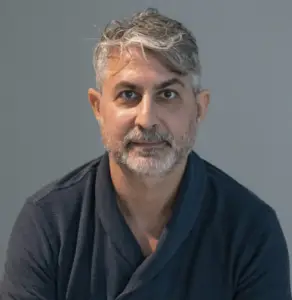

Egyptian journalist and political analyst and former Assistant Secretary-General of the Supreme Press Council - Egypt

Journalist Basma Mostafa was not the first journalist to be arrested by the police while carrying out her work, covering the murder of young Egyptian Owais al-Rawi by a police officer in Awamiya village, in Luxor, South of Egypt.

Mostafa's arrest came in the wake of anti-regime demonstrations that have swept Egypt since September 20. Basma Mostafa was also not the first journalist to be arrested because of her journalistic work; nor will she be the last under a regime that blatantly opposes freedom of the press and freedom of expression in general (the Prosecutor-General decided to release her while investigations continue).

Yet, Basma's arrest and disappearance for some time before she appeared at the Prosecutor's Office investigating her and ordering her detention on charges of spreading fake news and joining a terrorist group was the latest case.

It most epitomizes Egypt's ruling regime's subjugation of the free press. The press was a direct target of repression, confiscations, and closures since the very beginnings of General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi-led coup on July 3, 2013. No sooner had the coup taken place than many channels were shut, their programs stopped airing, and their presenters and even guests arrested inside the studios.

Basma Mustafa was by no means oblivious to the state of the freedom of the press in Egypt, which has been relegated to a dark zone under the Al-Sisi regime of regime. Egypt currently ranks 166th out of 180 countries in the world freedom of speech measures. Basma was such a brave professional that she overcame her fears. She has outstanding journalistic achievements under this repressive regime.

Basma uncovered the murder of 5 Egyptian citizens by the police because they had killed Italian student Giulio Regeni in a cover-up of the real murderer within the Egyptian intelligence services. She also wrote a piece about the Fairmont raped girl by a group of well-to-do boys who fled outside the country before the trial. A few weeks ago, she also reported on the murder, of Islam, a young Australian, by the police in Al-Munib, South of Cairo, in addition to many other daring investigative reports. Above all, Basma did not violate any laws. She traveled from Cairo to Luxor in broad daylight. She was on assignment for the electronic newspaper (Al-Manassa).

However, al-Rawi's murder was not eyed by authorities like other crimes, as it recalls the story of the murder of young Alexandrian Khaled Saeed as well as Sayed Bilal, who were among the triggers of the 25 January 2011 Revolution.

Egyptian Authorities fear that al-Rawi could trigger more protests if any media outlet gets to reach his family and reports the true and full story of his murder.

Attacks on and arrests of journalists seem to be routine matters in Egypt these days. According to the Arab Observatory for Media Freedom, over 70 correspondents and photographers of various Egyptian and foreign newspapers, channels, and news sites operating in Egypt are detained.

Many of them suffer from chronic or newly developed diseases while detained, requiring special treatments that prison authorities administration deny them. Thus their lives are threatened, similar to several political prisoners who died in their custody due to this medical negligence. The most recent case was that of Dr. Essam el-Erian, Vice Chairperson of the Freedom and Justice Party, and Dr. Amr Abu Khalil, brother of opposition journalist Haitham Abu Khalil. Amr Abu Khalil was mainly arrested as a punishment to his journalist brother.

There are many similar cases of relatives of Egyptian media professionals who spent unjustified periods in jail as a price for their kinship with those media professionals and as a form of moral pressure on their kin, who are journalists. Examples include the brothers of media figures Mohamed Nasser, Moataz Matar, Hisham Abdullah, Hamza Zobaa, Abdullah El-Sherif, etc.

The current regime's violations of freedom of the press are not limited to imprisoning journalists but are also include direct killing. This happened to ten journalists and photographers during the dispersal of the Rab'a sit-in in August 2013 and some ensuing protests during 2014 and 2015.

If police prosecutions were relatively limited to the persons suspected of having a relationship or sympathizing with the Islamist movement in the years following the military coup in 2013, this wave of prosecutions is more targeted at secular male and female journalists.

Oddly enough, authorities accuse these journalists of being part of a terrorist group in allusion to the Muslim Brotherhood, although they openly oppose the Muslim Brotherhood. This is the recent case of Basma Mustafa and, before her, Shaima Sami, Hisham Fouad, Husam Mu'nis, Israa Abdel Fattah, Sulafa Magdi, Ismail al-Iskandarani, etc.

Travel bans affected many Egyptian journalists as well. Many of them were placed on terrorist lists, which entails seizing their properties and passport denials. Yet, some of them are not affiliated with Islamic organizations.

Rather, they are their opponents, such as (leftist) Hisham Fouad and (Liberal) Mostafa Sakr, editor-in-chief of Al-Borsa newspaper, and (the Wafd Party member) Adel Sabry, Editor-in-chief of the Masr Al-Arabia website, who has recently been released. Bans on publishing articles affected many writers. The latest case in point was Amr Hashim Rabie, a political researcher, and journalist at Al-Ahram. Al-Masry Al-Youm newspaper didn't publish his article.

This was also the case of former military spokesman Muhammad Samir (as Veto newspaper wouldn't publish his article). The ban was issued under security directives, given that both articles criticize Senate elections (the second chamber of the Egyptian parliament).

In addition to these blatant violations, General el-Sisi's regime, which had exhibited, from the very start, a "monopolizing" vision of the media akin to that of former President Gamal Abdel Nasser, sought, early on, to achieve this vision through intelligence services.

The latter established companies with the aim of establishing satellite channels and news sites. Its most prominent model was the DMC Network. In like manner, it forced the owners of some other channels in various ways to abandon their channels and sell them to intelligence companies, such as businessmen Naguib Sawiris, Al-Sayyid al-Badawi, Mohamed al-Amin to name but a few.

This is to expand Egyptian intelligence services' domination over the media and become full or partial owners of over 70% of all private channels and websites. This media system will follow unified editorial plans and policies that only highlight the regime's wishes and conceal what it wishes to hide.

Meanwhile, there is mounting pressure on the offices of international channels and newspapers operating in Egypt to force them to adhere to the official version of the events announced by the Egyptian authorities without carrying out any independent investigations.

The repercussions of these pressures were apparent in the absence of international media coverage of the protests that swept many Egyptian villages and popular neighborhoods for over a week, starting from September 20.

In sum, the Egyptian press is experiencing its worst days, almost smothered to death. Will anyone come to its rescue?

***

Image from Basma Mostafa's public Facebook profile.