, that artists who have been resettled there and have gone through these programs have been able to reestablish themselves in a new community, despite all the adversity they've faced? Or is there always that tension of being an artist in exile or in the diaspora?

I don't think those things are mutually exclusive. I think there's a bit of both. But I'm very proud to say that we recently did a legal impact assessment for a number of artists in our network who received our pro-bono legal services. And we were able to determine that a cross section of 15 of those artists who received that pro-bono immigration representation from us went on then to achieve a total of 320 individual creative accomplishments, whether that was showing their work at an exhibition, putting on a concert, doing a reading or publishing something. Obviously there are many factors involved, but having been able to stabilize their legal status and give them the ability to work legally in the United States, this helps to facilitate their creative work as well. And, again, doing everything we can to help connect to these communities once they're here.

But there is always a struggle with these artists to be seen as artists first and not as "at-risk" first, and people have an interest in the work of exiled artists and things that they're thinking about and exploring through their work and creative process. There is a tension there between what it is that they're doing and want to be doing, and also the way they are seen. We understand that and try to be very sensitive to it, too, as we go through the resettlement and professional development processes with them.

—To be seen as an artist first and foremost, not a refugee artist or an artist in exile.

Exactly. There are some who embrace that and who are exploring these issues in their work, but there are many others who understandably are not interested in being seen or in perceiving themselves that way.

In aiding and protecting these artists, can you also help preserve culture that is at risk of being lost, whether it's Iraqi culture or Iranian culture, for example?

Increasingly in our public programs, exhibitions and festivals, we are incorporating the work of artists whose medium or discipline has been listed on, for example, UNESCO's list of intangible cultural heritage that is in need of safeguarding. So, increasingly AFI is moving into spaces where we're working to safeguard and champion not only artists at risk individually, but art at risk as well. And these things are totally tied up together. One example that comes to mind is an artist from Iraq, Hamid al-Saadi, who is the grand master of the Iraqi maqam. In bringing him out of Iraq and to the United States, we have in many ways contributed to the continued flourishing of this form of art. He is the foremost performer of the maqam in the world and can recite all of the variations from memory, which is extraordinary. So, yes, absolutely—we feel that our work with individual artists at risk is also tied up very closely to safeguarding culture at risk as well.

Refugee admissions to the U.S. were cut dramatically for four years under Donald Trump, and they've been brought back up under Joe Biden. There was pushback when the Biden administration initially was not going to raise the level back to where most people expected it to go. Do you think that the Biden administration in general is doing enough to resettle refugees, including at-risk artists, and what more could they do?

It's still a bit early days in the Biden administration. Unfortunately, this crisis in Afghanistan has not done wonders for how we might perceive his administration to be handling refugee issues. However, AFI not long ago put together a series of policy recommendations for the Biden-Harris administration specifically on issues to do with artistic freedom and with cultural heritage preservation. It outlines very explicitly what we feel the administration could be doing to better safeguard artists at risk, and protect the arts in general, both in the U.S. and abroad. We address issues of funding and recognition for the arts, alongside specific recommendations to do with immigration policy as well and changes that they could make that would better facilitate the movement of artists across borders and resettlement to the United States, whether temporary or permanent.

I would just add that while we've talked about AFI's programs—the legal services, the resettlement, and our Artists for Social Change program—these are all tangible services that we're offering to the artists. They are direct services, which we've come to learn are very much needed across the board for this community of people who are at risk. But part of the underlying ethos and mission of the organization is that while these direct services are critical, they are also advocacy themselves. And we are interested in continuing to push further into a more traditional advocacy space, in addition to continuing our direct services.

At the moment, we are working on releasing a series of human rights reports that analyze the state of artistic freedom in various countries around the world. We are also hoping to move into a space where we can utilize some of this research and reporting for purposes of advocacy at the international level. While we have reached out to the Biden-Harris administration, we are also interested in helping to make an impact at the regional and international level, especially in countries where many of our artists are coming from, so that we are helping to create positive change in these countries of origin and not just here in the United States.

*

Main photo: Iranian musician King Raam performs at the Brooklyn Music School in November 2019. Raam's piece, "Departure," was developed during his residency in the Safe Haven Incubator for Musicians NYC (SHIM:NYC), an artist-at-risk residency program recently launched by AFI and Tamizdat. Photo by Jonathan McPhail.

Raam started his musical career as the founder of Hypernova, a post-punk band born in the Tehran underground of the early 2000s. A politically active singer, he joined protests and wrote songs that spoke out against the Iranian government.

In January 2018, Raam's father, Kavous Seyed-Emami, a prominent Iranian-Canadian professor and environmentalist, was arrested in Tehran under false charges of espionage. Two weeks after his arrest, he died under suspicious circumstances in Iran's notorious Evin Prison. Raam and his family attempted to flee Iran, but Iranian authorities detained his mother and confiscated her passport. Raam and his brother were allowed to leave the country, but his mother was detained for 582 days before finally reuniting with them in Canada.

![Security forces loyal to the interim Syrian government stand guard at a checkpoint previously held by supporters of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, in the town of Hmeimim, in the coastal province of Latakia, on March 11, 2025. Syria's new authorities announced on March 10, the end of an operation against loyalists of deposed president Bashar al-Assad, after a war monitor reported more than 1,000 civilians killed in the worst violence since his overthrow. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said the overwhelming majority of the 1,068 civilians killed since March 6, were members of the Alawite minority who were executed by the security forces or allied groups. (Photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR / AFP) / “The erroneous mention[s] appearing in the metadata of this photo by OMAR HAJ KADOUR has been modified in AFP systems in the following manner: [Hmeimim] instead of [Ayn Shiqaq]. Please immediately remove the erroneous mention[s] from all your online services and delete it (them) from your servers. If you have been authorized by AFP to distribute it (them) to third parties, please ensure that the same actions are carried out by them. Failure to promptly comply with these instructions will entail liability on your part for any continued or post notification usage. Therefore we thank you very much for all your attention and prompt action. We are sorry for the inconvenience this notification may cause and remain at your disposal for any further information you may require.”](https://dawnmena.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/syria-22039885951-360x180.jpg)