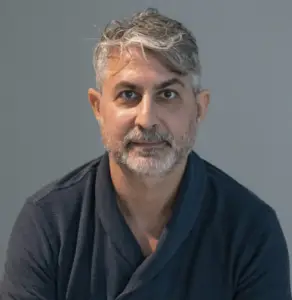

Omid Memarian, a journalist, analyst and recipient of Human Rights Watch's Human Rights Defender Award, is the Director of Communications at DAWN.

Twenty-two years after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the biggest threat to the United States is not al-Qaeda or another foreign terrorist group, but domestic terrorism, says writer and journalist Lawrence Wright, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11. "The present enemy, as far as the United States is concerned, is domestic terrorism," Wright tells Democracy in Exile in an extensive interview. "And what has happened is that the domestic terrorists are copying al-Qaeda. Look at The Base," the militant neo-Nazi and white supremacist group that emerged in the U.S. in 2018, "which is what al-Qaeda means in Arabic. They're deliberately not hiding the tribute that they are paying to al-Qaeda and other terrorist organizations of past and present. This is our biggest problem—domestic terrorists, our own people."

Wright, a longtime staff writer at The New Yorker and a fellow at the Center on Law and Security at New York University School of Law, is a prolific author, screenwriter and playwright. In 2003, he spent time in Saudi Arabia mentoring young reporters at the Saudi Gazette, an English-language newspaper in Jeddah. It was there that he met Jamal Khashoggi, who at the time was the deputy editor of another Saudi paper, the Arab News, and, as Wright recalls, "a magnet for foreign journalists like me because he wasn't afraid to analyze the situation." They were friends for the next 15 years, until Khashoggi's brutal murder at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul.

"Jamal was a wonderful personality and a brave man," Wright says, reflecting on the upcoming five-year anniversary of Khashoggi's killing on Oct. 2. "One thing I've learned from spending a lot of time in tyrannical societies is that dictators create cowards. People are afraid to speak up for good reason. Jamal was not afraid. And that really set him apart."

Wright also discusses the legacy of America's long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, calling the invasion of Iraq "one of the greatest diplomatic blunders in world history." He describes Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman as "walking in the footsteps of Vladimir Putin." And he details his visit to Hebron in the occupied West Bank earlier this year, where an Israeli soldier beat prominent Palestinian activist Issa Amro directly in front of Wright and another journalist, who filmed it.

The Biden administration's effort to secure a normalization agreement between Saudi Arabia and Israel, he says, "comes at a time when Israel is devolving into maybe what it was always going to be: a one-state entity, that is, a Jewish entity from the sea to the Jordan River." As he warns, "There will have to be a reckoning with the change in Israel and its demography, and what appears to be just continuing ethnic cleansing of the West Bank."

The following transcript has been edited lightly for clarity and length.

"Al-Qaeda aren't a present enemy in the way that they were. The present enemy, as far as the United States is concerned, is domestic terrorism."

- Lawrence Wright

In your book The Looming Tower, you provided a compelling look into al-Qaeda and the origins of 9/11, drawing in part from your experience in Afghanistan in 2003. Considering the recent U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, how do you anticipate it will be remembered historically? And what degree of responsibility and discredit do you believe President Biden will bear for the manner in which the withdrawal was executed?

Lawrence Wright: The U.S. has had a history of invading countries—and then having to leave them in dishonor. Vietnam is a good example; Iraq and Afghanistan. I don't know when our country is going to learn its lesson that it's best not to get in, in the first place. I don't oppose the idea of going into Afghanistan at the beginning, in order to root out al-Qaeda. But then deciding to make the Taliban our enemy was a huge mistake. The Taliban was incompetent, ignorant, ridiculous and corrupt. There were a lot of problems with it. It's a terrible entity to govern any country. But it was not America's enemy at the time. It was just an incompetent entity that was protecting al-Qaeda. But whether they protected them or not, we rooted them out. As far as I was concerned, the job was done.

You can't talk about the withdrawal from Afghanistan without going back to the Trump administration, which negotiated the terms. So essentially, Biden was following the Trump agenda. And you also have to admit, even the Taliban didn't know they were going to be able to walk into Kabul without any resistance. Nobody really understood what was going to happen. There were all these people saying that we should just keep a force there. Imagine a small garrison of American troops surrounded by the Taliban. How long is that going to last? There was a series of catastrophes that led to what happened with our withdrawal, but it was predictable from the moment we decided, once we had rooted out the al-Qaeda, that the Taliban was next.

How could the Biden administration have done it differently?

If they'd had more protection at Kabul Airport, where they were evacuating Americans and supporters of America, it might have made a difference. It's hard to look back at history and say how would it be different. I think you choose which point in history to say, how would it be different from here? And the point I choose is, how would it be different from the moment they decided to turn on the Taliban? I think everything kind of followed from that.

How could the U.S. make friends with the Taliban at the time? They trained al-Qaeda and the group was embedded within the Taliban. How would it have been possible for the U.S. at the time to keep them as a player in the game?

I'm not advocating that we would make friends with the Taliban. It would be somewhat like the situation we have now. We have nothing to do with them, although we are providing aid, food aid and stuff like that. I think that's perfectly legitimate. But like Cuba, we've been not friends with Cuba for longer than you've been alive. And it's perfectly possible to have a standoff relationship with a corrupt regime like the Taliban.

Looking at the return of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the proliferation of regional extremist groups in the Middle East, some with backing from the Islamic Republic of Iran, and the continued involvement of various regional powers in conflicts such as those in Syria, Iraq and Yemen, what is your perspective on the future of the "war on terror"? In what ways have circumstances evolved since 2001?

Well, al-Qaeda has been quieted, essentially. It still exists in certainly a larger organization than it was on 9/11. And still, its goals haven't changed. But they aren't a present enemy in the way that they were. The present enemy, as far as the United States is concerned, is domestic terrorism. It far outranks any kind of foreign terrorism that we're experiencing within our shores. And what has happened is that the domestic terrorists are copying al-Qaeda. Look at The Base [the militant neo-Nazi, white supremacist group in the United States], which is what al-Qaeda means in Arabic. They're deliberately not hiding the tribute that they are paying to al-Qaeda and other terrorist organizations of past and present. This is our biggest problem—domestic terrorists, our own people.

Then we look out at the rest of the world, and terrorism tends to arise in chaotic situations, and we have a lot of chaos. From my point of view, the biggest threat in a foreign terrorist arena is the number of refugees in the world.

But al-Qaeda or the Islamic State didn't have roots in refugees, as their cause was very much separate from the refugee problem. For instance, when it comes to Iran and militias like the Hashd Alshaabi and similar pro-Iran groups, they are used in the Iranian regime's fight against the U.S. in Iraq and other countries in the Middle East. These groups act as a tool of foreign policy for Iran and represent a different type of threat.

That's true. They are state-sponsored groups. And, in a way, I see this problem as being easier, because Iran could turn off the switch at any point and essentially, these groups would die on the vine. Without Iranian support, I don't think that they would exist. Reconciliation with the Sunni world, especially Saudi Arabia, would go a long way towards achieving that. State-sponsored terrorism is an immense threat, and one of the reasons for that is the access to really dangerous weapons. But it's also a more solvable threat than what has devolved into a lot of lone wolf operators, leaderless resistance and that kind of thing, that's very hard to detect. Highly empowered individuals or small groups pose real threats. State-sponsored threats are more durable as long as the state is sponsoring it. But once that stops, then they can go away.

Anti-Americanism has become one of the pillars of the Islamic Republic and a part of the regime's fabric. How and why would Iran ever stop doing what it's doing now, using these groups as leverage in advancing its foreign policy regionally and globally?

Iran has to change internally and is in a very turbulent state. The leaders of Iran do not have the endorsement of the population, it's really clear. And historical paradoxes—like, how can they stay in power?—eventually get resolved, and this one will as well. They're not going to endure forever; they can't. They have an agenda that the people are against. The longer they're in power, the more people turn against them. So repression is increasing, and repression causes reaction. It's an equation that dictators all over the world have faced: The more you repress, the more angry people become, and the more you lose the support, and eventually, something happens, and the regime finds itself without any supporters. And I think that's the future of Iran.

Considering the nationwide protests that erupted in Iran last September, do you see any parallels between the challenges currently faced by the Islamic Republic and the circumstances that prevailed during the last years of the Shah's regime and led to his fall in 1979? Are there similarities suggesting that the Islamic Republic might find itself in a position akin to that of the Shah's regime in those pivotal years?

That's an interesting question to ask, Omid, because the way I look at the Shah, and how he lost the support of his people, is that he tried to change things too quickly. His goal was to turn Iran into Italy within a generation. And he attacked a traditional foundation of the society and made a lot of consequential decisions that, from his point of view, were steps along the way of creating a modern society. And the traditionalist forces reacted. I don't think the majority of Iranian people wanted the Ayatollah to come in and rule, but the repression under the Shah had caused an immense backlash among the Iranian people. You would know this better than I.

The paradox that I'm talking about is that rulers, especially absolute rulers like the Shah, may have in mind a noble goal. Let's become Italy—that would be an interesting development. But, along the way, they don't get the permission of the people to move that quickly or in that direction. So they lose the support.

Tyrants, like the people that are governing Iran right now, want to pull the country in a direction that they favor. And the actual result of that is they create an angry, increasingly secularized population that wants to get rid of them. This is what they've wrought. They haven't created the ideal Islamic Republic by any means. They've forced something on the people, and people don't like to be forced. One can say that in Palestine, Israel has succeeded in suppressing the Palestinian people. But there are long-term consequences. They're going to come out on both sides.

On American domestic terrorism, how much of the polarization that we are seeing now might be rooted in the two wars that the U.S. launched in Iraq and Afghanistan—given the cost of those wars, and polarized conversations around freedoms and national security?

Well, start with the fact that the invasion of Iraq was one of the greatest diplomatic blunders in world history. It's hard to find parallels, because Iraq was not the problem. And so, it's an enduring tragedy. But honestly, I don't think it plays out in American politics as greatly as you might think.

I think everybody wants to walk past that, and decades have passed. Iraq is, one would not say, a stable democracy. But it gets to the question. And my feeling is that the way that it resonates in American politics right now, at this very moment, as we're moving into another presidential cycle, is where should America's efforts be in the world? And there's a side of the Republican Party that's very isolationist. Donald Trump, Ron DeSantis, are exemplars of that. I think that the example of Iraq, the example of the withdrawal from Afghanistan, feed their argument. It could also be that they have other motives, mainly that they don't believe in democracy.

The George W. Bush administration had a policy of trying to democratize the Arab world. That's not an easy thing to do, as your organization probably has learned. It's hard to plant the seeds of democracy in the Arab world and have it grow into a thriving, prosperous entity. But that idea has wilted, I would say, in both parties. The Biden administration is still very much of the view that America has a role in spreading democracy in the world. But it's not very active in that.

How about democracy at home? With the rise in populism and the presence of far-right groups that don't shy away from intervening in democratic processes, particularly a year before another consequential elections?

We're coming to a decisive point, early next year, when Trump will go on trial and the primaries are going to happen. At this point, it seems like he's got the nomination clinched. So here are the forces at play there. It is democracy the way that Trump is riding. He's asking for people's votes. He's not trying to overturn the election at this point, although he might try if he loses, again. But his supporters are going to feel incredibly disenfranchised if he's locked up and held apart from the presidential nomination. Or suppose he wins the nomination and is in prison. The sparks are out there to start something that would be like a civil war.

"If you're wondering about the future of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, he seems to be walking in the footsteps of Vladimir Putin."

- Lawrence Wright

Biden had said that he would make a pariah of Saudi Arabia before he came into office, but in the past three years, there appears to have been a shift in Washington's stance towards the kingdom. Critics argue that the Biden administration has, in fact, gone to great lengths to accommodate Saudi interests, at the expense of human rights and democratic principles. However, it seems that this has not yielded significant results for the U.S. so far. What, in your assessment, might be the repercussions of the Biden administration's policy approach toward Saudi Arabia?

Well, I worry a lot about Saudi Arabia. And I think sometimes, if you're wondering about the future of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, he seems to be walking in the footsteps of Vladimir Putin, and he has massive amount of wealth on his hands. So, he's a dangerous entity. Speaking as a person who was a friend of Jamal Khashoggi, the idea of justice—it's just not present.

We have to adjust to a world in which, as with Russia, you have hooligans or criminal elements that are in charge. And in the case of MBS, one has to admit he's a visionary leader in a country that has never had one. Jamal and I had this in our last discussion. I didn't understand MBS in the way that he did. To me, he was a reformer that Saudi Arabia badly needed—and I still feel that way. I think many of his reforms are great. But on the other hand, he's prone to highly irrational actions, like kidnapping the Lebanese prime minister, like starting a war in Yemen that he didn't need to, or that absurd thing with trying to eliminate Qatar as an independent entity. I could go on and on, about the massive number of people rounded up and put in the Ritz-Carlton, and one was killed. Just shake them down—that turns out to have been a very popular action in Saudi Arabia.

But all of this is evidence that this is a person who doesn't acknowledge any kind of limitations and is prone to making freshman mistakes. Maybe he's learned a little bit in his tenure in office. He's still a young man. He's going to be there for a long time. And so we have to adjust to the fact that Saudi Arabia is a powerful country, and made more powerful by MBS. And if we want to participate in helping to shape the future of Saudi Arabia, we have to have a relationship with it.

It's a difficult marriage. Saudi Arabia is, in many respects, a creature of American foreign policy. And it has been a great success. But now, that creature is off the operating table and walking on his own. And we don't have very much control over the future of Saudi Arabia, and nor should we control any country. But we need to have alliances and relationships that are productive for us and for the citizens of those countries. It's a tricky equation in Saudi Arabia right now.

Is Saudi Arabia a reliable ally for the United States, like Japan or South Korea? Because the way the U.S. is treating Saudi Arabia is like an ally, especially if the U.S. agrees to provide security guarantees for the kingdom the way it does its NATO allies.

The examples you cite are not really good examples, because Saudi Arabia is not like Japan or South Korea. Both of those countries have democracy at the base of their political system. There's no democracy in Saudi Arabia. I remember when I was living in Jeddah, and I was mentoring these young reporters at the Saudi Gazette, and one of my female reporters, I asked her, what was her ambition? And she said, I want to be a politician. And I said, how would you do that in a country that has no political system?

That's just a very small example of how the aspirations of ordinary Saudi citizens are choked off by the fact that they live in a tyrannical society. It's a far more progressive society than it was when I was living there in 2003. And it's made a lot of advances. And most of them have been at the urging of MBS. So, it's a complicated scenario. I think we all are looking at it, and I wish the Saudi people the best.

I think it would be up to his family, MBS's family, to make a change. But in the history of that family, there's never been a great reformer until MBS came along. So it's a very complicated question, and it's been heartbreaking for me not to see justice done in the case of Jamal Khashoggi, and it's upsetting to me to see that their threats against Saudi citizens living elsewhere continue. It's very dangerous. The idea that there would be a kind of Saudi dragnet to pick up any of the dissidents that might be out there and deal with them in the ways that they've shown that they will—that can't be tolerated.

Why did Jamal Khashoggi's murder have such a significant impact? What was unique about his murder, do you think?

He lived in America, had a green card, and worked for The Washington Post. He was not an American citizen, but he was under our auspices, in a way. But the other thing is, Jamal was a wonderful personality and a brave man. One thing I've learned from spending a lot of time in tyrannical societies is that dictators create cowards. People are afraid to speak up for good reason. Jamal was not afraid. And that really set him apart. That's one of the reasons when I was there and went to see him, he was a magnet for foreign journalists like me because he wasn't afraid to analyze the situation.

There were no doubt things that he didn't want to say. An example was when I had one of my reporters ask why there are all these sewage trucks in Jeddah. These brown Mercedes tankers would go around and empty the septic tanks. Every afternoon, there was a parade of these stinky trucks going through the streets. I asked one of my reporters, looks like there's a lot of sewage in the street. And so he found out that there were manhole covers in Jeddah. The sewage system looks like it was… there were just holes in the ground. There was nothing there. The guy delegated to create the sewage system in Jeddah took some money and built a mansion in San Francisco and another in Jeddah with a discotheque. That was where the money went, and nothing happened to him.

Jamal knew that story. Many people in Saudi Arabia knew that story but were not allowed to publish it. And they told me because I could publish it. Once it's been published internationally, then it becomes acknowledged in Saudi Arabia. The free press is something I really believe in, in every part of my being. So we started writing stories about it. Then we were told, by the way, there's a prince in charge of making a new sewage system—which was why no other newspaper in the kingdom had been writing about this—and we were directed to stop.

It was not just the sewage system and the trucks—the destination of those trucks was up the hill to this big lake of sewage. I mean, massive. And it was held together by a sand dam. Just a hole in the ground—and on top of an earthquake fault. So if a breach in the dam occurred, Jeddah would be buried under six feet of shit. It was like, the worst possible end to a thriving city. The story came about because the sewage truck drivers were being charged an extra rial to unload their sewage into the lake, and they couldn't afford it. So they went on strike, and that's why it came to our attention. Hepatitis and other diseases were also spreading.

This is an example of why we have a free press. And I will judge Saudi Arabia as a freer society when I feel like the press has been allowed to speak.

In such circumstances, what's your take on discussions about the U.S. providing security guarantees to the kingdom in return for Saudi-Israeli normalization?

Basically, I'm not in favor of America guaranteeing the safety of countries around the globe. It has worked, though; NATO is an amazing accomplishment. But NATO's not just America. It's a union of other democracies for mutual protection. But it's a high-risk thing [with Saudi Arabia] because you're forming an alliance with an irrational actor who's not accountable. That concerns me.

And is the payoff worth it? This is ostensibly a tradeoff for Saudi Arabia to recognize Israel. This comes at a time when Israel is devolving into maybe what it was always going to be: a one-state entity, that is, a Jewish entity from the sea to the Jordan River. Well, that's not America's program. There will have to be a reckoning with the change in Israel and its demography, and what appears to be just continuing ethnic cleansing of the West Bank. That has to come to a head at some point.

And are we willing, maybe, to make a deal between Saudi Arabia and Israel if there was a chance of granting the Palestinian people some kind of franchise, a right to exist without being controlled by the Israeli army? That would be an actual two-state solution or a one-state solution in which the Palestinians are fully invested as citizens? Neither one of those things seems likely to happen. And so, it reflects back on what we're trying to achieve with Saudi Arabia, because we want to have some influence with Israel, and we haven't exerted that recently.

Saudis and Emiratis have invested enormously in the U.S. economy in the past decade. Are there risks involved that they are buying influence in the U.S.?

It's good for Saudis to come to the U.S. and become more invested in American society. For one thing, it reflects back on their own country. They get to experience what freedom really is. As messy as it is, it may be horrifying right now, but it's what it looks like. And I don't oppose them buying property. I mean, we've dealt with this for years. Remember when Japan was the great threat, and they bought Rockefeller Center and stuff like that? That's all in the rearview mirror. America is an international marketplace, and that's what gives us strength.

But I do object to doing things like planting Saudi spies inside Twitter and vacuuming up all the messages that Saudi dissidents have exchanged. We can't endorse that. We have to find a way to operate these… we've never really figured out what social media is. It's not the press; it's something else, but it is an aspect of our society that's very dynamic. We want to keep those kinds of things. But when it's being used to threaten people, especially people who are fighting for democratic changes, then we have to step in and do something about that. If they want to buy Rockefeller Center, or Wall Street or whatever, that's a good investment. And the more good investments they make in America, the more they will want to have America be strong and resilient. They're not buying it to destroy America; they're buying it to hedge their bets in Saudi Arabia.

If the rest of the world is invested in America, they have a reason to want to see America as a stable entity. I think that's true, even of China. We are each other's major trading partners. The solutions to our economic problems, and theirs, largely lie in each other's countries. A brake that you put on, when things get heated up diplomatically, is that we need each other economically.

Let's speak about your trip to Hebron earlier this year in February. With all that is happening in Israel regarding the judicial overhaul and the protests, how do you describe the situation in Hebron and in Israel in general? What was the mood in the West Bank?

I was in Hebron not as a journalist, but as a novelist. I chose Hebron as the setting for the novel, because it's the most concentrated amount of hate I've ever seen—and I covered the civil rights movement in the U.S. In some respects, I felt a kinship to that, but it was far worse. I'm the same age as Israel. I'm 76. And in my lifetime, I've seen things change that will "never change." Apartheid in South Africa, the civil rights movement, the breakup of the Soviet Union, and the election of a Black president in the United States. These were things that were never going to happen, and they all happened in my lifetime. But the Israeli-Palestinian conflict hasn't changed a bit. And it is the most durable conflict on the globe.

What exactly happened in Hebron? You tweeted a video of the incident, which received many conflicting responses.

Yeah, it was horrible. I was with Issa [Amro], and a Belgian photographer [Barbara Debeuckelaere] who was with Issa, and he was giving me a tour of the Old City. He showed me his neighborhood. All the shops in the Old City are practically closed. His house still stands, but the doors have been welded shut. He showed me where the barbershop was, where his teacher lived, and so on.

We came to Al-Shuhada Street, and there's a long portion where Arabs are not allowed. So he said, you go ahead, and I'll meet you 100 yards up the way. He went into what was actually a Muslim cemetery. Barbara and I were walking up the street and there was an outpost with this one Israeli soldier. He was a very tall and powerful-looking young man. Although I knew it theoretically, one of the big surprises to me is how young these people are in the IDF. The soldiers, they're their high school kids. They just got out of school. They're 17, 18, 19 years old, way too young to be policing people. But anyway, here was one of these guys. And we nodded to him, and walked on by.

Then he caught up with us and started talking to us. The cemetery was elevated, and there was a wall. So Issa was walking along here, and he looked over the wall, and he saw this soldier questioning us, and he said, they're foreigners, they're Westerners, you have no right to. He was getting in the face of the Israeli soldier, and then the soldier said, okay, go on. But while Issa and the soldier had been talking, Barbara filmed it.

And the soldier had second thoughts. He catches up with her, and as we're coming to the end of the cemetery line, the soldiers says, delete that. Issa appears and says, you have no right to ask that. And he's totally right about this. So he comes down, and then the two of them are having this face-to-face confrontation, and Barbara is filming it. She had deleted the original video—as it turned out, it was in her trash, and she retrieved it later. But she filmed this confrontation between Issa and the soldier. And Issa is saying, call your commander, you think you're right, but you're wrong. He's very forthright about this, and the soldier did call. He says, we have some liberals here.

He hangs up the radio, and he and Issa have a few more words. And then he grabs Issa by the collar, drags him around, and puts him down on a bench. He's standing right in front of him, the soldier is, a very hostile situation, and I'm alarmed. I told Barbara to continue shooting. That was right across from the IDF barracks, where there were other soldiers. And I guess I'm going to negotiate. So I talked to the one soldier that seemed to be most in charge. I said this is getting out of hand, and he said I think you're right. I said, yeah, you've got to get between these guys. It became very clear to me the other soldiers were afraid of their own soldiers. He was a fearsome-looking guy.

And then something went off in his mind. He picked up Issa by the neck—he was a very strong guy—and he hurled him into the street. Issa's head missed the curb just by a fraction. I mean, he could easily have been killed by that. And then the soldier kicked him so hard that he almost fell.

Well, then, some of the soldiers start to come forward. And I thought it was really clear to me that this soldier wanted to finish the job. We were standing where just a month or so before—I'm not sure, maybe more than a month—a Palestinian had been killed in that very spot by an Israeli soldier, when he was lying on the ground, unconscious. This soldier just shot him in the head. And so the precedent was there. And I thought it was going to happen. It was happening in front of us, and we were filming it. It was bizarre.

Finally, the smallest person on the IDF side—he wasn't a soldier, he was dressed in a red sweatshirt—he was a little guy, but he actually started fending off the soldier. Issa was demanding medical attention, and they did bring out a guy who claimed to be a medic and said there was nothing wrong with him. We helped Issa back up the hill to his house.

I posted [on Twitter], and I said, one of the things that really disturbed me was the absence of humanity in the face of this Israeli soldier. Somehow that was taken as my expressing sympathy for the occupier. I don't understand that at all. I'm the guy that posted the videos. I showed what happened, and when the IDF issued a statement about the soldier responding to Issa being provocative and disobedient, I said they're lying.

But honestly, if Barbara hadn't been there filming it, I'm not sure that Issa wouldn't have been killed, even with me standing there. Having two Westerners observe, you would think would be enough to stop that assault. And having Barbara filming, you would think, are you crazy? Then the only reason that this story got any amplitude is that we did post it [on social media].

Things like this happen all the time. It's just that we were there that this particular episode got any notice at all. The IDF asked me to come in and they wanted me to know that they don't approve of this. And okay, glad to hear you don't approve of it. But these kids should never be put in this position. You know, it's humiliating to be occupied to start with, but also to have the judgment of an 18-year-old boy who has been fed, perhaps, on a lifetime of lies and hatred. It's a very volatile, humiliating experience.