Noureddine Jebnoun teaches at Georgetown University’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies in the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service.

Despite predictably low turnout, voters in Tunisia approved the heavily flawed referendum on a new constitution put forward by President Kais Saied on the one-year anniversary of his self-coup. This prosaic, sultanistic and quasi-legal constitution is set to become the highest law in the land, cementing the kind of one-man rule that Tunisians thought ended in 2011 with the popular revolution against longtime autocrat Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

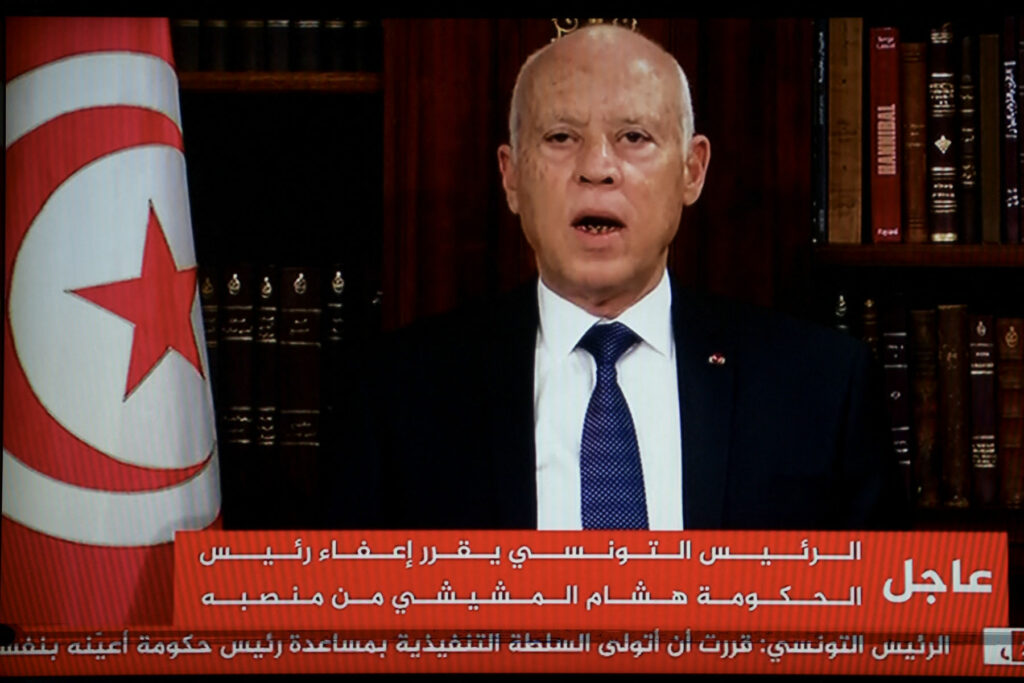

Only 2.8 million people came out to vote on July 25, out of 9.3 million Tunisians registered by the Independent High Authority for Elections, known as ISIE in its French acronym—which was hardly independent, as Saied granted himself sole powers to appoint its members this spring. The preliminary results of the constitutional referendum showed a voter turnout of just 30.5 percent. Nearly 2.6 million "yes" votes, representing 94.6 percent of those who cast ballots, sufficed to make the results binding in a plebiscite now marred by credible allegations of fraud. Yet with nearly 70 percent of eligible voters boycotting the referendum, Saied effectively failed to secure overwhelmingly popular support for his constitution, even as he claims it has won Tunisians' endorsement. "The masses that came out today across the country show the significance of this moment," he said in an address to his supporters in Tunis after polls closed.

Saied issued his first draft constitution on June 30, only to amend it on July 8, introducing 46 amendments to the original text, none of which checked the president's practically unlimited power. A weakened legislature and judiciary were both reduced to secondary functions, existing under the president's authority. According to Saied's former colleague, Sghair Zakraoui, a constitutional law professor, this tailored draft was "written surreptitiously and reflects Saied's ideas since he was a student," including a rhetorical preamble that fails to enact any basic constitutional principles. It fallaciously rewrites the country's history while erasing any references to Tunisia's first constitutional charter, the 1857 Fundamental Pact under the Ottoman Empire, as well as the 1959 constitution that followed Tunisia's independence from France and the 2014 post-authoritarian one.

This prosaic, sultanistic and quasi-legal constitution is set to become the highest law in the land, cementing the kind of one-man rule that Tunisians thought ended with the revolution against Ben Ali.

- Noureddine Jebnoun

Saied clearly embraced this reductionist approach in the draft constitution, while bestowing upon himself the imperious task to "correct the course of the revolution and even the course of history." These delusions of grandeur are palpable across the new constitution. Despite his claims to constitutional expertise, Saied in fact had minimal academic standing and no scholarly achievements as a minor law professor, when he failed to publish even one peer-reviewed article.

The new constitution reproduces verbatim a previous article introduced under Ben Ali's 2002 constitutional referendum that confers to the head of the state "judicial immunity in the exercise of his duties," even "after the presidential term for all acts executed as part of the office." It's immunity for life. And while Saied's charter duplicates almost the all of the articles on political rights and freedoms from the 2014 constitution, these rights will not be guaranteed in light of a weak judiciary constantly subjugated to the president's control and interference.

Much has been written on the role of this hollow text in constitutionalizing the authoritarianism that Tunisians thought was fully buried in 2014 with the celebration of a democratic constitution, imperfect as it was, that meant to diffuse power between the executive and legislature while guaranteeing the independence of the judiciary. The debate on the "constitutionality," or lack thereof, of the whole power-grabbing process that Saied triggered on July 25, 2021 has been mainly centered around the provisions of Article 80 of the 2014 constitution, regarding the "exceptional" measures the president could take "in the event of imminent danger threatening the nation's institutions or the security or independence of the country."

But it goes deeper than that. With his usurpation of power and use of "exceptional measures," culminating in this week's referendum, Saied has ruled Tunisia through a "state of exception." According to the Italian political philosopher Giorgio Agamben, invoking an emergency to dismiss the rule of law is grounded in a political rather than constitutional and legal framework—it "appears as the legal form of what cannot have legal form." The state of exception constitutes a "no-man's-land between public law and political fact," Agamben argued, and is "the preliminary condition for any definition of the relation that binds and, at the same time, abandons the living being to law."

Saied's new constitution is the codification of a permanent state of exception. Within his government, there are many proponents of this lawlessness, mainly Saied's defense minister, Imed Memmich, a former professor of law himself. Long before Saied's election in 2019, Memmich asserted in a co-authored paper published in 2014 by the Tunis office of the German foundation Friedrich Ebert Stiftung that Article 80 "enables the president to exercise a dictatorship of national salvation by undertaking all necessary measures to ensure the return to the normal course of the state's affairs." This "dictatorship of national salvation" is rooted in Jean-Jacques Rousseau's controversial conception of "sovereign dictatorship," advocating that "a Dictator could in some cases defend public freedom without ever being in a position to threaten it."

In other words, "sovereign" decisions have the upper hand over any law, including the constitutional order, and most importantly cannot be challenged. In the past year, Saied has embodied Rousseau's sovereign dictatorship by ruling through absolute presidential decrees immune from any form of appeal or oversight, while intimidating, criminalizing and prosecuting citizens for exercising their constitutional rights, including freedom of speech and assembly.

Yet despite Saied's authoritarian impulses, many Tunisians still support him. In the country's southern hinterland, I spoke this summer to Tunisians who continue to see him as a "man of moral integrity," as some put it, who rejects the mainstream political game and its parties and instead promises to fight corruption and improve the living standards of the poor. Citizens in these marginalized areas of the country are more consumed with dire economic and social issues—including poverty, regional inequality, unemployment, corruption, environmental degradation, and the lack of adequate access to health care and quality education—that continue to plague their lives on a daily basis. They consider as alien to their local struggle the political arm-wrestling in Tunis between the president and his opponents, mainly the Citizens Against the Coup initiative and the National Salvation Front, a coalition of several political parties and organizations, including Ennahda, the Islamist political party that dominated parliament before Saied dissolved it.

This deep apathy comes after a decade of dismally poor governance, when Tunisia's main political parties and actors failed to improve people's living standards while systematically resorting to neoliberal austerity policies and chaotic privatization schemes as the economy crumbled. The government's ineffectiveness in managing the COVID-19 pandemic during the country's worst wave in the spring of 2021 led to even more discontent and mistrust toward a system of politics and political elites seen as "disappointing, incompetent, self-serving and completely disconnected from bottom up dynamics in the country's margins," in the words of one Tunisian I interviewed.

Saied's new constitution is the codification of a permanent state of exception.

- Noureddine Jebnoun

The only thing that could now force Saied into any major concessions, or even lead to regime breakdown, is mass mobilization of the magnitude witnessed in 2010-11 against Ben Ali. Both the military and security forces would be forced to choose between mass repression and standing by Saied, or at least maintaining a neutral posture.

Saied's opponents contend that he relies extensively on the state's hard power—the coercive institutions of the security services and armed forces—to assert his personal authority while abruptly forcing through his own unconstitutional project. Although the Interior Ministry under Taoufik Charfeddine, Saied's loyal henchman, has played a key role in the regime's repression since July 25, 2021, its role reflects a decade of appeasement and temporizing by previous governments. They all utterly failed to implement structural security sector reform in a country where civilian decision-makers continue to deal with this realm as a terra incognita. Instead, civilian government officials cozied up to the security establishment while turning a blind eye to gross human rights violations under Ben Ali by turning the page on previous abuses and feigning amnesia.

It was thus easy for Saied and his acolytes to bring back the playbook of repression, with the same old infamous methods, that prevailed under Ben Ali, from police violence and mass arrests of activists to house arrest, kidnapping and torture. Ironically, in persecuting his opponents, Islamists chief among them, Saied is resorting to a flawed legal arsenal, including the sweeping 2015 law against terrorism and money laundering, which Ennahda and its allies were instrumental in drafting and passing.

The military, in contrast, which suffered from decades of marginalization as a peripheral state institution under Ben Ali, has seen its role and mission enhanced since 2011, while enjoying significant popular trust. However, the persistence of Saied's "exceptional measures" seems to be negatively impacting the image of the armed forces, as the presence of their top brass in many national security meetings in Carthage Palace created a perception of an institution that is in symbiosis with Saied's decisions. The photograph of members of the High Council of the Armed Forces sitting with their counterparts from the Interior Ministry when Saied evoked a state of emergency on July 25, 2021 was apparently instrumental to his uncontested power grab.

Throughout all the meetings that followed in the presidential palace with the top military brass over the past year, a new dynamic emerged with two kinds of partisans: loyalists and legalists. Although the loyalists are a minority, they seem to have the wind in their sails, because they are led by an officer who enjoys seniority in rank and has ascendancy over his peers given his close, nurtured relationship with Saied that goes back to their high school days. The legalists are more prone to keep the armed forces away from politics and seem invested in the process of modernizing and professionalizing the military as an institution.

Still, loyalty might conflate with legality as Saied capitalizes on his status as a democratically elected president to exploit his relationship with senior officers, by making more visits to and official statements in military facilities, intentionally projecting the image that the military is loyal to him. Many junior officers who have experienced an improvement in their social status and have benefited from better training in the post-2011 era are more appreciative of the opportunities offered since the revolution. Their support for Saied is less tangible and, among the rank and file, there does not appear to be a cohesive position or a monolithic attitude toward the president. The military's professional reputation seems to be the main concern of senior officers, as they are reluctant to jeopardize their future careers with the potential risk of exposure to eventual judicial prosecution if Saied drags them into acts of violence against protesters.

Tunisia's once-promising transition from authoritarianism is again stranded. Opposition elites must move beyond their debating salons in Tunis and reach out to different segments of society, especially in those marginalized areas beyond the coast, in order to connect with citizens who feel abandoned by them and to cultivate a cross-class commitment to democratic values rooted in the experiences, norms and practices of all Tunisians. The alternative is obvious: Saied, the new Brutus of Carthage, taking the country further down this painful path of de-democratization.